Biofeedback in headache: An overview of approaches and evidence

ABSTRACT

Biofeedback-related approaches to headache therapy fall into two broad categories: general biofeedback techniques (often augmented by relaxation-based strategies) and methods linked more directly to the pathophysiology underlying headache. The use of general biofeedback-assisted relaxation techniques for headache has been evaluated extensively by expert panels and meta-analyses. Taken together, these reviews indicate that (1) various forms of biofeedback are effective for migraine and tension-type headache; (2) outcomes with biofeedback rival outcomes with medication therapy; (3) combining biofeedback with medication can enhance outcomes; and (4) despite efficacy in many patients, biofeedback fails to bring significant relief to a sizeable number of headache patients. Biofeedback methods that more directly target headache pathophysiology have focused chiefly on migraine. These headache-specific approaches include blood volume pulse biofeedback, which has considerable supportive evidence, and electroencephalographic feedback.

Biofeedback has long been employed for helping ameliorate symptoms of recurrent headache; seminal work was performed in the late 1960s and first reported in the early 1970s.1,2 This early work focused mainly on electromyography (EMG) or muscle tension and hand temperature. Today a greater array of approaches are available, and they fall within two broad categories: (1) biofeedback-assisted relaxation and (2) specific or more specialized approaches.3

The first category employs the two types of biofeedback mentioned earlier (EMG and thermal feedback), as well as feedback on sweat gland activity, to counteract the sympathetic nervous arousal that occurs in response to stress for a host of disorders, not just headache. These types of biofeedback are commonly augmented with a variety of allied relaxation-based strategies (guided imagery, diaphragmatic or paced breathing, autogenic training, meditation, etc) as well as training in cognitive and behavioral stress coping. The second category takes a different approach, applying techniques that seek more directly to target the aberrant physiology underlying specific headache types. This latter category has focused chiefly on migraine headache and its variants.

This article reviews the supportive evidence for each category of biofeedback approaches to headache therapy and identifies select areas for future research attention.

EVIDENCE BASE FOR GENERAL BIOFEEDBACK TECHNIQUES IN HEADACHE

Biofeedback-assisted relaxation approaches for headache have been evaluated extensively over the past several decades. These evaluations have consisted of two basic types—comprehensive reviews by expert panels, and meta-analytic statistical analyses—as detailed below.

Expert panel reviews

A wide variety of groups have assessed biofeedback and related relaxation-based procedures by reviewing all relevant published studies according to rigorous pre-determined criteria. These groups include the National Institutes of Health, the Canadian Headache Society, the American Psychological Association, the Society of Pediatric Psychology, the Association for Applied Psycho physiology and Biofeedback, and the US Headache Consortium.

Meta-analytic reviews

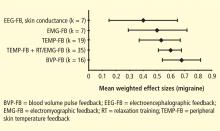

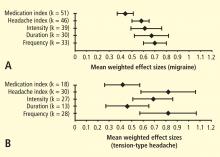

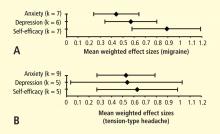

The other major type of evaluation applied to biofeedback for headache is more quantitative in nature, applying meta-analytical statistical analyses to available studies to determine the range and mean level of clinical effects across pooled studies. Biofeedback and related approaches to headache have been subject to an extensive number of quantitative reviews, the first being published in 1980.6 Since then, approximately 15 other quantitative reviews have compared behavioral treatments with one another, with various placebo conditions, or with various prophylactic medications for migraine and tension-type headaches in adults and in children and adolescents.7 The most recent meta-analysis, by Nestoriuc et al,8 focused extensively on biofeedback and will be discussed in detail here.

Nestoriuc et al identified and screened 150 clinical trials, including randomized controlled trials and quasi-experimental designs.8 Ninety-four of these trials met predefined inclusion criteria (headache diagnostic criteria specified, biofeedback evaluated as treatment alone or in combination with behavior therapy, outcome assessed using a structured headache diary, 5 or more patients per condition, and sufficient data to permit calculation of effect sizes). It was possible to include a sufficient number of studies to permit comparisons with two types of control groups: waiting list and placebo.