Managing aneurysmal subarachnoid hemorrhage: It takes a team

ABSTRACTPatients with aneurysmal subarachnoid hemorrhage are at high risk of complications, including rebleeding, delayed cerebral ischemia, cerebral infarction, and death. This review presents a practical approach for managing this condition and its complications.

KEY POINTS

- The key symptom is the abrupt onset of severe headache, commonly described as “the worst headache of my life.

- Computed tomography without contrast should be done promptly when this condition is suspected.

- Outcomes are improved when patients are managed in a high-volume center with a specialized neurointensive care unit and access to an interdisciplinary team.

- Early aneurysm repair by surgical clipping or endovascular coiling is considered the standard of care and is the best strategy to reduce the risk of rebleeding.

- Medical and neurologic complications are extremely common and include hydrocephalus, increased intracranial pressure, seizures, delayed cerebral ischemia, hyponatremia, hypovolemia, and cardiac and pulmonary abnormalities.

TREATING DELAYED CEREBRAL ISCHEMIA

Hemodynamic augmentation

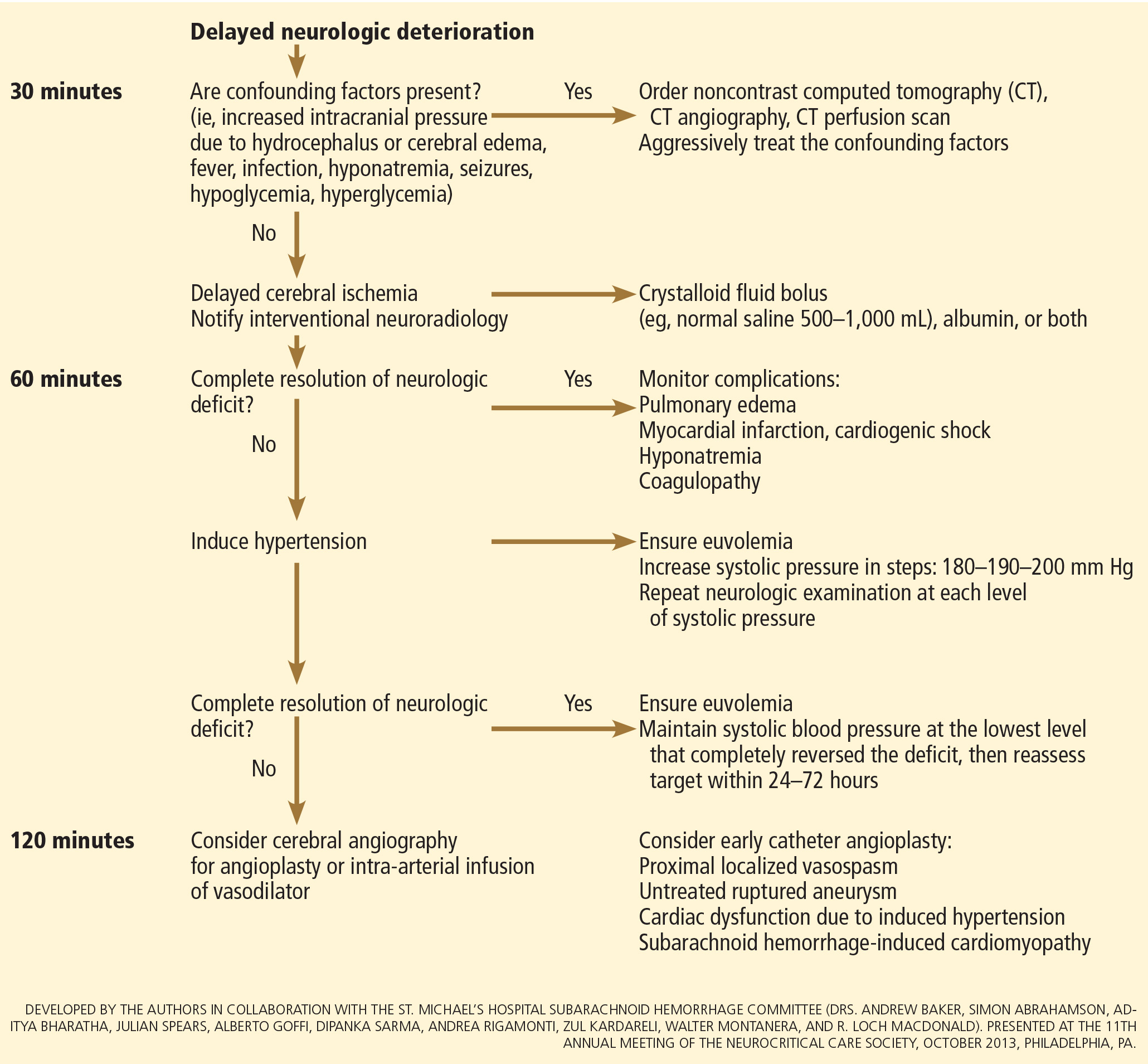

In patients with neurologic deterioration due to delayed cerebral ischemia, hemodynamic augmentation is the cornerstone of treatment. This is done according to a protocol, started early, involving specific physiologic goals, clinical improvement, and escalation to invasive therapies in a timely fashion in patients at high risk of further neurologic insult (Figure 5).

