Sessile serrated polyps: Cancer risk and appropriate surveillance

ABSTRACTSessile serrated polyps are a recently recognized type of neoplastic polyp that develops along a molecular pathway different from that of conventional adenomas. While the clinical significance of the serrated pathway to colorectal cancer is clear, further study is needed to understand a patient’s lifetime colorectal cancer risk posed by serrated neoplasms and the optimal postpolypectomy surveillance interval.

KEY POINTS

- From 20% to 30% of colorectal cancers arise through the serrated polyp pathway (the serrated neoplasia pathway.)

- Histologically, serrated polyps have a serrated or sawtooth appearance from the folding in of the crypt epithelium. Types of serrated polyps include hyperplastic polyps, traditional serrated adenomas, and sessile serrated polyps (also known as sessile serrated adenomas).

- Guidelines for surveillance after polypectomy of serrated lesions recommend that patients with a large (≥ 10-mm) or a sessile serrated polyp with cytologic dysplasia or a traditional serrated adenoma be followed more closely than patients with a sessile serrated polyp smaller than 10 mm. Patients with small rectosigmoid hyperplastic polyps should be followed the same as people at average risk.

CHALLENGES TO EFFECTIVE COLONOSCOPY

Colonoscopic polypectomy of adenomatous polyps reduces the incidence of colorectal cancer and the rate of death from it.15,16 However, recent data show that colonoscopy may not be as effective as once thought. As many as 9% of patients with colorectal cancer have had a “normal” colonoscopic examination in the preceding 3 years.17,18 In addition, the reduction in incidence and mortality rates was less for cancers in the proximal colon than for cancers in the distal colon.19,20

Possible explanations for this discrepancy include the skill of the endoscopist, technical limitations of the examination, incomplete removal of polyps, and inadequate bowel preparation. Several studies have shown that interval colorectal cancers are more likely to be found in the proximal colon and to have the same molecular characteristics as sessile serrated polyps and the serrated colorectal cancer pathway (CIMP-high and MSI-H).21,22 Therefore, it is now thought that sessile serrated polyps may account for a substantial portion of “postcolonoscopy cancers” (ie, interval cancers) that arise in the proximal colon.

Two large studies of screening colonoscopy confirmed that the ability to detect sessile serrated polyps depends greatly on the skill of the endoscopist. Hetzel et al9 studied the differences in the rates of polyp detection among endoscopists performing more than 7,000 colonoscopies. Detection rates varied significantly for adenomas, hyperplastic polyps, and sessile serrated polyps, with the greatest variability noted in the detection of sessile serrated polyps. Significant variability was also noted in the ability of the pathologist to diagnose sessile serrated polyps.9

In the other study, a strong correlation was found between physicians who are “high detectors” of adenomas and their detection rates for proximal serrated polyps.23 There is widespread acceptance that screening colonoscopy in average-risk patients age 50 and older should detect adenomas in more than 25% of men and more than 15% of women. There is no current minimum recommended detection rate for sessile serrated polyps, but some have suggested 1.5%.8

POLYPS AS PREDICTORS OF CANCER RISK

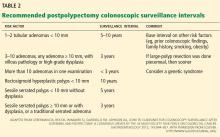

Certain polyp characteristics predict the risk of metachronous, advanced neoplasia. Advanced neoplasms are defined as invasive carcinomas, adenomas 10 mm or larger, or adenomas with any villous histology or high-grade dysplasia. Patients with one or two small tubular adenomas have a much lower risk of metachronous advanced neoplasia than do patients with more than two adenomas or advanced neoplasms.24 Current recommended surveillance intervals vary on that basis (Table 2).25

People who harbor serrated neoplasms are at high risk of synchronous serrated polyps and advanced adenomatous neoplasia. Pai et al26 found that patients with one sessile serrated polyp were four times more likely to have additional serrated polyps at the same time than an unselected population. The authors suggested that this indicates a strong colonic mucosal-field defect in patients with sessile serrated polyps, thereby predisposing them to the development of synchronous serrated polyps.

Li et al27 found that large serrated polyps (ie, > 10 mm) are associated with a risk of synchronous advanced neoplasia that is three times higher than in patients without adenomas. Schreiner et al28 determined that patients with either a proximal or a large serrated polyp were at higher risk of synchronous advanced neoplasia compared with patients who did not have those lesions. Vu et al29 found that patients who have both sessile serrated polyps and conventional adenomas have significantly larger and more numerous lesions of both types.29 In addition, these lesions are more likely to be pathologically advanced when compared with people with only one or the other type.

In the only study of the risk of advanced neoplasia on follow-up colonoscopy,28 patients with advanced neoplasia and proximal serrated polyps at baseline examination were twice as likely to have advanced neoplasia during subsequent surveillance than those with only advanced neoplasia at baseline examination.28

Therefore, it seems clear that the presence of large or proximal serrated polyps or serrated neoplasms predicts the presence of synchronous and likely metachronous advanced neoplasms.

Guidelines for postpolypectomy surveillance for individuals with serrated lesions of the colon have recently been published.25 Patients with large serrated lesions (≥ 10 mm) or an advanced serrated lesion (a sessile serrated polyp with or without cytologic dysplasia or a traditional serrated adenoma) should be followed closely. Patients with small (< 10-mm) rectosigmoid hyperplastic polyps should be followed as average-risk patients. If a patient with a sessile serrated polyp also has adenomas, the surveillance interval should be the shortest interval recommended for either lesion.29

SURVEILLANCE FOR OUR PATIENT

In our patient, given the number, size, and histologic features of the polyps found, surveillance colonoscopy should be considered in 5 years. Although the clinical significance of the serrated pathway to colorectal cancer cannot be argued, further study is required to understand the lifetime risk to patients with serrated neoplasms and the optimal surveillance interval.