Using the ankle-brachial index to diagnose peripheral artery disease and assess cardiovascular risk

ABSTRACTThe ankle-brachial index is valuable for screening for peripheral artery disease in patients at risk and for diagnosing the disease in patients who present with lower-extremity symptoms that suggest it. The ankle-brachial index also predicts the risk of cardiovascular events, cerebrovascular events, and even death from any cause. Few other tests provide as much diagnostic accuracy and prognostic information at such low cost and risk.

KEY POINTS

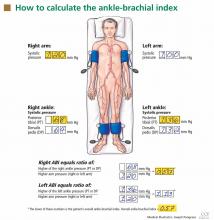

- The ankle-brachial index is the systolic pressure in the ankle (either the dorsalis pedis or the posterior tibial artery, whichever has the higher pressure) divided by the systolic pressure in the arm (either the left or right, whichever is higher). The lower of the two values obtained (left and right) is the patient’s overall ankle-brachial index.

- Most healthy adults have a value greater than 1.0. A value of less than 0.91 indicates significant peripheral artery disease, and a value lower than 0.40 at rest generally indicates severe disease. Values higher than 1.4 indicate stiffened, noncompressible arteries.

- Measuring the ankle-brachial index after exercise can uncover peripheral artery disease in patients with a normal resting ankle-brachial index.

In this article, we seek to convince you to measure the ankle-brachial index for any patient you suspect may have peripheral artery disease. This would include patients who are elderly, who smoke, or who have diabetes, regardless of whether or not they have symptoms. The ankle-brachial index is a simple test that involves taking the blood pressure in all four limbs using a hand-held Doppler device and then dividing the leg systolic pressure by the arm systolic pressure.

This simple test is both sensitive and specific for peripheral artery disease. It also gives a good assessment of cardiovascular risk. The downside: you or a member of your staff spends a few minutes doing it. Also, for patients without leg symptoms or abnormal findings on physical examination, you may not be paid for doing it.

Despite these limitations, the ankle-brachial index is a powerful clinical tool that deserves to be performed more often in primary care.

PERIPHERAL ARTERY DISEASE IS COMMON AND SERIOUS

Peripheral artery disease is important to detect, as it is common, it has serious consequences, and effective treatments are available. However, many patients with the disease do not have typical symptoms.

Peripheral artery disease affects up to 29% of people over age 70, depending on the population sampled.1,2 Its classic symptom is intermittent claudication, ie, leg pain with walking that improves with rest. However, most patients do not have intermittent claudication; they have atypical leg symptoms or no symptoms at all.2,3 While the risk factors for peripheral artery disease are similar to those for coronary artery disease, the factors most strongly associated with peripheral artery disease are older age, tobacco smoking, and diabetes mellitus.4 Blacks are twice as likely to have it compared with whites, even after adjusting for other cardiovascular risk factors.5

Untreated peripheral artery disease may have serious consequences, such as amputation, impaired functional capacity, poor quality of life, and depression.3,6,7 In addition, it is a strong marker of atherosclerotic burden and cardiovascular risk and has been recognized as a coronary risk equivalent. Patients with peripheral artery disease are at higher risk of death, myocardial infarction, stroke, and hospitalization, with event rates as high as 21% per year.8

Fortunately, simple therapies have been shown to prevent adverse cardiovascular events in peripheral artery disease, including antiplatelet drugs, statins, and angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors.9–11

THE ANKLE-BRACHIAL INDEX IS SENSITIVE AND SPECIFIC

The evaluation for possible peripheral artery disease should begin with the medical history, a cardiovascular review of systems, and a focused physical examination in which one should:

- Measure the blood pressure in both arms to assess for occult subclavian stenosis

- Auscultate for bruits over the carotid, abdominal, and femoral arteries

- Palpate the pulses in the lower extremities and the abdominal aorta

- Inspect the bare legs and feet for thinning of the skin, hair loss, thickening of the nails (which are nonspecific signs), and ulceration.

However, the physical examination has limited sensitivity and specificity for diagnosing peripheral artery disease. In general, the most reliable finding is the absence of a palpable posterior tibial artery pulse, which has been reported to have a specificity of 71% and a sensitivity of 91% for peripheral artery disease.12

The ankle-brachial index is the first-line test for both screening for peripheral artery disease and for diagnosing it. It is inexpensive and noninvasive to obtain and has a high sensitivity (79% to 95%) and specificity (95% to 96%) compared with angiography as the gold standard.13–18 It can be measured easily in the office, and every practitioner who cares for patients at risk of cardiovascular disease can be trained to measure it competently.

HOW TO MEASURE THE ANKLE-BRACHIAL INDEX

The ankle-brachial index is the ratio of the systolic pressure in the ankle to the systolic pressure in the arm. In healthy people, this ratio is typically greater than 1.0 or 1.1.

You can measure the ankle-brachial index in the office with a blood pressure cuff, sphygmomanometer, and handheld Doppler device. Alternatively, it can be measured in a noninvasive vascular laboratory as part of a more detailed examination that allows for assessment of blood pressures and waveforms (Doppler or pulse-volume recordings) at multiple segments along the limb. These more detailed vascular studies are generally reserved for patients with confirmed peripheral artery disease to locate the level and extent of blockage or for patients in whom lower-extremity revascularization is contemplated.

The use of a stethoscope to measure blood pressures for the ankle-brachial index has been studied in a few small series,19,20 but is thought to be less accurate than Doppler, especially in the setting of significant arterial occlusive disease. Because of this, it is recommended and assumed that a Doppler device be used to measure all blood pressures for the ankle-brachial index.

After the patient has been resting quietly for 5 to 10 minutes in the supine position, the systolic blood pressure is measured in both arms and in both ankles in the dorsalis pedis and posterior tibial arteries (Figure 1). The blood pressure cuff is placed about 1 inch above the antecubital fossa for the brachial pressure and about 2 inches above the medial malleolus for the ankle pressures. A clear arterial pulse signal should be heard using the Doppler probe before inflating the blood pressure cuff. The cuff is then inflated to at least 20 mm Hg above the point where the arterial Doppler sounds disappear and then slowly deflated until the Doppler sounds reappear. The blood pressure at which the Doppler signal of the arterial pulse reappears is the systolic pressure for that vessel.

The ankle-brachial index is calculated by dividing the higher of the two ankle systolic blood pressures in each leg by the higher of the two brachial systolic blood pressures. The higher of the two brachial pressures is used as the denominator to account for the possibility of subclavian artery stenosis, which can decrease the blood pressure in the upper extremity. The ankle-brachial index is calculated for each leg, and the lower value is the patient’s overall ankle-brachial index. An abnormal value in either leg indicates peripheral artery disease.

While other ways of calculating the ankle-brachial index have been proposed, such as averaging the two pressures at each ankle or reporting the lower of the two ankle pressures, these methods are not standard for use in clinical practice.

Similarly, the use of oscillometric blood pressure devices has been proposed, which would eliminate the need for a Doppler device and personnel trained in its use. However, results of validation studies of oscillometric measurement of the ankle-brachial index have been inconsistent, likely because the devices were designed for measuring blood pressure in nonobstructed arms, not the legs, and especially not diseased legs.21–25 In general, oscillometric devices tend to overestimate ankle pressure, giving a falsely high ankle-brachial index in patients with moderate to severe peripheral artery disease.21 Their utility in screening for peripheral artery disease has not been evaluated in broad, population-based studies. Efforts to develop and validate new oscillometric devices for diagnosing peripheral artery disease are ongoing.