Managing aneurysmal subarachnoid hemorrhage: It takes a team

ABSTRACTPatients with aneurysmal subarachnoid hemorrhage are at high risk of complications, including rebleeding, delayed cerebral ischemia, cerebral infarction, and death. This review presents a practical approach for managing this condition and its complications.

KEY POINTS

- The key symptom is the abrupt onset of severe headache, commonly described as “the worst headache of my life.

- Computed tomography without contrast should be done promptly when this condition is suspected.

- Outcomes are improved when patients are managed in a high-volume center with a specialized neurointensive care unit and access to an interdisciplinary team.

- Early aneurysm repair by surgical clipping or endovascular coiling is considered the standard of care and is the best strategy to reduce the risk of rebleeding.

- Medical and neurologic complications are extremely common and include hydrocephalus, increased intracranial pressure, seizures, delayed cerebral ischemia, hyponatremia, hypovolemia, and cardiac and pulmonary abnormalities.

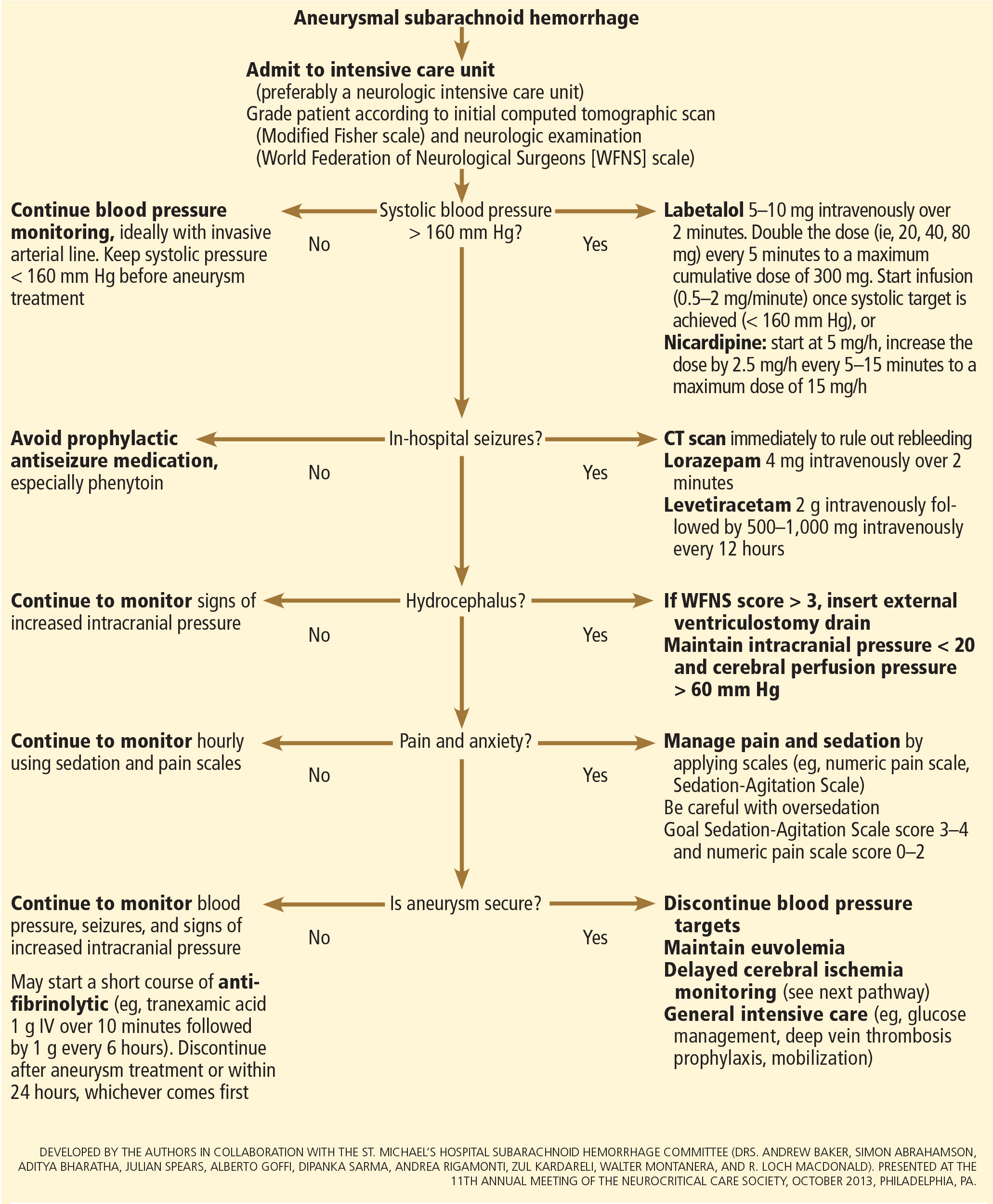

INITIAL MANAGEMENT

After aneurysmal subarachnoid hemorrhage is diagnosed, the initial management (Figure 2) includes appropriate medical prevention of rebleeding (which includes supportive care, blood pressure management, and, perhaps, the early use of a short course of an antifibrinolytic drug) and early transfer to a high-volume center for securing the aneurysm. The reported incidence of rebleeding varies from 5% to 22% in the first 72 hours. “Ultra-early” rebleeding (within 24 hours of hemorrhage) has been reported, with an incidence as high as 15% and a fatality rate around 70%. Patients with poor-grade aneurysmal subarachnoid hemorrhage, larger aneurysms, and “sentinel bleeds” are at higher risk of rebleeding.16

Outcomes are much better when patients are managed in a high-volume center, with a specialized neurointensive care unit17 and access to an interdisciplinary team.18 Regardless of the initial grade, patients with aneurysmal subarachnoid hemorrhage should be quickly transferred to a high-volume center, defined as one treating at least 35 cases per year, and the benefit is greater in centers treating more than 60 cases per year.19 The higher the caseload in any given hospital, the better the clinical outcomes in this population.20

