Infectious Sacroiliitis in a Patient With a History of IV Drug Use

Case

A 29-year-old man presented to the ED with a 3-day history of constant left-sided low back pain that radiated to his left buttock and groin. The patient stated the pain worsened with movement, making it difficult for him to walk. He reported lifting heavy boxes at work, but denied any trauma. The patient also denied recent fevers, chills, chest pain, dyspnea, abdominal pain, urinary or fecal incontinence, weakness, numbness, or saddle anesthesia. Regarding his medical history, he had an appendectomy as a child, but reported no other surgeries or medical issues. His social history was significant for narcotic and inhalant use and daily tobacco use. The patient also reported taking heroin intravenously (IV) 6 months prior.

Vital signs at presentation were: heart rate (HR), 92 beats/min; respiratory rate, 15 breaths/min; blood pressure, 118/80 mm Hg; and temperature, 98.2°F. Oxygen saturation was 98% on room air.

The patient was a well-developed young man in no apparent distress. Dermatological examination showed bilateral track marks in the antecubital fossa. The musculoskeletal (MSK) examination demonstrated left gluteal tenderness to palpation and decreased active and passive range of motion of the left hip, especially with internal rotation and flexion. He had no midline tenderness, and the lower extremities had normal pulses and no motor or sensory deficits.

The patient’s pain improved with IV fluids, diazepam, and ketorolac, and he was able to ambulate with assistance. He was clinically diagnosed with sciatica, and discharged home with prescriptions for diazepam and ibuprofen. He was also instructed to follow-up with an orthopedist within 7 days from discharge.

The patient returned to the ED the following day with similar complaints of unabating left-sided pain and difficulty ambulating. His vital signs were notable for an elevated HR of 106 beats/min. Physical examination findings were unchanged from his presentation the previous day, and an X-ray of the lumbar spine showed no abnormalities.

After receiving IV analgesics, the patient’s pain improved and his tachycardia resolved. He was discharged home with instructions to continue taking diazepam, and was also given prescriptions for prednisone and oxycodone/acetaminophen. He was instructed to follow-up with an orthopedist within 24 hours.

Over the next 9 days, the patient was seen twice by an orthopedist, who ordered imaging of the lumbar spine, including a repeat X-ray and contrast-enhanced magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), both of which were unremarkable. The patient completed the prescribed course of diclofenac, oxycodone/acetaminophen, and prednisone, but experienced only minimal pain relief. The orthopedist prescribed the diclofenac to supplement the medication regimen that he was already on.

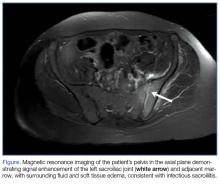

At the second follow-up visit, the orthopedist ordered an MRI of the patient’s left hip, which demonstrated inflammation of the left sacroiliac joint (SIJ) with effusion, and a 1-cm by 1-cm collection adjacent to the left psoas muscle; these findings were concerning for septic arthritis (Figure). Based on the MRI study, a computed tomography (CT)-guided arthrocentesis of the left SIJ was performed by an interventional radiologist.

Following the arthrocentesis, the orthopedist referred the patient to the ED. At this presentation, the emergency physician (EP) ordered blood cultures, blood work, urinalysis, and a urinary toxicology screen, and started the patient on IV ceftriaxone and vancomycin. The laboratory studies were significant for the following elevated inflammatory markers: erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR), 19 mm/h; C-reactive protein (CRP), 2.45 mg/L; white blood cell count (WBC), 13.6 K/uL with normal differential; and lactate level, 2.6 mg/dL. The toxicology screen was positive for opioids. The basic metabolic panel, chest X-ray, and urinalysis were all unremarkable. An electrocardiogram showed sinus tachycardia.

The patient was admitted to the hospital, and infectious disease services was contacted. While awaiting transport to the inpatient floor, the patient admitted to IV drug use 4 weeks prior to his initial presentation—not the 6 months he initially reported at the first ED visit.

The blood cultures grew Candida parapsilosis, and culture from the SIJ arthrocentesis grew Pseudomonas aeruginosa. The infectious disease physician switched the patient’s antibiotic therapy to IV cefepime and fluconazole. The patient also was seen by an orthopedist, who determined that no surgical intervention was required.

Follow-up laboratory studies showed inflammatory markers peaking at the following levels: ESR, 36 mm/h; CRP, 4.84 mg/L; and WBC, 32.1 K/uL with 90% neutrophils. These markers normalized throughout his hospital stay. The patient was also tested for hepatitis and human immunodeficiency virus, both of which were negative. A transesophageal echocardiogram showed no obvious masses or vegetations.

The patient had an uncomplicated hospital course, and was discharged home on hospital day 6 with a 4-week prescription of oral fluconazole and levofloxacin, and instructed to follow-up with both infectious disease and the orthopedist. To address his history of IV drug use, he also was given follow-up with pain management.

One month later, the patient returned a fourth time to the ED for evaluation of bilateral lower extremity pain and swelling. He stated that he had been mostly bed-bound at home since his discharge from the hospital due to continued pain with weight-bearing.

The patient’s vital signs were normal. The EP ordered a duplex ultrasound study, which showed extensive bilateral lower extremity deep vein thrombosis. He was started on subcutaneous therapeutic enoxaparin and admitted to the inpatient hospital. During admission, a left lower lobe pulmonary artery embolism was found on chest CT angiography, though he had no cardiac or respiratory symptoms. He was discharged home with a 3-month prescription for oral rivaroxaban.

At a 4-month follow-up visit, the patient reported minimal residual disability after completing the course of treatment. During the follow-up, the patient denied using IV heroin; he was referred to a pain management specialist, who placed the patient on methadone.