The physiologic goal is to increase the delivery of oxygen and glucose to the ischemic brain. Hypertension seems to be the most effective component of hemodynamic augmentation regardless of volume status, increasing cerebral blood flow and brain tissue oxygenation, with reversal of delayed cerebral ischemic symptoms in up to two-thirds of treated patients.74,75 However, this information comes from very small studies, with no randomized trials of induced hypertension available.

The effect of a normal saline fluid bolus in patients suspected of having delayed cerebral ischemia has been shown to increase cerebral blood flow in areas of cerebral ischemia.74 If volume augmentation fails to improve the neurologic status, the next step is to artificially induce hypertension using vasopressors. The blood pressure target should be based on clinical improvement. A stepwise approach is reasonable in this situation, and the lowest level of blood pressure at which there is a complete reversal of the new focal neurologic deficit should be maintained.3,29

Inotropic agents such as dobutamine or milrinone can be considered as alternatives in patients who have new neurologic deficits that are refractory to fluid boluses and vasopressors, or in a setting of subarachnoid hemorrhage-induced cardiomyopathy.76,77

Once the neurologic deficit is reversed by hemodynamic augmentation, the blood pressure should be maintained for 48 to 72 hours at the level that reversed the deficit completely, carefully reassessed thereafter, and the patient weaned slowly. Unruptured unsecured aneurysms should not prevent blood pressure augmentation in a setting of delayed cerebral ischemia if the culprit aneurysm is treated.3,32 If the ruptured aneurysm has not been secured, careful blood pressure augmentation can be attempted, keeping in mind that hypertension (> 160/95 mm Hg) is a risk factor for fatal aneurysm rupture.

Endovascular management of delayed cerebral ischemia

When medical augmentation fails to completely reverse the neurologic deficits, endovascular treatment can be considered. Although patients treated early in the course of delayed cerebral ischemia have better neurologic recovery, prophylactic endovascular treatment in asymptomatic patients, even if angiographic signs of spasm are present, does not improve clinical outcomes and carries the risk of fatal arterial rupture.78

SYSTEMIC COMPLICATIONS

Hyponatremia and hypovolemia

Aneurysmal subarachnoid hemorrhage is commonly associated with abnormalities of fluid balance and electrolyte derangements. Hyponatremia (serum sodium < 135 mmol/L) occurs in 30% to 50% of patients, while the rate of hypovolemia (decreased circulating blood volume) ranges from 17% to 30%.79 Both can negatively affect long-term outcomes.80,81

Decreased circulating blood volume is a well-described contributor to delayed cerebral ischemia and cerebral infarction after aneurysmal subarachnoid hemorrhage.80–82 Clinical variables such as heart rate, blood pressure, fluid balance, and serum sodium concentration are usually the cornerstones of intravascular volume status assessment. However, these variables correlate poorly with measured circulating blood volumes in those with aneurysmal subarachnoid hemorrhage.83,84

The mechanisms responsible for the development of hyponatremia and hypovolemia after aneurysmal subarachnoid hemorrhage are not completely understood. Several factors have been described and may contribute to the increased natriuresis and, hence, to a reduction in circulating blood volume: increased circulating natriuretic peptide concentrations,85–87 sympathetic nervous system hyperactivation,88 and hyperreninemic hypo-

aldosteronism syndrome.89,90

Lastly, the cerebral salt wasting syndrome, described in the 1950s,91 was thought to be a key mechanism in the development of hyponatremia and hypovolemia after aneurysmal subarachnoid hemorrhage. In contrast to the syndrome of inappropriate antidiuretic hormone, which is characterized by hyponatremia with a normal or slightly elevated intravascular volume, the characteristic feature of cerebral salt wasting syndrome is the development of hyponatremia in a setting of intravascular volume depletion.92 In critically ill neurologic and neurosurgical patients, this differential diagnosis is very difficult, especially in those with aneurysmal subarachnoid hemorrhage in whom the clinical assessment of fluid status is not reliable. These two syndromes might coexist and contribute to the development of hyponatremia after aneurysmal subarachnoid hemorrhage.92,93

Hoff et al83,84 prospectively compared the clinical assessment of fluid status by critical and intermediate care nurses and direct measurements of blood volume using pulse dye densitometry. The clinical assessment failed to accurately assess patients’ volume status. Using the same technique to measure circulating blood volume, this group showed that calculation of fluid balance does not provide adequate assessment of fluid status.83,84

Hemodynamic monitoring tools can help guide fluid replacement in this population. Mutoh et al94 randomized 160 patients within 24 hours of hemorrhage to receive early goal-directed fluid therapy (ie, preload volume and cardiac output monitored by transpulmonary thermodilution) vs standard therapy (ie, fluid balance or central venous pressure). Overall, no difference was found in the rates of delayed cerebral ischemia (33% vs 42%; P = .33) or favorable outcome (67% vs 57%; P = .22). However, in the subgroup of poor-grade patients (WFNS score 4 or 5), early goal-directed therapy was associated with a lower rate of delayed cerebral ischemia (5% vs 14%; P = .036) and with better functional outcomes at 3 months (52% vs 36%; P = .026).