Treating cerebral aneurysm: Clipping or coiling

Early aneurysm repair is generally considered the standard of care and the best strategy to reduce the risk of rebleeding. Further, early treatment may be associated with a lower risk of delayed cerebral ischemia21 and better outcomes.22

Three randomized clinical trials have compared surgical clipping and endovascular repair (placement of small metal coils within the aneurysm to promote clotting).

The International Subarachnoid Aneurysm Trial23 showed a reduction of 23% in relative risk and of 7% in absolute risk in patients who underwent endovascular treatment compared with surgery. The survival benefit persisted at a mean of 9 years (range 6–14 years), but with a higher annual rate of aneurysm recurrence in the coiling group (2.9% vs 0.9%).24 Of note, this trial included only patients with aneurysms deemed suitable for both coiling and clipping, so that the exclusion rate was high. Most of the patients presented with good-grade (WFNS score 1–3), small aneurysms (< 5 mm) in the anterior circulation.

A single-center Finnish study25 found no differences in rates of recovery, disability, and death at 1 year, comparing surgery and endovascular treatment. Additionally, survival rates at a mean follow-up of 39 months were similar, with no late recurrences or aneurysmal bleeding.

Lastly, the Barrow Ruptured Aneurysm Trial26,27 found that patients assigned to endovascular treatment had better 1-year neurologic outcomes, defined as a modified Rankin score of 2 or less. Importantly, 37.7% of patients originally assigned to endovascular treatment crossed over to surgical treatment. The authors then performed intention-to-treat and as-treated analyses. Either way, patients treated by endovascular means had better neurologic outcomes at 1 year. However, no difference in the relative risk reduction in worse outcome was found on 3-year follow-up, and patients treated surgically had higher rates of aneurysm obliteration and required less aneurysm retreatment, both of which were statistically significant.

The question that remains is not whether to clip or whether to coil, but whom to clip and whom to coil.28 That question must be answered on a patient-to-patient basis and requires the expertise of an interventional neuroradiologist and a vascular neurosurgeon—one of the reasons these patients are best cared for in high-volume centers providing such expertise.

