Cervical cancer screening: Less testing, smarter testing

ABSTRACTIn its 2009 recommendations for cervical cancer screening, the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) calls for less-frequent but smarter screening that integrates testing for human papillomavirus (HPV) infection with the Papanicolaou (Pap) test. We review the recommendations from this and other organizations and how and why they are evolving.

KEY POINTS

- Persistent infection with one of the 18 high-risk types of HPV is associated with the development of nearly all cases of cervical cancer.

- The 2009 ACOG guidelines recommend starting to screen with the Pap test at an older age (21 years) than in the past, and they recommend a longer screening interval for women in their 20s, ie, every 2 years instead of yearly.

- Women age 30 and older should undergo both Pap and HPV testing. If both tests are negative, screening should be done again no sooner than 3 years. Alternatively, women age 30 or older who have had three consecutive negative Pap tests can be screened by Pap testing every 3 years.

- Although vaccination can prevent most primary infections with high-risk HPV, it does not eliminate the need for continuing cervical cancer screening, as it does not protect against all high-risk HPV subtypes.

- Screening can stop at age 65 to 70 in women who have had three negative Pap tests in a row and no abnormal tests within the past 10 years.

When to stop screening

The 2009 ACOG guidelines for the first time call for stopping cervical cancer screening in women 65 to 70 years of age who have had three negative Pap tests in a row and no abnormal tests in the previous 10 years.1 The American Cancer Society recommends stopping screening at age 70,65 while the US Preventive Services Task Force recommends stopping at age 65.55

Rationale. Cervical cancer develops slowly, and risk factors tend to decline with age, Also, postmenopausal mucosal atrophy may predispose to false-positive Pap results, which can lead to additional procedures and unnecessary patient anxiety.66

However, it is probably reasonable to continue screening in women age 70 and older who are sexually active with multiple partners and who have a history of abnormal Pap test results.1

Women who have had a hysterectomy

According to the latest American Cancer Society, ACOG, and US Preventive Services Task Force guidelines, cervical cancer screening should be discontinued after total hysterectomy for benign indications in women who have no history of high-grade cervical intraepithelial neoplasia, ie, CIN2 or worse.1

Rationale. If the patient has no cervix, continued vaginal cytology screening is not indicated, since the incidence of primary vaginal cancer is one to two cases per 100,000 women per year, much lower than that of cervical cancer.65

However, before discontinuing screening, clinicians should verify that any Pap tests the patient had before the hysterectomy were all read as normal, that the hysterectomy specimen was normal, and that the cervix was completely removed during hysterectomy.

Be ready to explain the recommendations

It is very important for providers to understand the evidence supporting the latest guidelines, as many patients may not realize the significant technological improvements and improved understanding of the role of HPV in cervical cancer genesis that have resulted in the deferred onset of screening and the longer intervals between screenings. This knowledge gap for patients can result in anxiety when told they no longer need an annual Pap test or can start later, if the issue is not properly and thoroughly explained by a confident provider.

A FUTURE STRATEGY: HPV AS THE SOLE PRIMARY SCREENING TEST?

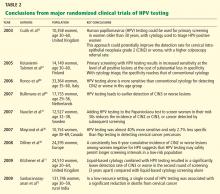

Since HPV testing is much more sensitive than Pap testing for detecting cervical lesions of grade CIN2 or higher, why not use HPV testing as the primary test and then do Pap testing (which is more specific) only if the HPV test is positive?

Mayrand et al46 conducted the first large randomized trial in which HPV testing was compared directly as a stand-alone test with the Pap test in a North American population with access to quality care. Results were published in 2007. In Canada, a total of 10,154 women ages 30 to 69 years in Montreal and St. John’s were randomly assigned to undergo either conventional Pap testing or HPV testing. The sensitivity of HPV testing for CIN2 or CIN3 was 94.6%, whereas the sensitivity of Pap testing was only 55.4%. The specificity was 94.1% for HPV testing and 96.8% for Pap testing. In addition, HPV screening followed by Pap triage resulted in fewer referrals for colposcopy than did either test alone (1.1% vs 2.9% with Pap testing alone or 6.1% with HPV testing alone). In other words, HPV testing was almost 40% more sensitive and only 2.7% less specific than Pap testing in detecting cervical cancer precursors.

However, more controlled trials are needed to validate such a strategy. Furthermore, it remains unclear if a change from Pap testing to a primary HPV testing screening strategy will further reduce the mortality rate of cervical cancer, since the burden of cervical cancer worldwide lies in less-screened populations in low-resource settings.

Dillner et al,48 in a 2008 European study, further demonstrated that HPV testing offers better long-term (6-year) predictive value for CIN3 or worse lesions than cytology does. These findings suggest that HPV testing, with its higher sensitivity and negative predictive value and its molecular focus on cervical carcinogenesis, may safely permit longer screening intervals in a low-risk population.

Sankaranarayanan et al72 performed a randomized trial in rural India in which 131,746 women age 30 to 59 years were randomly assigned to four groups: screening by HPV testing, screening by Pap testing, screening by visual inspection with acetic acid, and counseling only (the control group). At 8 years of follow-up, the numbers of cases of cervical cancer and of cervical cancer deaths were as follows:

- With HPV testing: 127 cases, 34 deaths

- With Pap testing: 152 cases, 54 deaths

- With visual inspection: 157 cases, 56 deaths

- With counseling only: 118 cases, 64 deaths.

The authors concluded that in a low-resource setting, a single round of HPV testing was associated with a significant reduction in the number of deaths from cervical cancer. Not only did the HPV testing group have a lower incidence of cancer-related deaths, there were no cancer deaths among the women in this group who tested negative for HPV. This is the first randomized trial to suggest that using HPV testing as the sole primary cervical cancer screening test may have a benefit in terms of the mortality rate.

At present, to the best of our knowledge, there are no US data validating the role of HPV testing as a stand-alone screening test for cervical cancer.