Human papillomavirus vaccine: Safe, effective, underused

ABSTRACTVaccination against human papillomavirus (HPV) is safe and effective. It is recommended for females age 9 to 26 and for males age 11 to 26, yet vaccination rates are low. We review the host immune response, the data behind the recommendations for HPV vaccination, and the challenges of implementing the vaccination program.

KEY POINTS

- Two HPV vaccines are available: a quadrivalent vaccine against HVP types 6, 11, 16, and 18, and a bivalent vaccine against types 16 and 18.

- HPV causes cervical cancer, genital warts, oropharyngeal cancer, anal cancer, and recurrent respiratory papillomatosis, creating a considerable economic and health burden.

- The host immune response to natural HPV infection is slow and weak. In contrast, HPV vaccine induces a strong and long-lasting immune response.

- The HPV vaccines have greater than 90% efficacy in preventing cervical dysplasia and genital warts that are caused by the HPV types the vaccine contains. They are as safe as other common prophylactic vaccines.

- HPV vaccination has been challenged by public controversy over the vaccine’s safety, teenage sexuality, mandatory legislation, and the cost of the vaccine.

VACCINATION INDUCES A STRONGER IMMUNE RESPONSE THAN INFECTION

HPV infections trigger both a humoral and a cellular response in the host immune system.

The humoral immune response to HPV infection involves producing neutralizing antibody against the specific HPV type, specifically the specific L1 major capsid protein. This process is typically somewhat slow and weak, and only about 60% of women with a new HPV infection develop antibodies to it.36,37

HPV has several ways to evade the host immune system. It does not infect or replicate within the antigen-presenting cells in the epithelium. In addition, HPV-infected keratinocytes are less susceptible to cytotoxic lymphocytic-mediated lysis. Moreover, HPV infection cause very little tissue destruction. And finally, natural cervical HPV infection does not result in viremia. As a result, antigen-presenting cells have no chance to engulf the virions and present virion-derived antigen to the host immune system. The immune system outside the epithelium has limited opportunity to detect the virus because HPV infection does not have a blood-borne phase.38,39

The cell-mediated immune response to early HPV oncoproteins may help eliminate established HPV infection.40 In contrast to antibodies, the T-cell response to HPV has not been shown to be specific to HPV type.41 Clinically, cervical HPV infection is common, but most lesions go into remission or resolve as a result of the cell-mediated immune response.40,41

In contrast to the weak, somewhat ineffective immune response to natural HPV infection, the antibody response to HPV vaccines is rather robust. In randomized controlled trials, almost all vaccinated people have seroconverted. The peak antibody concentrations are 50 to 10,000 times greater than in natural infection. Furthermore, the neutralizing antibodies induced by HPV vaccines persist for as long as 7 to 9 years after immunization.42 However, the protection provided by HPV vaccines against HPV-related cervical intraepithelial neoplasia does not necessarily correlate with the antibody concentration.43–47

Why does the vaccine work so well?

Why are vaccine-induced antibody responses so much stronger than those induced by natural HPV infection?

The first reason is that the vaccine, delivered intramuscularly, rapidly enters into blood vessels and the lymphatic system. In contrast, in natural intraepithelial infection, the virus is shed from mucosal surfaces and does not result in viremia.48

In addition, the strong immunogenic nature of the virus-like particles induces a robust host antibody response even in the absence of adjuvant because of concentrated neutralizing epitopes and excellent induction of the T-helper cell response.35,49,50

The neutralizing antibody to L1 prevents HPV infection by blocking HPV from binding to the basement membrane as well as to the epithelial cell receptor during epithelial microabrasion and viral entry. The subsequent micro-wound healing leads to serous exudation and rapid access of serum immunoglobulin G (IgG) to HPV virus particles and encounters with circulatory B memory cells.

Furthermore, emerging evidence suggests that even very low antibody concentrations are sufficient to prevent viral entry into cervical epithelial cells.46–48,51–53

THE HPV VACCINES ARE HIGHLY EFFECTIVE AND SAFE

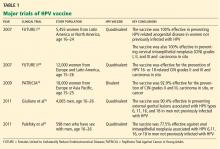

The efficacy and safety of the quadrivalent and the bivalent HPV vaccines have been evaluated in large randomized clinical trials.23,28,29,54,55 Table 1 summarizes the key findings.