MEDICAL PREVENTION OF REBLEEDING

Blood pressure management

There are no systematic data on the optimal blood pressure before securing an aneurysm. Early studies of hemodynamic augmentation in cases of ruptured untreated aneurysm reported rebleeding when the systolic blood pressure was allowed to rise above 160 mm Hg.29,30 A recent study evaluating hypertensive intracerebral hemorrhage revealed better functional outcomes with intensive lowering of blood pressure (defined as systolic blood pressure < 140 mm Hg) but no significant reduction in the combined rate of death or severe disability.31 It is difficult to know if these results can be extrapolated to patients with aneurysmal subarachnoid hemorrhage. Current guidelines3,32 say that before the aneurysm is treated, the systolic pressure should be lower than 160 mm Hg.

There is no specific drug of choice, but a short-acting, titratable medication is preferable. Nicardipine is a very good option, and labetalol might be an appropriate alternative.33 Once the aneurysm is secured, all antihypertensive drugs should be held. Hypertension should not be treated unless the patient has clinical signs of a hypertensive crisis, such as flash pulmonary edema, myocardial infarction, or hypertensive encephalopathy.

Antifibrinolytic therapy

The role of antifibrinolytic therapy in aneurysmal subarachnoid hemorrhage is controversial and has been studied in 10 clinical trials. In a Swedish study,34 early use of tranexamic acid (1 g intravenously over 10 minutes followed by 1 g every 6 hours for a maximum of 24 hours) reduced the rebleeding rate substantially, from 10.8% to 2.4%, with an 80% reduction in the mortality rate from ultra-early rebleeding. However, a recent Cochrane review that included this study found no overall benefit.35

An ongoing multicenter randomized trial in the Netherlands will, we hope, answer this question in the near future.36 At present, some centers would consider a short course of tranexamic acid before aneurysm treatment.

DIAGNOSIS AND TREATMENT OF COMPLICATIONS

Medical complications are extremely common after aneurysmal subarachnoid hemorrhage. Between 75% and 100% of patients develop some type of systemic or further neurologic derangement, which in turn has a negative impact on the long-term outcome.37,38 In the first 72 hours, rebleeding is the most feared complication, and as mentioned previously, appropriate blood pressure management and early securing of the aneurysm minimize its risk.

NEUROLOGIC COMPLICATIONS

Hydrocephalus

Hydrocephalus is the most common early neurologic complication after aneurysmal subarachnoid hemorrhage, with an overall incidence of 50%.39 Many patients with poor-grade aneurysmal subarachnoid hemorrhage and patients whose condition deteriorates due to worsening of hydrocephalus require the insertion of an external ventricular drain (Figure 1).

Up to 30% of patients who have a poor-grade aneurysmal subarachnoid hemorrhage improve neurologically with cerebrospinal fluid drainage.40 An external ventricular drain can be safely placed, even before aneurysm treatment, and placement does not appear to increase the risk of rebleeding.39,41 After placement, rapid weaning from the drain (clamping within 24 hours of insertion) is safe, decreases length of stay in the intensive care unit and hospital, and may be more cost-effective than gradual weaning over 96 hours.42

Increased intracranial pressure

Intracranial hypertension is another potential early complication, and is frequently due to the development of hydrocephalus, cerebral edema, or rebleeding. The treatment of increased intracranial pressure does not differ from the approach used in managing severe traumatic brain injury, which includes elevating the head of the bed, sedation, analgesia, normoventilation, and cerebrospinal fluid drainage.

Hypertonic saline has been tested in several studies that were very small but nevertheless consistently showed control of intracranial pressure levels and improvement in cerebral blood flow measured by xenon CT.43–47 Two of these studies even showed better outcomes at discharge.43,44 However, the small number of patients prevents any meaningful conclusion regarding the use of hypertonic saline and functional outcomes.

