Tender Nodule on the Umbilicus

THE DIAGNOSIS: Villar Nodule

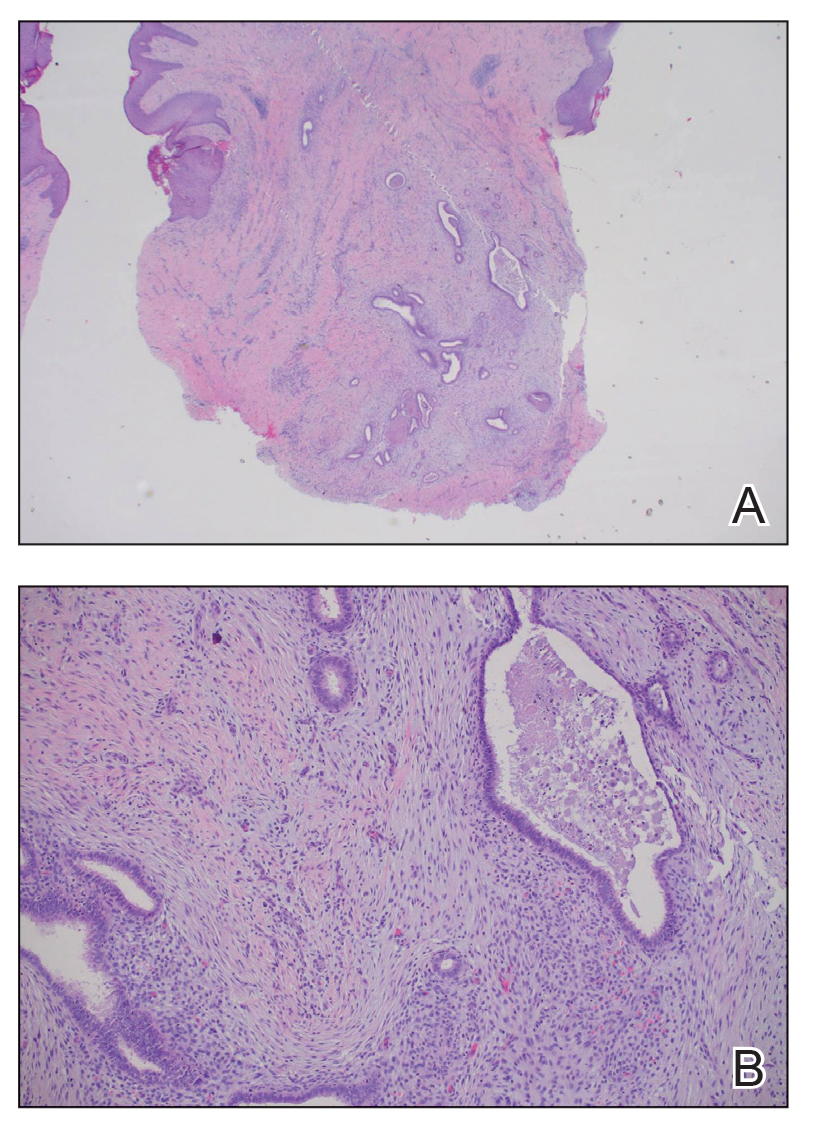

The biopsy revealed features consistent with cutaneous endometriosis in the setting of a painful, tender, multilobulated nodule with a cyclical bleeding pattern (Figure 1). The bleeding pattern of the nodule during menses and lack of surgical history supported the diagnosis of primary cutaneous endometriosis in our patient. She was diagnosed with endometriosis by gynecology, and her primary care physician started her on an oral contraceptive based on this diagnosis. She also was referred to gynecology and plastic surgery for a joint surgical consultation to remove the nodule. She initially decided to do a trial of the oral contraceptive but subsequently underwent umbilical endometrioma excision with neo-umbilicus creation with no evidence of recurrence.

Primary cutaneous endometriosis should be considered in young females who present with tender umbilical nodules. Endometriosis refers to the presence of an endometriumlike epithelium outside the endometrium and myometrium.1 The condition affects 10% to 15% of reproductive-aged (ie, 18-49 years) women in the United States and typically involves tissues within the pelvis, such as the ovaries, pouch of Douglas, or pelvic ligaments.2 Cutaneous endometriosis is the growth of endometrial tissue in the skin and is rare, accounting for less than 5.5% of cases of extrapelvic endometriosis worldwide, affecting primarily the umbilicus, abdominal wall, and vulva.3,4

The 2 main types of cutaneous endometriosis are primary (spontaneous) and secondary. Primary lesions develop in patients without prior surgical history, and secondary lesions occur within previous surgical incision sites, often scars from cesarean delivery.5 Less than 30% of cases of cutaneous endometriosis are primary disease.6 Primary cutaneous endometriosis of the umbilicus, known as Villar nodule, was first described in 1886.3,7 Up to 40% of patients with extrapelvic endometriosis worldwide presented with Villar nodules in a systematic literature review.6 The prevalence of these nodules is unknown, but the incidence is less than 1% of cases of extragenital endometriosis.4

There are 2 leading theories of primary cutaneous endometriosis pathogenesis. The first is the transportation theory, in which endometrial cells are transported outside the uterus via the lymphatic system.8 The second is the metaplasia theory, which proposed that endometrial cells develop in the coelomic mesothelium in the presence of high estrogen levels.8,9

