Trends in breast cancer screening and diagnosis

ABSTRACT

Screening mammography is the single most effective method of early breast cancer detection and is recommended on an annual basis beginning at age 40 for women at average risk of breast cancer. In addition to traditional film-screen mammograms, digital mammograms now offer digital enhancement to aid interpretation, which is especially helpful in women with dense breast tissue. Useful emerging adjuncts to mammography include ultrasonography, which is particularly helpful for further assessment of known areas of interest, and magnetic resonance imaging, which shows promise for use in high-risk populations. Image-guided biopsy directed by ultrasonograpy or stereotactic mammography views plays a critical role in histologic confirmation of suspected breast cancer.

DIAGNOSTIC MAMMOGRAPHY

Any mammography performed for a problem-solving purpose is considered diagnostic mammography (Table 2); the exam is tailored to the patient’s individual issue.25 Diagnostic mammography requires the presence of a qualified radiologist at the time of imaging. The goal is to come to a final conclusion about the mammographic or clinical finding at the time of the patient’s visit. Special views are usually performed that include, but are not limited to, spot-compression or spot-magnification views, depending on the finding.26 The patient is then given a same-day written account of the results at the conclusion of the study.

Examples of problems that may prompt diagnostic mammography include patient-reported palpable findings, screening mammography findings that are recalled for further investigation, or physician-detected findings. Often, ultrasonography is also used at the same visit and its results are integrated with the mammography findings to arrive at the final impression.

BREAST ULTRASONOGRAPHY AND BREAST MRI

Ultrasonography and MRI are two very useful adjunctive tools for breast lesion detection and analysis. At this time, however, neither is a replacement for screening mammography as a primary screening modality; rather, each is used in a complementary fashion for lesion analysis and biopsy guidance.10,27

Ultrasonography: Best for further study of areas of interest

Ultrasonography uses high-frequency sound waves to create a picture using a probe directed to an area of interest in the breast. The optimal probe for breast imaging is one typically operating in a frequency of 12 to 18 MHz and 4 cm in scanning width.

Because ultrasonography provides views of only a small area of breast tissue at a time, it is operator and patient dependent. It is best used when a known area of interest needs further evaluation, such as when a patient reports a palpable abnormality or when a mass is detected on mammography.

Ultrasonography uses no ionizing radiation, so it is especially helpful in young or pregnant women who present with a palpable abnormality. It is also useful for patients who have recently undergone a surgical procedure. As ultrasonography is currently used, no compression is needed and it can be performed easily in patients with limited mobility. Needle biopsies are most easily performed using ultrasonographic guidance.

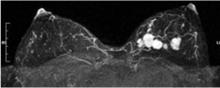

MRI: An emerging adjunct under study in high-risk patients

Breast MRI is an emerging modality under active research that shows promise for adjunctive breast imaging. It is commonly being used as a tool for local staging in women with newly diagnosed breast cancer.28,29 Current research is focused on its suitability as a screening modality, in conjunction with mammography, in high-risk populations based on family history and other factors addressed in the Gail model6 and similar risk models.

The limitations of breast MRI include its high cost, unsuitability for some patients (eg, the obese [due to table weight constraints], patients with pacemakers, patients with renal failure), the potential for unnecessary biopsies due to decreased specificity, lack of portability, and the length of time required for imaging.

When a lesion is initially detected with MRI, an attempt is usually made to identify it with ultrasonography as well, owing to the ease of ultrasonography-guided biopsy.32 It is important, however, for an imaging center that performs breast MRI to be able to perform biopsies using MRI guidance since not all lesions are identifiable by other modalities.33 Breast MRI studies are not easily portable between imaging facilities since a typical study contains a thousand or more images that are best viewed on a site-specific workstation monitor.

HISTOLOGIC CONFIRMATION

Once an abnormality is detected on imaging, a confirmatory histologic diagnosis is needed before embarking on medical or surgical treatments. Image-guided biopsy plays a critical role in this regard. In our breast imaging section, we perform ultrasonography-guided core needle biopsy and aspiration, stereotactic needle biopsy, and MRI-guided needle biopsy, as well as wire localizations on the day of surgery. All procedures performed are considered minimally invasive and are suitable for a vast majority of patients for whom they are recommended.34

Ultrasonography-guided procedures

Ultrasonography-guided fine-needle aspiration is an additional option for patients when core biopsy cannot be performed because the lesion is located adjacent to sensitive structures, such as implants or the pectoralis muscle. Fine-needle aspiration is also used to evaluate complicated breast cysts and, occasionally, lymph nodes. Drawbacks of fine-needle aspiration (relative to larger core needle biopsy) are that it is limited to cytologic, not histologic, examination and that it yields a higher false-negative rate.

Stereotactically guided procedures

Stereotactic core biopsy is performed when lesions—usually calcifications, but sometimes masses—are visible only on mammography.36,37 “Stereotactic” refers to the means by which the target is localized, ie, with a “stereo pair” of digital mammogram pictures with a small field of view. The patient is placed in a prone position with the breast of interest placed through a hole at the undersurface of the table in a light compression. The biopsy unit is attached to a dedicated computer that calculates coordinates. The needle is then brought to the coordinate position for sampling to take place.

The biopsy needle used for this procedure is vacuum-assisted, which means the needle is placed only one time, and samples in the vicinity of the target are vacuumed into a reservoir for retrieval. If the target is calcifications, a specimen radiograph is routinely performed to verify adequate sample acquisition before the patient leaves the biopsy table.38 When the original target is no longer visible, a titanium marker clip is often placed. This facilitates localization of the biopsied area should surgery be needed.

Stereotactic biopsy has several limitations that ultrasonography-guided biopsy does not. The patient must be cooperative and mobile enough to get on the table and hold a prone position for the duration of the procedure (about 45 minutes). If the patient is taking warfarin or has a bleeding diathesis, preprocedure steps such as clinical evaluation to check the international normalized ratio and prothrombin time, or even stopping the warfarin temporarily, may be needed to minimize bleeding during the procedure, as a 9- or 12-gauge needle is used. Stereotactic biopsy is also limited by lesion position. A far posterior lesion may not be accessible if it does not reach through the hole in the table. Also, there is a limit to the compressed thinness of breast tissue that can be biopsied. Finally, most tables used for stereotactic biopsy have a functioning weight limit of 300 pounds.

Open surgical biopsy

A final option is open surgical biopsy, which is used when the more minimally invasive techniques are equivocal, discordant, or impossible due to the limitations noted above, or when atypical cells are found.

HOW SHOULD WE SCREEN OUR PATIENTS?

The various screening options for breast cancer are listed in Table 4, along with their market approval status and Medicare reimbursement levels.

For women at average risk for breast cancer, the American Cancer Society recommends an annual mammogram and clinical breast examination by a physician beginning at age 40 (Table 1).10

In conclusion, the process of finding breast cancer includes regular screening with mammography and clinical breast examination (plus MRI in high-risk women) and the diagnostic modalities of ultrasonography, MRI, and diagnostic mammography. Our ultimate goal is to find cancer at the earliest time possible by all means necessary for the individual patient.