Barbiturates, hypothermia, and decompressive craniectomy could be tried in refractory cases.48 Seule et al49 evaluated the role of therapeutic hypothermia with or without barbiturate coma in 100 patients with refractory intracranial hypertension. Only 13 patients received hypothermia by itself. At 1 year, 32 patients had achieved a good functional outcome (Glasgow Outcome Scale score 4 or 5). The remaining patients were severely disabled or had died. Of interest, the median duration of hypothermia was 7 days, and 93% of patients developed some medical complication such as electrolyte disorders (77%), pneumonia (52%), thrombocytopenia (47%), or septic shock syndrome (40%). Six patients died as a consequence of one of these complications.

Decompressive craniectomy can be life-saving in patients with refractory intracranial hypertension. However, most of these patients will die or remain severely disabled or comatose.50

Seizure prophylaxis is controversial

Seizures can occur at the onset of intracranial hemorrhage, perioperatively, or later (ie, after the first week). The incidence varied considerably in different reports, ranging from 4% to 26%.51 Seizures occurring perioperatively, ie, after hospital admission, are less frequent and are usually the manifestation of aneurysm rebleeding.24

Seizure prophylaxis remains controversial, especially because the use of phenytoin is associated with increased incidence of cerebral vasospasm, infarction, and worse cognitive outcomes after aneurysmal subarachnoid hemorrhage.52,53 Therefore, routine prophylactic use of phenytoin is not recommended in these patients,3 although the effect of other antiepileptic drugs is less studied and less clear. Patients may be considered for this therapy if they have multiple risk factors for seizures, such as intraparenchymal hematoma, advanced age (> 65), middle cerebral artery aneurysm, craniotomy for aneurysm clipping, and a short course (≤ 72 hours) of an antiepileptic drug other than phenytoin, especially while the aneurysm is unsecured.3

Levetiracetam may be an alternative to phenytoin, having better pharmacodynamic and kinetic profiles, minimal protein binding, and absence of hepatic metabolism, resulting in a very low risk of drug interaction and better tolerability.54,55 Because of these advantages, levetiracetam has become the drug of choice in several centers treating aneurysmal subarachnoid hemorrhage in the United States.

Addressing this question, a survey was sent to 25 high-volume aneurysmal subarachnoid hemorrhage academic centers in the United States. All 25 institutions answered the survey, and interestingly, levetiracetam was the first-line agent for 16 (94%) of the 17 responders that used prophylaxis, while only 1 used phenytoin as the agent of choice.56

A retrospective cohort study by Murphy-Human et al57 showed that a short course of levetiracetam (≤ 72 hours) was associated with higher rates of in-hospital seizures compared with an extended course of phenytoin (eg, entire hospital stay). However, the study did not address functional outcomes.57

Continuous electroencephalographic monitoring may be considered in comatose patients, in patients requiring controlled ventilation and sedation, or in patients with unexplained alteration in consciousness. In one series of patients with aneurysmal subarachnoid hemorrhage who received continuous monitoring, the incidence of nonconvulsive status epilepticus was 19%, with an associated mortality rate of 100%.58

Continuous quantitative electroencephalography is useful to monitor and to detect angiographic vasospasm and delayed cerebral ischemia. Relative alpha variability and the alpha-delta ratio decrease with ischemia, and this effect can precede angiographic vasospasm by 3 days.59,60

