Recognizing and managing hereditary angioedema

ABSTRACTHereditary angioedema is a rare but life-threatening disease characterized by recurring attacks of swelling of any part of the body, without hives. Prompt recognition is critical so that treatment can be started to minimize morbidity and the risk of death. Drugs have recently become available to prevent and treat acute attacks.

KEY POINTS

- Swelling in the airways is life-threatening and requires rapid treatment.

- Almost half of attacks involve the abdomen, and abdominal attacks account for many emergency department visits, hospitalizations, and unnecessary surgical procedures for acute abdomen.

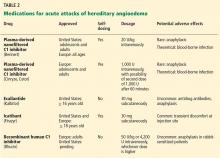

- Acute attacks can be managed with plasma-derived or recombinant human preparations of C1 inhibitor (which is the deficient factor in this condition), ecallantide (a specific plasma kallikrein inhibitor), or icatibant (a B2 bradykinin receptor antagonist).

- Short-term prophylaxis may be used before events that could provoke attacks (eg, dental work or surgery). Long-term prophylaxis may be used in patients who have frequent or severe attacks or require more stringent control of their disease. Plasma-derived C1 inhibitor is both safe and effective when used as prophylaxis. Attenuated androgens are effective but associated with many adverse effects.

Hereditary angioedema with normal C1 inhibitor levels

Hereditary angioedema with normal C1 inhibitor levels is also inherited in an autosomal dominant pattern. It is often estrogen-sensitive, making it more severe in women. Symptoms tend to develop slightly later in life than in type I or II disease.7

Angioedema with normal C1 inhibitor levels has been associated with factor XII mutations in a minority of cases, but most patients do not have a specific laboratory abnormality. Because there is no specific laboratory profile, the diagnosis is based on clinical criteria. Hereditary angioedema with normal C1 inhibitor levels should be considered in patients who have recurrent angioedema, normal C4, normal antigenic and functional C1 inhibitor levels, a lack of response to high-dose antihistamines, and either a family history of angioedema without hives or a known factor XII mutation.7 However, other forms of angioedema (allergic, drug-induced, and idiopathic) should also be considered, as C4 and C1 inhibitor levels are normal in these forms as well.

DIFFERENTIAL DIAGNOSIS: OTHER TYPES OF ANGIOEDEMA

Acquired C1 inhibitor deficiency

Symptoms of acquired C1 inhibitor deficiency resemble those of hereditary angioedema but typically do not emerge until the fourth decade of life or later, and patients have no family history of the condition. It is often associated with other diseases, most commonly B-cell lymphoproliferative disorders, which cause uncontrolled complement activation and consumption of C1 inhibitor.

In some patients, autoantibodies to C1 inhibitor develop, greatly reducing its effectiveness and resulting in enhanced consumption. The autoantibody is often associated with a monoclonal gammopathy of unknown significance. The presence of a C1 inhibitor autoantibody does not preclude the presence of an underlying disorder, and vice versa.

Laboratory studies reveal low C4, low C1-inhibitor antigenic and functional levels, and usually a low C1q level owing to consumption of complement. Autoantibodies to C1 inhibitor can be detected by laboratory testing.

Because of the association with autoimmune disease and malignant disorders (especially B-cell malignancy), a patient diagnosed with acquired C1 inhibitor deficiency should be further evaluated for underlying conditions.

Allergic angioedema

Allergic angioedema results from preformed antigen-specific immunoglobulin E (IgE) antibodies that stimulate mast cells to degranulate when patients are exposed to a particular allergen—most commonly food, insect venom, latex, or drugs. IgE-mediated histamine release causes swelling, as histamine is a potent vasodilator.

Symptoms often begin within 2 hours of exposure to the allergen and generally include concurrent urticaria and swelling that last less than 24 hours. Unlike in hereditary angioedema, the swelling responds to antihistamines and corticosteroids. When very severe, these symptoms may also be accompanied by bronchoconstriction and gastrointestinal symptoms, especially if the allergen is ingested.

Histamine-mediated angioedema may also be associated with exercise as part of a syndrome called exercise-induced anaphylaxis or angioedema.

Drug-induced angioedema

Drug-induced angioedema is typically associated with angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitors or nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs).

Angioedema associated with ACE inhibitors is estimated to affect 0.1% to 6% of patients taking these medications, with African Americans being at significantly higher risk. Although 25% of affected patients develop symptoms of angioedema within the first month of taking the drugs, some tolerate them for as long as 10 years before the first episode.9 The swelling is not allergic or histamine-related. ACE normally degrades bradykinin; therefore, inhibiting ACE leads to accumulation of bradykinin. Because all ACE inhibitors have this effect, this class of drug should be discontinued in any patient who develops isolated angioedema.

