Inflammation as a link between brain injury and heart damage: The model of subarachnoid hemorrhage*

ABSTRACT

Subarachnoid hemorrhage (SAH) serves as a good model for the study of heart-brain interactions because it is associated with both a high incidence of arrhythmia and a low prevalence of coronary heart disease. The pathophysiology of cardiac abnormalities in SAH is unsettled. Initial theories focused on sustained stimulation of cardiomyocytes at sympathetic nerve endings, but recent data suggest that dysfunction of the parasympathetic nervous system may contribute as well. We believe that the coupling of catecholamine release with parasympathetic dysfunction may allow unchecked inflammation that leads to myocardial dysfunction and cell death. We have developed a novel murine model of SAH to explore these potential inflammatory underpinnings of cardiac damage in SAH.

CARDIOMYOPATHY

Regional or focal wall-motion abnormalities on echocardiogram have been observed in some patients with SAH, as have increased levels of creatine kinase, MB fraction (CK-MB). These findings often raise concern about ongoing cardiac ischemia from coronary artery disease and may cause treatment to be delayed. In our experience, patients who have undergone cardiac catheterization for this syndrome have been found not have coronary artery disease as the cause of their cardiac muscle damage.

There is a common misperception among trainees at our institution that patients who have coronary artery disease with neurologic causes do not have elevations in cardiac enzymes. This turns out not to be the case. Cardiac troponin I (cTnI) has been shown to be a more sensitive and specific marker for cardiac dysfunction in patients with SAH than is CK-MB.

In a study of 43 patients with SAH and no known coronary artery disease, Deibert et al found that 12 patients (28%) had elevated cTnI.7 Abnormal left ventricular function was apparent on echocardiogram in 7 of these 12 patients. cTnI proved to be 100% sensitive and 86% specific for detecting left ventricular dysfunction in patients with SAH in this study, whereas CK-MB was only 29% sensitive and 100% specific. Notably, all patients in whom left ventricular dysfunction developed returned to baseline function on follow-up studies.

Similarly, Parekh et al found that cTnI is elevated in 20% of patients with SAH and that these patients are more likely to manifest echocardiographic and clinical evidence of left ventricular dysfunction.8 Patients with more severe grades of SAH in this study were more likely to develop an elevated level of serum cTnI.

PATHOPHYSIOLOGY OF CARDIAC DYSFUNCTION IN SUBARACHNOID HEMORRHAGE

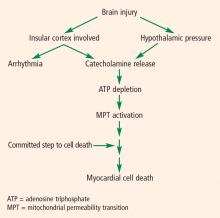

The pathophysiology of cardiac abnormalities in SAH is unsettled; one hypothesis that has support from human and experimental data proposes that sustained sympathetic stimulation of cardiomyocytes at the sympathetic nerve endings results in prolonged contraction and structural damage to the myocardium.5 Contraction band necrosis, a pathological pattern indicating that injury to the heart has occurred from muscles that have been energy-deprived from prolonged contraction, is a classic finding in autopsy specimens from patients with SAH. Transient low ejection fraction is the physiologic parameter that correlates with this pathologic finding.

We recently presented an interesting finding that may suggest complementary mechanisms of cardiac dysfunction.10 Twenty-nine consecutive patients with SAH and no record of preexisting coronary artery disease were enrolled in a study of ECG abnormalities in SAH at Alexandria University Hospitals in Egypt. Each patient had ECGs during the preoperative period, during surgery, and during the first 3 days of postoperative treatment. We found that patients who had ECG abnormalities that fluctuated over the course of their early treatment had worse outcomes. This finding suggests that part of the mechanism of cardiac damage may occur later than the initial ictus.

The area that our laboratory has actively pursued is the interaction between the sympathetic nervous system, the parasympathetic nervous system, and inflammation in cardiac damage after SAH. There are reasons to believe that dysfunction of the parasympathetic system may be involved in the pathology of cardiac damage. The next section explains the underpinnings of why we believe this avenue of research needs to be explored.

ROLE OF VAGAL ACTIVITY AND INFLAMMATION

In the body, the sympathetic and parasympathetic systems work as the yin and yang in controlling many bodily functions. Rate and rhythm control of the heart is the prime example. Until relatively recently, the cardiac muscle was thought to be innervated predominantly by the sympathetic system, with the parasympathetic system largely innervating the conduction system. Fibers from the vagus nerve are now known to innervate the myocardium and therefore may play a role in the cardiac damage in SAH.

The role of the vagal system in inflammation is described elsewhere in this proceedings supplement. Briefly, there exists a recent body of research on the role of the vagal system in modulating the inflammatory system through acetylcholine receptors.11 The “neuorinflammatory reflex” (a term coined by Tracey11) is a vagally mediated phenomenon that may relate to parasympathetic nervous system activation (debate continues over whether this is a parasympathetic function or a function of the vagus nerve that is not autonomic) that suppresses inflammation.

Evidence of parasympathetic dysfunction in SAH is becoming more abundant. Kawahara et al measured heart rate variability in patients with acute SAH and determined that enhanced parasympathetic activity occurs acutely.9 This acute activation could potentially contribute to ECG abnormalities and cardiac injury. In addition, the parasympathetic response may also affect the inflammatory response. It has long been known that cardiomyopathy in patients with SAH and other brain traumas is accompanied by inflammation. It is unclear whether the neutrophil infiltration seen in this cardiac damage is due to the primary response from the brain (and therefore possibly contributory) or is in reaction to the cardiac damage.

Evidence from the transplant literature

Support for the role of inflammation in cardiac damage following SAH comes from the cardiac transplant literature. Data indicate that the cause of death in an organ donor has an impact on the organ recipient’s course of transplantation. Tsai et al compared outcomes among 251 transplant recipients who received hearts from donors who died of atraumatic intracranial bleeding (group 1; n = 80) or from donors who died of other causes (group 2; n = 171).12 They found that mortality among transplant recipients was higher in group 1 (14%) than in group 2 (5%).

Yamani et al performed cardiac biopsies 1 week after transplantation and then performed serial coronary intravascular ultrasonography over 1 year in 40 patients, half of whom received hearts from donors who died from intracerebral hemorrhage (ICH) and half from donors who died from trauma.13 At 1 week, heart biopsies from the ICH group showed greater expression of matrix metalloproteinases, enzymes that are responsible for matrix remodeling and associated with proinflammatory states, compared with biopsies from the trauma group. The injury in the ICH group translated to an increase in vasculopathy and myocardial fibrosis. At 1 year, hearts from donors who died of trauma had much less fibrosis and less progression of coronary vasculopathy (as measured by change in maximal intimal thickness on intravascular ultrasonography) than did hearts from donors who died from ICH, even after correction for differences in age.

Yamani et al also found that mRNA expression of angiotensin II type 1 receptor (AT1R), which is upregulated during acute inflammation, was elevated 4.7-fold in biopsies of transplanted hearts from the donors who died of ICH compared with the donors who died of trauma.14 There was likewise a 2.6-fold increase in AT1R mRNA expression in spleen lymphocytes from donors who died of ICH compared with donors who died from trauma, indicating that systemic activation of inflammation occurred before transplantation.14 AT1R mRNA expression has also been found to be seven times greater in the cerebrospinal fluid of patients with SAH than in a control population (unpublished data). The fact that upregulation of an inflammatory mediator in the heart of transplant recipients is associated with ICH suggests that there is a potential for the cerebral injury–induced inflammation seen in Tracey’s sepsis model11 to affect the heart in a setting other than sepsis.