Secondary cutaneous endometriosis, also known as scar endometriosis, is suspected to be caused by an iatrogenic implantation of endometrial cells at the scar of a prior surgical site.9 Although our patient had an existing umbilicus scar from a piercing, it was improbable for that to have been the nidus, as the keloid scar was superficial and did not have contact with the abdominal cavity for iatrogenic implantation. Clinical diagnosis for secondary cutaneous endometriosis often is made based on a triad of features: a nonmalignant abdominal mass, recurring pain and bleeding of the lesion with menses, and prior history of abdominal surgery.9,10 On clinical examination, these features typically manifest as a palpable subcutaneous mass that is black, blue, brown, or red. Often, the lesions enlarge and bleed during the menstrual cycle, causing pain, tenderness, or pruritus.3 Dermoscopic features of secondary cutaneous endometriosis are erythematous umbilical nodules with a homogeneous vascular pattern that appears red with a brownish hue (Figure 2).9,11 Dermoscopic features may vary with the hormone cycle; for example, the follicular phase (correlating with day 7 of menses) demonstrates polypoid projections, erythematous violaceous color, dark-brown spots, and active bleeding of the lesion.12 Clinical and dermoscopic examination are useful tools in this diagnosis.

Imaging such as ultrasonography, computed tomography, or magnetic resonance imaging may be useful in identifying abdominal endometriomas.8,13,14 Pelvic involvement of endometriosis was found in approximately 15% of patients in a case series,4 with concurrent primary umbilical endometriosis. Imaging studies may assist evaluation for fistula formation, presence of malignancies, and the extent of endometriosis within the abdominal cavity.

Histopathology is key to confirming cutaneous endometriosis and shows multiple bland-appearing glands of varying sizes with loose, concentric, edematous, or fibromyxoid stroma (Figure 1).3 Red blood cells sometimes are found with hemosiderin within the stroma. Immunohistochemical staining with estrogen receptors may aid in identifying the endometriumlike epithelial cells.13

Standard treatment involves surgical excision with 1-cm margins and umbilical preservation, which results in a recurrence rate of less than 10%.4,10 Medical therapy, such as aromatase inhibitors, progestogens, antiprogestogens, combined oral contraceptives, or gonadotropin-releasing hormone agonists or antagonists may help manage pain or reduce the size of the nodule.4,15 Simple observation also is a potential course for patients who decline treatment options.

Differential diagnoses include lobular capillary hemangioma, also known as pyogenic granuloma; Sister Mary Joseph nodule; umbilical hernia; and dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans. Lobular capillary hemangiomas commonly are acquired benign vascular proliferations of the skin that are friable and tend to ulcerate.16 These lesions typically grow rapidly and often are located on the face, lips, mucosae, and fingers. Histopathologic examination may show an exophytic lesion with lobules of proliferating capillaries within an edematous matrix, superficial ulceration, and an epithelial collarette.17 Treatment includes surgical excision, cauterization, laser treatments, sclerotherapy, injectable medications, and topical medications, but recurrence is possible with any of these interventions.18

Cutaneous metastasis of an internal solid organ cancer, commonly known as a Sister Mary Joseph nodule, typically manifests as an erythematous, irregularly shaped nodule that may protrude from the umbilicus.14 Gastrointestinal symptoms such as change in bowel habits or obstructive symptoms in the setting of a progressive malignancy are common.14 Clinical features include a firm fixed lesion, oozing, and ulceration.19 On dermoscopy, polymorphous vascular patterns, milky red structureless areas, and white lines typically are present.11 Although dermoscopic features may differentiate this entity from cutaneous endometriosis, tissue sampling and histologic examination are crucial diagnostic tools to identify malignant vs benign lesions.

An umbilical hernia is a protrusion of omentum, bowel, or other intra-abdominal organs in an abdominal wall defect. Clinical presentation includes a soft protrusion that may be reduced on palpation if nonstrangulated.20 Treatment includes watchful waiting or surgical repair. The reducibility and presence of an abdominal wall defect may point to this diagnosis. Imaging also may aid in the diagnosis if the history and physical examination are unclear.

Dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans is a slow-developing, low- to intermediate-grade, soft-tissue sarcoma that occurs in less than 0.1% of all cancers in the United States.21 Lesions often manifest as small, firm, slow-growing, painless, flesh-colored dermal plaques; subcutaneous thickening; or atrophic nonprotuberant lesions typically involving the trunk.21 Histopathologically, they are composed of uniform spindle-cell proliferation growing in a storiform pattern and subcutaneous fat trapping that has strong and diffuse CD34 immunoreactivity.21,22 Pathologic examination typically distinguishes this diagnosis from cutaneous endometriosis. Treatment includes tumor resection that may or may not involve radiotherapy and targeted therapy, as recurrence and metastases are possible.

Primary cutaneous endometriosis is a rare but important diagnosis for dermatologists to consider when evaluating umbilical nodules. Clinical features may include bleeding masses during menses in females of reproductive age. Dermoscopic examination aids in workup, and histopathologic testing can confirm the diagnosis and rule out malignancies. Surgical excision is the treatment of choice with a low rate of recurrence.