A 37-year-old man with a chronic cough

Pneumocystis jirovecii

P jirovecii was previously known as P carinii, and P jirovecii pneumonia is an AIDS-defining illness. Most cases occur when the CD4 count falls below 200 cells/μL.1 Symptoms, including a nonproductive cough, develop insidiously over days to weeks.

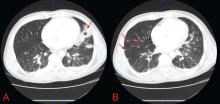

Physical examination may reveal inspiratory crackles; however, half of the time the physical examination is nondiagnostic. Oral candidiasis is a common coinfection. The lactate dehydrogenase level may be elevated.1,8 Radiographs show bilateral interstitial infiltrates, and in 10% to 20% of patients lung cysts develop—hence the name of the organism.1 Pneumothorax in a patient with HIV should prompt a workup for P jirovecii pneumonia.9,10

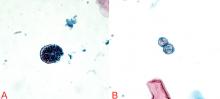

No consensus exists for the diagnosis. However, if sputum examination is unrevealing but suspicion is high, then bronchoalveolar lavage can help.11–13

Trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole for 21 days is the first-line treatment, with glucocorticoids added if the Pao2 is less than 70 mm Hg or if the alveolar-arterial oxygen gradient is greater than 35 mm Hg.1

Coccidioides species

Coccidioides infection is typically due to either C immitis or C posadasii.14 People living in or travelling to areas where it is endemic, such as the southwestern United States, Mexico, and Central and South America, are at higher risk.14

Typical signs and symptoms of this fungal infection include an influenza-like illness with fever, cough, adenopathy, and wasting, and when combined with erythema nodosum, erythema multiforme, arthralgia, or ocular involvement, this constellation is colloquially termed “valley fever.”15 Most HIV-infected patients who have CD4 counts higher than 250 cells/μL present with focal pneumonia, while lower counts predispose to disseminated disease.1,2,16

Findings on examination are nonspecific and depend on the various pulmonary manifestations, which include acute, chronic progressive, or diffuse pneumonia, nodules, or cavities.14 Eosinophilia may accompany the infection.15

The diagnosis can be made by finding the organisms on direct microscopic examination of involved tissues or secretions or on culture of clinical specimens.1,2,14 Serologic tests, antigen detection tests, or culture can be helpful if positive, but negative results do not rule out the diagnosis.1,2,14

A caveat about testing: if the pretest probability of infection is low, positive tests for immunoglobulin M (IgM) do not necessarily equal infection, and the IgM test should be followed up with confirmatory testing. Along the same lines, a high pretest probability should not be ignored if initial tests are negative, and patients in this situation should also undergo further evaluation.17

Therapy with an azole drug such as fluconazole (Diflucan) or one of the amphotericin B preparations should be started, depending on the severity of the disease.1,2,14,18

Candida albicans

C albicans is a rare cause of lung infection.19,20 It is, however, a common inhabitant of the upper airway tract, and pulmonary infection is usually the result of aspiration or hematogenous spread from either the gastrointestinal tract or an infected central venous catheter.20

The presentation is relatively nonspecific. Fever despite broad-spectrum antibacterial therapy is a major clue. Radiographic abnormalities usually are due to other causes, such as superimposed infections or pulmonary hemorrhage.21 Sputum culture is unreliable because of colonization. The definitive diagnosis is based on lung biopsy demonstrating organisms within the tissue.19,20,22

Therapy with a systemic antifungal agent is recommended.

Streptococcus pneumoniae

S pneumoniae is one of the most common bacterial causes of community-acquired pneumonia in people with or without HIV.23–25 Moreover, two or more episodes of bacterial pneumonia in 12 months can be an AIDS-defining condition in patients with a positive serologic test for HIV.16 Therefore, in patients with fever, cough, and pulmonary infiltrates on chest radiography, S pneumoniae must always be considered.

Urinary antigen testing has a relatively high positive predictive value (> 89%) and specificity (96%) for diagnosing S pneumoniae pneumonia.26 Blood and sputum cultures should be done not only to confirm the diagnosis, but also because the rates of bacteremia and drug resistance are higher with S pneumoniae infection in the HIV-infected.1

A combination of a beta-lactam and a macrolide or respiratory fluoroquinolone is the treatment of choice.1

Cytomegalovirus

Although influenza is the most common cause of viral pneumonia in HIV-infected people, cytomegalovirus is an opportunistic cause.2 This is usually a reactivation of latent infection rather than new infection.27 Typically, infections occur at CD4 counts lower than 50 cells/μL, with cough, dyspnea, and fever that last for 2 to 4 weeks.2

Crackles may be heard on lung examination. The lactate dehydrogenase level can be elevated, as in P jirovecii pneumonia.2 Radiography can show a wide range of nonspecific findings, from reticular and ground-glass opacities to alveolar or interstitial infiltrates to nodules.

The diagnosis of cytomegalovirus pneumonia is not always clear. Since HIV-infected patients typically shed the virus in their airways, bronchoalveolar lavage is not adequate because a positive finding does not necessarily mean the patient has active viral pneumonitis.27 For this reason, infection should be confirmed by biopsy demonstrating characteristic cytomegalovirus inclusions in lung tissue.2

Importantly, once cytomegalovirus pneumonia is confirmed, the patient should be screened for cytomegalovirus retinitis even if he or she has no visual symptoms, as cytomegalovirus pneumonitis is typically a part of a disseminated infection.1

Treatment with intravenous ganciclovir (Cytovene) is required.1

CASE CONTINUED: POSITIVE TESTS FOR COCCIDIOIDES

Our patient began empiric treatment for community-acquired pneumonia with intravenous ceftriaxone (Rocephin) and azithromycin (Zithromax).

On the basis of these findings, the patient was immediately placed in negative pressure respiratory isolation and underwent induced sputum examinations for tuberculosis. Further tests for S pneumoniae, S aureus, Mycoplasma, Legionella, influenza, Pneumocystis, Cryptococcus, Histoplasma, and Coccidioides species were performed.

QuantiFERON testing was negative, and blood cultures were sterile. The first induced sputum examination was negative for acid-fast bacilli. PCR testing for mycobacterial DNA in the sputum was also negative.

Both silver and direct fluorescent antibody staining of the sputum were negative for Pneumocystis. On the basis of these findings and the patient’s lack of clinical improvement with trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole, Pneumocystis infection was excluded.