Recognizing and managing hereditary angioedema

ABSTRACTHereditary angioedema is a rare but life-threatening disease characterized by recurring attacks of swelling of any part of the body, without hives. Prompt recognition is critical so that treatment can be started to minimize morbidity and the risk of death. Drugs have recently become available to prevent and treat acute attacks.

KEY POINTS

- Swelling in the airways is life-threatening and requires rapid treatment.

- Almost half of attacks involve the abdomen, and abdominal attacks account for many emergency department visits, hospitalizations, and unnecessary surgical procedures for acute abdomen.

- Acute attacks can be managed with plasma-derived or recombinant human preparations of C1 inhibitor (which is the deficient factor in this condition), ecallantide (a specific plasma kallikrein inhibitor), or icatibant (a B2 bradykinin receptor antagonist).

- Short-term prophylaxis may be used before events that could provoke attacks (eg, dental work or surgery). Long-term prophylaxis may be used in patients who have frequent or severe attacks or require more stringent control of their disease. Plasma-derived C1 inhibitor is both safe and effective when used as prophylaxis. Attenuated androgens are effective but associated with many adverse effects.

Hereditary angioedema due to deficiency of C1 inhibitor is a rare autosomal dominant disease that can be life-threatening. It affects about 1 in 50,000 people,1 or about 6,000 people in the United States. There are no known differences in prevalence by ethnicity or sex. A form of hereditary angioedema with normal C1 inhibitor levels has also recently been identified.

Despite a growing awareness of hereditary angioedema in the medical community, repeated surveys have found an average gap of 10 years between the first appearance of symptoms and the correct diagnosis. In view of the risk of morbidity and death, recognizing this disease sooner is critical.

This article will discuss how to recognize hereditary angioedema and how to differentiate it from other forms of recurring angioedema. We will also review its acute and long-term management, with special attention to new therapies and clinical challenges.

EPISODES OF SWELLING WITHOUT HIVES

Hereditary angioedema involves recurrent episodes of nonpruritic, nonpitting, subcutaneous and submucosal edema that can affect the face, tongue, larynx, trunk, extremities, bowels, or genitals. Attacks typically follow a predictable course: swelling that increases slowly and continuously for 24 hours and then gradually subsides over the next 48 to 72 hours. Attacks that involve the oropharynx, larynx, or abdomen carry the highest risk of morbidity and death.1

The frequency and severity of attacks are highly variable and unpredictable. A few patients have no attacks, a few have two attacks per week, and most fall in between.

Hives suggests an allergic or idiopathic rather than hereditary cause and will not be discussed here in detail. A history of angioedema that was rapidly aborted by antihistamines, corticosteroids, or epinephrine also suggests an allergic rather than hereditary cause.

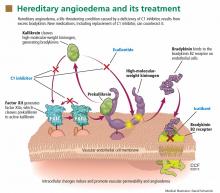

UNCHECKED BRADYKININ PRODUCTION

Substantial evidence indicates that hereditary angioedema results from extravasation of plasma into deeper cutaneous or mucosal compartments as a result of overproduction of the vasoactive mediator bradykinin (Figure 1).

Activated factor XII cleaves plasma prekallikrein to generate active plasma kallikrein (which, in turn, activates more factor XII).2 Once generated, plasma kallikrein cleaves high-molecular-weight kininogen, releasing bradykinin. Bradykinin binds to the B2 bradykinin receptor on endothelial cells, increasing the permeability of the endothelium.

Normally, C1 inhibitor helps control bradykinin production by inhibiting plasma kallikrein and activated factor XII. Without enough C1 inhibitor, the contact system is uninhibited and results in bradykinin being inappropriately generated.

Because the attacks of hereditary angioedema involve excessive bradykinin, they do not respond to the usual treatments for anaphylaxis and allergic angioedema (which involve mast cell degranulation), such as antihistamines, corticosteroids, and epinephrine.

TWO TYPES OF HEREDITARY ANGIOEDEMA

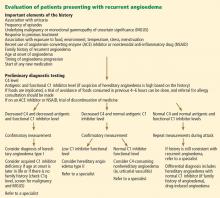

Figure 2 shows the evaluation of patients with suspected hereditary angioedema.

Hereditary angioedema due to C1 inhibitor deficiency

The classic forms of hereditary angioedema (types I and II) involve loss-of-function mutations in SERPING1—the gene that encodes for C1 inhibitor—resulting in low levels of functional C1 inhibitor.3 The mutation is inherited in an autosomal dominant pattern; however, in about 25% of cases, it appears to arise spontaneously,4 so a family history is not required for diagnosis.

Although C1 inhibitor deficiency is present from birth, the clinical disease most commonly presents for the first time when the patient is of school age. Half of patients have their first episode in the first decade of life, and another one-third first develop symptoms over the next 10 years.5

Clinically, types I and II are indistinguishable. Type I, accounting for 85% of cases,1 results from low production of C1 inhibitor. Laboratory studies reveal low antigenic and functional levels of C1 inhibitor.

In type II, the mutant C1 inhibitor protein is present but dysfunctional and unable to inhibit target proteases. On laboratory testing, the functional level of C1 inhibitor is low but its antigenic level is normal (Table 1). Function can be tested by either chromogenic assay or enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay; the former is preferred because it is more sensitive.6

Because C1 inhibitor deficiency results in chronic activation of the complement system, patients with type I or II disease usually have low C4 levels regardless of disease activity, making measuring C4 the most economical screening test. When suspicion for hereditary angioedema is high, based on the presentation and family and clinical history, measuring antigenic and functional C1 inhibitor levels and C4 simultaneously is more efficient.