The Females United to Unilaterally Reduce Endo/ectocervical Disease (FUTURE I)54 and FUTURE II28 trials showed conclusively that the quadrivalent HPV vaccine is 98% to 100% efficacious in preventing HPV 16- and 18-related cervical intraepithelial neoplasia, carcinoma in situ, and invasive cervical cancer in women who had not been infected with HPV before. Similarly, the Papilloma Trial against Cancer in Young Adults (PATRICIA) concluded that the bivalent HPV vaccine is 93% efficacious.29

Giuliano et al55 and Palefsky et al23 conducted randomized clinical trials of the quadrivalent HPV vaccine for preventing genital disease and anal intraepithelial neoplasia in boys and men; the efficacy rates were 90.4%55 and 77.5%.23

A recent Finnish trial in boys age 10 to 18 found 100% seroconversion rates for HPV 16 and HPV 18 antibodies after they received bivalent HPV vaccine.56 Similar efficacy has been demonstrated for the quadrivalent HPV vaccine in boys.57

Adverse events after vaccination

After the FDA approved the quadrivalent HPV vaccine for girls in 2006, the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) conducted a thorough survey of adverse events after immunization from June 1, 2006 through December 31, 2008.58 There were about 54 reports of adverse events per 100,000 distributed vaccine doses, similar to rates for other vaccines. However, the incidence rates of syncope and venous thrombosis were disproportionately higher, according to data from the US Vaccine Adverse Event Reporting System. The rate of syncope was 8.2 per 100,000 vaccine doses, and the rate of venous thrombotic events was 0.2 per 100,000 doses.58

There were 32 reports of deaths after HPV vaccination, but these were without clear causation. Hence, this information must be interpreted with caution and should not be used to infer causal associations between HPV vaccines and adverse outcomes. The causes of death included diabetic ketoacidosis, pulmonary embolism, prescription drug abuse, amyotrophic lateral sclerosis, meningoencephalitis, influenza B viral sepsis, arrhythmia, myocarditis, and idiopathic seizure disorder.58

Furthermore, it is important to note that vasovagal syncope and venous thromboembolic events are more common in young females in general.59 For example, the background rates of venous thromboembolism in females age 14 to 29 using oral contraceptives is 21 to 31 per 100,000 woman-years.60

Overall, the quadrivalent HPV vaccine is well tolerated and clinically safe. Postlicensure evaluation found that the quadrivalent and bivalent HPV vaccines had similar safety profiles.61

Vaccination is contraindicated in people with known hypersensitivity or prior severe allergic reactions to vaccine or yeast or who have bleeding disorders.

HPV VACCINATION DOES MORE THAN PREVENT CERVICAL CANCER IN FEMALES

The quadrivalent HPV vaccine was licensed by the FDA in 2006 for use in females age 9 to 26 to prevent cervical cancer, cervical cancer precursors, vaginal and vulval cancer precursors, and anogenital warts caused by HPV types 6, 11, 16, and 18. The CDC’s Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP) issued its recommendation for initiating HPV vaccination for females age 11 to 12 in March 2007. The ACIP stated that the vaccine could be given to girls as early as age 9 and recommended catch-up vaccinations for those age 13 to 26.62,63

The quadrivalent HPV vaccine was licensed by the FDA in 2009 for use in boys and men for the prevention of genital warts. In December 2010, the quadrivalent HPV vaccine received extended licensure from the FDA for use in males and females for the prevention of anal cancer. In October 2011, the ACIP voted to recommend routine use of the quadrivalent HPV vaccine for boys age 11 to 12; catch-up vaccination should occur for those age 13 to 22, with an option to vaccinate men age 23 to 26.

These recommendations replace the “permissive use” recommendations from the ACIP in October 2009 that said the quadrivalent HPV vaccine may be given to males age 9 to 26.64 This shift from a permissive to an active recommendation connotes a positive change reflecting recognition of rising oropharyngeal cancer rates attributable to oncogenic, preventable HPV, rising HPV-related anal cancer incidence, and the burden of the disease in female partners of infected men, with associated rising health care costs.

The bivalent HPV vaccine received FDA licensure in October 2009 for use in females age 10 to 25 to prevent cervical cancer and precursor lesions. The ACIP included the bivalent HPV vaccine in its updated recommendations in May 2010 for use in girls age 11 to 12. Numerous national and international organizations have endorsed HPV vaccination.65–71

Table 2 outlines the recommendations from these organizations.