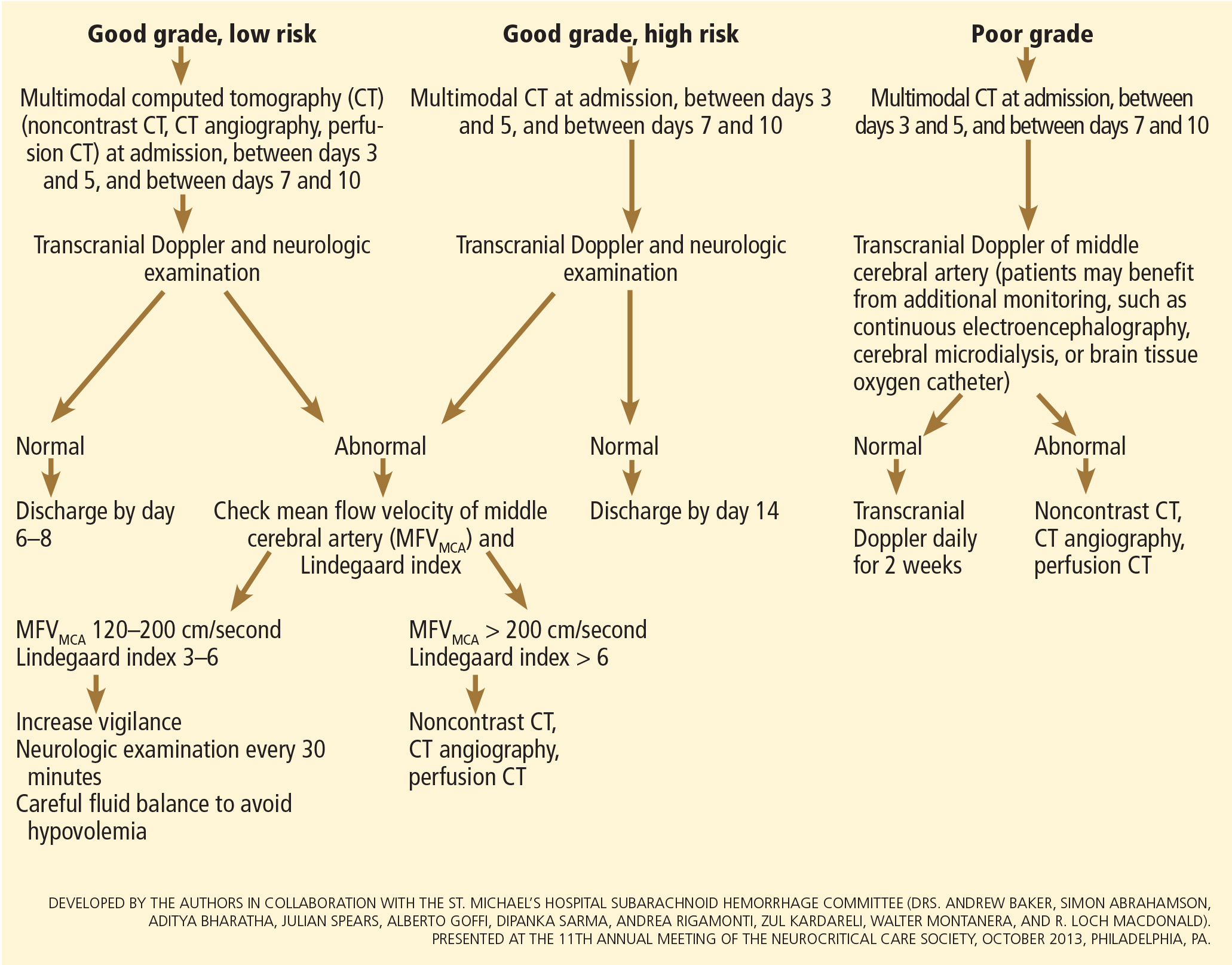

Delayed cerebral ischemia

Delayed cerebral ischemia is defined as the occurrence of focal neurologic impairment, or a decrease of at least 2 points on the Glasgow Coma Scale that lasts for at least 1 hour, is not apparent immediately after aneurysm occlusion, and not attributable to other causes (eg, hyponatremia, fever).61

Classically, neurologic deficits that occurred within 2 weeks of aneurysm rupture were ascribed to reduced cerebral blood flow caused by delayed large-vessel vasospasm causing cerebral ischemia.62 However, perfusion abnormalities have also been observed with either mild or no demonstrable vasospasm.63 Almost 70% of patients who survive the initial hemorrhage develop some degree of angiographic vasospasm. However, only 30% of those patients will experience symptoms.

