An overview of venous thromboembolism: Impact, risks, and issues in prophylaxis

ABSTRACTVenous thromboembolism (VTE) is a major cause of cardiovascular death, and its close association with increased age portends an increasing clinical and economic impact for VTE as the US population ages. Studies show that rates of VTE prophylaxis remain inadequate both in the hospital and at the time of discharge. Health care accreditation and quality organizations are taking interest in VTE risk assessment and prophylaxis as a measure for hospital performance ratings and even reimbursement. To set the stage for the rest of this supplement, this article reviews the rationale for VTE prophylaxis, surveys current prophylaxis rates and strategies to increase those rates, and provides an overview of risk factors for VTE and therapeutic options for VTE prophylaxis.

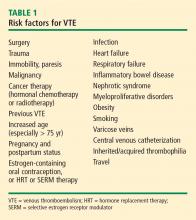

WHO’S AT RISK FOR VTE?

OPTIONS FOR VTE PROPHYLAXIS

An ideal therapy for VTE prophylaxis would be one that is effective, safe, inexpensive, and easy to administer and monitor, and that has few side effects or complications.

Mechanical prophylaxis

Mechanical forms of VTE prevention carry no risk of bleeding, are inexpensive because they can be reused, and are often effective when used properly. Mechanical forms include graduated compression stockings, intermittent pneumatic compression devices, and venous foot pumps.

The American College of Chest Physicians (ACCP), in its Seventh ACCP Conference on Antithrombotic and Thrombolytic Therapy, published in 2004,13 recommends that mechanical methods be used primarily in two settings:

- In patients with a high risk of bleeding (in whom pharmacologic prophylaxis is contraindicated)

- As an adjunct to pharmacologic prophylaxis.

Because the use of mechanical forms of prophylaxis in hospitalized medical patients is not evidence-based, mechanical prophylaxis should be reserved for those medical patients at risk for VTE who have a contraindication to pharmacologic prophylaxis.

To be effective, mechanical forms of prophylaxis must be used in accordance with the device manufacturer’s guidelines, which is frequently not what happens in clinical practice. In clinical trials in which the efficacy of intermittent pneumatic compression devices was demonstrated, patients wore their devices for 14 to 15 hours per day.

Pharmacologic options

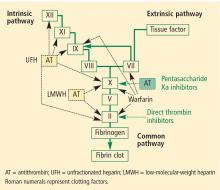

Unfractionated heparin (UFH) inhibits factor Xa and factor IIa equally. Because it is a large heterogeneous molecule, UFH is not well absorbed in subcutaneous tissue. Its anticoagulant response is variable because of its short half-life. It must be dosed two or three times daily subcutaneously for VTE prophylaxis, and must be given intravenously for treatment of VTE. The rate of heparin-induced thrombocytopenia, a potentially catastrophic adverse drug event, is considerably higher with UFH than with low-molecular-weight heparins (3% vs 1%).14 Osteopenia can develop with the use of UFH over even short periods, and osteoporosis can occur with long-term use.

Low-molecular-weight heparins (LMWHs) preferentially inhibit factor Xa compared to factor IIa. The LMWHs (ie, enoxaparin [Lovenox], dalteparin [Fragmin]) are derived from UFH through a chemical depolymerization and defractionation process that results in a much smaller molecule. LMWHs are well absorbed from subcutaneous tissue and have a predictable dose response attributable to their longer half-life (relative to UFH), which allows for once-daily or twice-daily subcutaneous dosing. As noted above, LMWHs carry a much lower rate of heparin-induced thrombocytopenia compared with UFH. Because LMWHs are predominantly cleared by the kidneys, dose adjustment may be needed in patients with renal impairment.

Fondaparinux (Arixtra) is a synthetic pentasaccha-ride that acts as a pure inhibitor of factor Xa. It binds antithrombin III, causing a conformational change by which it inhibits factor Xa and thereby inhibits coagulation further downstream. Fondaparinux has a long half-life (18 to 19 hours), which enables once-daily subcutaneous dosing but which also may require administration of the costly activated factor VII (NovoSeven) to reverse its effects in cases of bleeding. Because fondaparinux is cleared entirely by the kidneys, it is contraindicated in patients with severe renal impairment (creatinine clearance < 30 mL/min). It is also contraindicated in patients who weigh less than 50 kg, due to increased bleeding risk.

Details on the efficacy of these agents for VTE prophylaxis in various patient groups are provided in the subsequent articles in this supplement.

Investigational anticoagulants

The above pharmacologic options may soon be joined by several experimental anticoagulants that are currently in phase 3 trials for VTE prophylaxis—oral factor Xa inhibitors such as rivaroxaban and apixaban, and oral factor IIa (thrombin) inhibitors such as dabigatran.