NSAID-induced angioedema is often accompanied by other symptoms, including urticaria, rhinitis, cough, hoarseness, or breathlessness.10 The mechanism of NSAID-induced angioedema involves cyclooxygenase (COX) 1 (and to a lesser extent COX-2) inhibition. All NSAIDs (and aspirin) should be avoided in patients with recurrent angioedema. Specific COX-2 inhibitors, while theoretically capable of causing angioedema by the same mechanism, are generally well tolerated in patients who have had COX-1 inhibitor reactions.

Idiopathic angioedema

If no clear cause of recurrent angioedema (at least three episodes in a year) can be found, it is labeled idiopathic.11 Some patients with idiopathic angioedema fail to benefit from high doses of antihistamines, suggesting that the cause is bradykinin-mediated.

CLINICAL MANIFESTATIONS OF HEREDITARY ANGIOEDEMA

Attacks may start at one site and progress to involve additional sites.

Prodromal symptoms may begin up to several days before an attack and include tingling, warmth, burning, or itching at the affected site; increased fatigue or malaise; nausea, abdominal distention, or gassiness; or increased hunger, particularly before an abdominal attack.5 The most characteristic prodromal symptom is erythema marginatum—a raised, serpiginous, nonpruritic rash on the trunk, arms, and legs but often sparing the face.

Abdominal attacks are easily confused with acute abdomen

Almost half of attacks involve the abdomen, and almost all patients with type I or II disease experience at least one such attack.12 Symptoms can include severe abdominal pain, nausea, vomiting, and diarrhea. Abdominal attacks account for many emergency department visits, hospitalizations, and surgical procedures for acute abdomen; about one-third of patients with undiagnosed hereditary angioedema undergo an unnecessary surgery during an abdominal attack. Angioedema of the gastrointestinal tract can result in enough plasma extravasation and vasodilation to cause hypovolemic shock.

Eradicating Helicobacter pylori infection may alleviate abdominal attacks.13

Attacks of the extremities can be painful and disabling

Attacks of the extremities affect 96% of patients12 and can be very disfiguring and disabling. Driving or using the phone is often difficult when the hands are affected. When feet are involved, walking and standing become painful. While these symptoms rarely result in a lengthy hospitalization, they interfere with work and school and require immediate medical attention because they can progress to other parts of the body.

Laryngeal attacks are life-threatening

About half of patients with hereditary angioedema have an attack of laryngeal edema at some point in their lives.12 If not effectively managed, laryngeal angioedema can progress to asphyxiation. A survey of family history in 58 patients with hereditary angioedema suggested a 40% incidence of asphyxiation in untreated laryngeal attacks, and 25% to 30% of patients are estimated to have died of laryngeal edema before effective treatment became available.14

Symptoms of a laryngeal attack include change in voice, hoarseness, trouble swallowing, shortness of breath, and wheezing. Physicians must recognize these symptoms quickly and give effective treatment early in the attack to prevent morbidity and death.

Establishing an airway can be life-saving in the absence of effective therapy, but extensive swelling of the upper airway can make intubation extremely difficult.

Genitourinary attacks also occur

Attacks involving the scrotum and labia have been reported in up to two-thirds of patients with hereditary angioedema at some point in their lives. Attacks involving the bladder and kidneys have also been reported but are less common, affecting about 5% of patients.12 Genitourinary attacks may be triggered by local trauma, such as horseback riding or sexual intercourse, although no trigger may be evident.

MANAGING ACUTE ATTACKS

The goals of treatment are to alleviate acute exacerbations with on-demand treatment and to reduce the number of attacks with prophylaxis. Therapy should be individualized to each patient’s needs. Treatments have advanced greatly in the last several years, and new medications for treating acute attacks and preventing attacks have shown great promise (Figure 3, Table 2).

Patients tend to have recurrent symptoms interspersed with periods of health, suggesting that attacks ought to have identifiable triggers, although in most, no trigger is evident. The most commonly identified are local trauma (including medical and dental procedures), emotional stress, and acute infection. Disease severity may be worsened by menstruation, estrogen-containing oral contraceptives, hormone replacement therapy, ACE inhibitors, and NSAIDs.

It is critical that attacks be treated with an effective medication as soon as possible. Consensus guidelines state that all patients with hereditary angioedema due to C1 inhibitor deficiency, even if they are still asymptomatic, should have access to at least one of the drugs approved for on-demand treatment.15 The guidelines further state that whenever possible, “patients should have the on-demand medicine to treat acute attacks at home and should be trained to self-administer these medicines.”15