Fluid restriction to treat hyponatremia in aneurysmal subarachnoid hemorrhage is no longer recommended because of the increased risk of cerebral infarction due to hypovolemic hypoperfusion.82

Prophylactic use of mineralocorticoids (eg, fludrocortisone, hydrocortisone) has been shown to limit natriuresis, hyponatremia, and the amount of fluid required to maintain euvolemia.95,96 Higher rates of hypokalemia and hyperglycemia, which can be easily treated, are the most common complications associated with this approach. Additionally, hypertonic saline (eg, 3% saline) can be used to correct hyponatremia in a setting of aneurysmal subarachnoid hemorrhage.79

Cardiac complications

Cardiac complications after subarachnoid hemorrhage are most likely related to sympathetic hyperactivity and catecholamine-induced myocyte dysfunction. The pathophysiology is complex, but cardiac complications have a significant negative impact on long-term outcome in these patients.97

Electrocardiographic changes and positive cardiac enzymes associated with aneurysmal subarachnoid hemorrhage have been extensively reported. More recently, data from studies of two-dimensional echocardiography have shown that subarachnoid hemorrhage can also be associated with significant wall-motion abnormalities and even overt cardiogenic shock.98–100

There is no specific curative therapy; the treatment is mainly supportive. Vasopressors and inotropes may be used for hemodynamic augmentation.

Pulmonary complications

Pulmonary complications occur in 20% to 30% of all aneurysmal subarachnoid hemorrhage patients and are associated with a higher risk of delayed cerebral ischemia and death. Common pulmonary complications in this population are mild acute respiratory distress syndrome (27%), hospital-acquired pneumonia (9%), cardiogenic pulmonary edema (8%), aspiration pneumonia (6%), neurogenic pulmonary edema (2%), and pulmonary embolism (1%).101–103

SUPPORTIVE CARE

Hyperthermia, hyperglycemia, and liberal use of transfusions have all been associated with longer stays in the intensive care unit and hospital, poorer neurologic outcomes, and higher mortality rates in patients with acute brain injury.104 Noninfectious fever is the most common systemic complication after subarachnoid hemorrhage.

Antipyretic drugs such as acetaminophen and ibuprofen are not very effective in reducing fever in the subarachnoid hemorrhage population, but should still be used as first-line therapy. The use of surface and intravascular devices can be considered when fevers do not respond to nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs.

Although no prospective randomized trial has addressed the impact of induced normothermia on long-term outcome and mortality in aneurysmal subarachnoid hemorrhage patients, fever control has been shown to reduce cerebral metabolic distress, irrespective of intracranial pressure.105 Maintenance of normothermia (< 37.5°C) seems reasonable, especially in aneurysmal subarachnoid hemorrhage patients at risk of or with active delayed cerebral ischemia.106

Current guidelines3,32,69 strongly recommend avoiding hypoglycemia, defined as a serum glucose level less than 80 mg/dL, but suggest keeping the blood sugar level below 180 or 200 mg/dL.

At the moment, there is no clear threshold for transfusion in patients with aneurysmal subarachnoid hemorrhage. Current guidelines suggest keeping hemoglobin levels between 8 and 10 g/dL.3

Preventing venous thromboembolism

The incidence of venous thromboembolism after aneurysmal subarachnoid hemorrhage varies widely, from 1.5% to 18%.107 Active surveillance with venous Doppler ultrasonography has found asymptomatic deep vein thrombosis in up to 3.4% of poor-grade aneurysmal subarachnoid hemorrhage patients receiving pharmacologic thromboprophylaxis.108

In a retrospective study of 170 patients, our group showed that giving drugs to prevent venous thromboembolism (unfractionated heparin 5,000 IU subcutaneously every 12 hours or dalteparin 5,000 IU subcutaneously daily), starting within 24 hours of aneurysm treatment, could be safe.109 Fifty-eight percent of these patients had an external ventricular drain in place. One patient developed a major cerebral hemorrhagic complication and died while on unfractionated heparin; however, the patient was also on dual antiplatelet therapy with aspirin and clopidogrel.109

Current guidelines suggest that intermittent compression devices be applied in all patients before aneurysm treatment. Pharmacologic thromboprophylaxis with a heparinoid can be started 12 to 24 hours after aneurysm treatment.3,109

A TEAM APPROACH

Patients with subarachnoid hemorrhage need integrated care from different medical and nursing specialties. The best outcomes are achieved by systems that can focus as a team on the collective goal of quick intervention to secure the aneurysm, followed by measures to minimize secondary brain injury.

The modern concept of cerebral monitoring in a setting of subarachnoid hemorrhage should focus on brain perfusion rather than vascular diameter. Although the search continues for new diagnostic, prognostic, and therapeutic tools, there is no “silver bullet” that will help all patients. Instead, it is the systematic integration and application of many small advances that will ultimately lead to better outcomes.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

This work was supported by research funding provided by the Bitove Foundation, which has been supportive of our clinical and research work for several years.