In addition to vasospasm of large cerebral arteries, impaired autoregulation and early brain injury within the first 72 hours following subarachnoid hemorrhage may play important roles in the development of delayed cerebral ischemia.64 Therefore, the modern concept of delayed cerebral ischemia monitoring should focus on cerebral perfusion rather than vessel diameter measurements. This underscores the importance of comprehensive, standardized monitoring techniques that provide information not only on microvasculature, but also at the level of the microcirculation, with information on perfusion, oxygen utilization and extraction, and autoregulation.

Although transcranial Doppler has been the most commonly applied tool to monitor for angiographic vasospasm, it has a low sensitivity and negative predictive value.37 It is nevertheless a useful technique to monitor good-grade aneurysmal subarachnoid hemorrhage patients (WFNS score 1–3) combined with frequent neurologic examinations (Figure 3).

CT angiography is a good noninvasive alternative to digital subtraction angiography. However, it tends to overestimate the degree of vasoconstriction and does not provide information about perfusion and autoregulation.65 Nevertheless, CT angiography combined with a CT perfusion scan can add information about autoregulation and cerebral perfusion and has been shown to be more sensitive for the diagnosis of angiographic vasospasm than transcranial Doppler and digital subtraction angiography (Figure 4).

Patients with a poor clinical condition (WFNS score 4 or 5) or receiving continuous sedation constitute a challenge in monitoring for delayed neurologic deterioration. Neurologic examination is not sensitive enough in this setting to detect subtle changes. In these specific and challenging circumstances, multimodality neuromonitoring may be useful in the early detection of delayed cerebral ischemia and may help guide therapy.67

Several noninvasive and invasive techniques have been studied to monitor patients at risk of delayed cerebral ischemia after subarachnoid hemorrhage.66 These include continuous electroencephalography, brain tissue oxygenation monitoring (Ptio2), cerebral microdialysis, thermal diffusion flowmetry, and near-infrared spectroscopy. Of these techniques, Ptio2, cerebral microdialysis, and continuous electroencephalography (see discussion of seizure prophylaxis above) have been more extensively studied. However, most of the studies were observational and very small, limiting any recommendations for using these techniques in routine clinical practice.68

Ptio2 is measured by inserting an intraparenchymal oxygen-sensitive microelectrode, and microdialysis requires a microcatheter with a semipermeable membrane that allows small soluble substances to cross it into the dialysate. These substances, which include markers of ischemia (ie, glucose, lactate, and pyruvate), excitotoxins (ie, glutamate and aspartate), and membrane cell damage products (ie, glycerol), can be measured. Low Ptio2 values (< 15 mm Hg) and abnormal mycrodialysate findings (eg, glucose < 0.8 mmol/L, lactate-to-pyruvate ratio > 40) have both been associated with cerebral ischemic events and poor outcome.68

Preventing delayed cerebral ischemia

Oral nimodipine 60 mg every 4 hours for 21 days, started on admission, carries a class I, level of evidence A recommendation in the management of aneurysmal subarachnoid hemorrhage.3,32,69 It improves clinical outcome despite having no effect on the risk of angiographic vasospasm. The mechanism of improved outcome is unclear, but the effect may be a neuroprotective phenomenon limiting the extension of delayed cerebral ischemia.70

If hypotension occurs, the dose can be lowered to 30 mg every 2 hours. Whether to discontinue nimodipine in this situation is controversial. Of note, the clinical benefits of nimodipine have not been replicated with other calcium channel blockers (eg, nicardipine).71

Prophylactic hyperdynamic fluid therapy, known as “triple-H” (hypervolemia, hemodilution, and hypertension) was for years the mainstay of treatment in preventing delayed cerebral ischemia due to vasospasm. However, the clinical data supporting this intervention have been called into question, as analysis of two trials found that hypervolemia did not improve outcomes or reduce the incidence of delayed cerebral ischemia, and in fact increased the rate of complications.72,73 Based on these findings, current guidelines recommend maintaining euvolemia rather than prophylactic hypervolemia in patients with aneurysmal subarachnoid hemorrhage.3,32,69