Management of Isolated Greater Tuberosity Fractures: A Systematic Review

As isolated fractures of the greater tuberosity present a therapeutic challenge, we systematically reviewed all studies of greater tuberosity fracture management. Inclusion criteria were level I to IV evidence and 2-year follow-up. Thirteen studies and 429 shoulders were included in our analyses, which compared 3 paired groups: treatment type (nonoperative vs operative), fracture displacement amount (<5 mm vs >5 mm), and surgery type (open vs arthroscopic).

Concomitant anterior glenohumeral instability was documented in 28.1% of patients and was significantly more common in displaced vs nondisplaced fractures (44.3% vs 14.5%; P < .01). Compared with nonoperative patients, operative patients had significantly fewer radiographic losses of reduction (48.6% vs 5.2%; P < .01) but increased shoulder stiffness (0.0% vs 5.7%; P < .01). Heterotopic ossification was more common in displaced vs nondisplaced fractures (7.5% vs 0.0%; P < .01). There were no significant differences in outcome between arthroscopic and open surgery, but with screw fixation (vs suture constructs) there were significantly fewer cases of stiffness (0% vs 12.0%; P < .01) and reoperation (0% vs 8.0%; P = .051).

Surgery for displaced fractures is associated with high patient satisfaction and low rates of complications and reoperations, regardless of technique and fixation mode.

Take-Home Points

- Fractures of the greater tuberosity are often mismanaged.

- Comprehension of greater tuberosity fractures involves classification into nonoperative and operative treatment, displacement >5mm or <5 mm, and open vs arthroscopic surgery.

- Nearly a third of patients may suffer concomitant anterior glenohumeral instability.

- Stiffness is the most common postoperative complication.

- Surgery is associated with high patient satisfaction and low rates of complications and reoperations.

Although proximal humerus fractures are common in the elderly, isolated fractures of the greater tuberosity occur less often. Management depends on several factors, including fracture pattern and displacement.1,2 Nondisplaced fractures are often successfully managed with sling immobilization and early range of motion.3,4 Although surgical intervention improves outcomes in displaced greater tuberosity fractures, the ideal surgical treatment is less clear.5

Displaced greater tuberosity fractures may require surgery for prevention of subacromial impingement and range-of-motion deficits.2 Superior fracture displacement results in decreased shoulder abduction, and posterior displacement can limit external rotation.6 Although the greater tuberosity can displace in any direction, posterosuperior displacement has the worst outcomes.1 The exact surgery-warranting displacement amount ranges from 3 mm to 10 mm but is yet to be clearly elucidated.5,6 Less displacement is tolerated by young overhead athletes, and more displacement by older less active patients.5,7,8 Surgical options for isolated greater tuberosity fractures include fragment excision, open reduction and internal fixation (ORIF), closed reduction with percutaneous fixation, and arthroscopically assisted reduction with internal fixation.3,9,10

We conducted a study to determine the management patterns for isolated greater tuberosity fractures. We hypothesized that greater tuberosity fractures displaced <5 mm may be managed nonoperatively and that greater tuberosity fractures displaced >5 mm require surgical fixation.

Methods

Search Strategy

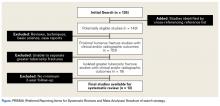

We performed this systematic review according to the PRISMA (Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses) checklist11 and registered it (CRD42014010691) with the PROSPERO international prospective register of systematic reviews. Literature searches using the PubMed/Medline database and the Cochrane Central Register of Clinical Trials were completed in August 2014. There were no date or year restrictions. Key words were used to capture all English- language studies with level I to IV evidence (Oxford Centre for Evidence-Based Medicine) and reported clinical or radiographic outcomes. Initial exclusion criteria were cadaveric, biomechanical, histologic, and kinematic results. An electronic search algorithm with key words and a series of NOT phrases was designed to match our exclusion criteria:

((((((((((((((((((((((((((((((((((((((((((((((((((greater[Title/Abstract]) AND tuberosity [Title/Abstract] OR tubercle [Title/Abstract]) AND fracture[Title/Abstract]) AND proximal[Title/Abstract] AND (English[lang]))) NOT intramedullary[Title] AND (English[lang]))) NOT nonunion[Title] AND (English[lang]))) NOT malunion[Title] AND (English[lang]))) NOT biomechanical[Title/Abstract] AND (English[lang]))) NOT cadaveric[Title/Abstract] AND (English[lang]))) NOT cadaver[Title/Abstract] AND (English[lang]))) NOT ((basic[Title/Abstract]) AND science[Title/Abstract] AND (English[lang])) AND (English[lang]))) NOT revision[Title] AND (English[lang]))) NOT pediatric[Title] AND (English[lang]))) NOT physeal[Title] AND (English[lang]))) NOT children[Title] AND (English[lang]))) NOT instability[Title] AND (English[lang]))) NOT imaging[Title])) NOT salter[Title])) NOT physis[Title])) NOT shaft[Title])) NOT distal[Title])) NOT clavicle[Title])) NOT scapula[Title])) NOT ((diaphysis[Title]) AND diaphyseal[Title]))) NOT infection[Title])) NOT laboratory[Title/Abstract])) NOT metastatic[Title/Abstract])) NOT (((((((malignancy[Title/Abstract]) OR malignant[Title/Abstract]) OR tumor[Title/Abstract]) OR oncologic[Title/Abstract]) OR cyst[Title/Abstract]) OR aneurysmal[Title/Abstract]) OR unicameral[Title/Abstract]).