Trends in breast cancer screening and diagnosis

ABSTRACT

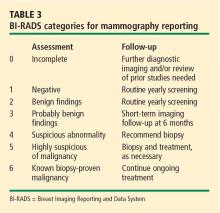

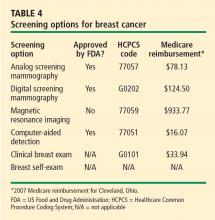

Screening mammography is the single most effective method of early breast cancer detection and is recommended on an annual basis beginning at age 40 for women at average risk of breast cancer. In addition to traditional film-screen mammograms, digital mammograms now offer digital enhancement to aid interpretation, which is especially helpful in women with dense breast tissue. Useful emerging adjuncts to mammography include ultrasonography, which is particularly helpful for further assessment of known areas of interest, and magnetic resonance imaging, which shows promise for use in high-risk populations. Image-guided biopsy directed by ultrasonograpy or stereotactic mammography views plays a critical role in histologic confirmation of suspected breast cancer.

A WORD ABOUT BREAST EXAMINATION

Breast self-examination

Clinical breast examination

As noted in Table 1, regular clinical breast examinations are recommended by the American Cancer Society for asymptomatic women at average risk for breast cancer, with the recommended frequency depending on the woman’s age.10 The US Preventive Services Task Force takes the stance that there is insufficient evidence to recommend for or against breast cancer screening with clinical breast examination alone.11 While it is unclear precisely what contribution clinical breast exams make to the detection of breast cancer, they certainly provide clinicians an opportunity to raise awareness about breast cancer and educate patients about breast symptoms, risk factors, and new detection technologies.10

SCREENING MAMMOGRAPHY

Screening mammography is the single most effective method of early breast cancer detection,1 and the American Cancer Society recommends that women at average risk for breast cancer have annual screening mammograms beginning at age 40 years (Table 1).10

The evidence base

The primary evidence supporting the recommendation for screening mammography comes from eight randomized trials that studied the effectiveness of screening mammography for cancer detection in Sweden,12,13 the United States,14 Canada,15,16 and the United Kingdom.17 Overall, breast cancers detected by screening mammography are smaller and have a more favorable history and tumor biology than those detected clinically without the use of imaging. A pooled analysis of the most recent data from all randomized trials of screening mammography in women aged 39 to 74 years showed a 24% reduction in mortality (95% CI, 18% to 30%) in women undergoing screening mammography, although not all individual trials showed a statistically significant mortality reduction.10

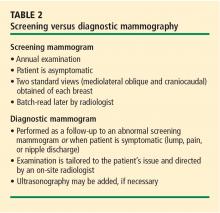

The screening procedure at a glance

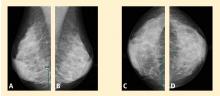

Analog vs digital

Digital mammograms are radiographs that are acquired digitally and allow digital enhancement to aid in interpretation. When receiving a digital mammogram, the woman being screened still undergoes compression and positioning as for a conventional film-screen mammogram, and the images are still produced with x-rays. However, digitization allows manipulation of the images as they are being interpreted, enabling the radiologist to focus on areas of interest or to “window” and “level” the image, similar to adjusting the tint and contrast on a television set.

Research trials comparing digital and film mammography, such as the Digital Mammographic Imaging Screening Trial (DMIST),19 have found digital mammography to be especially helpful in women with extremely dense breasts, who have an elevated risk for breast cancer. For women with fatty breasts the differences between the types of mammogram are less significant.

For further detail on digital mammography, readers are referred to the recent review by D’Orsi and Newell.20

SCREENING THE SURGICALLY ALTERED BREAST

Following surgical cancer treatment or reconstructive surgery, screening of remaining breast tissue for cancer is still performed and is just as essential to patient care as presurgery screening. The first line of defense for any patient with a surgically altered breast is mammography.

When a patient has had breast reconstruction following mastectomy, it is presumed that very little breast tissue remains. There is no standard of care for screening the nonbreast tissue introduced by the reconstructive procedure. Nonetheless, at our institution we perform a single mediolateral oblique projection on any flap-reconstructed breast in light of rare anecdotal accounts of cancer found in and around the reconstructed breast. When problem-solving is needed to evaluate a new palpable abnormality, special angled views (tangential) and directed ultrasonography can be used. We do not routinely perform screening mammography on mastectomy patients who have had reconstruction with implants, but we can investigate areas of clinical concern (eg, due to palpable masses) with directed ultrasonography.21

The cosmetically altered breast presents its own issues in cancer detection. Both silicone-gel and saline implants obscure breast tissue that could contain cancer. For this reason, special implant-displaced views are performed that allow visualization of a larger portion of breast tissue beyond that allowed by standard mammograms. Therefore, an asymptomatic patient with implants who presents for screening mammography will have eight mammography views obtained instead of the routine four views.22

Patients who have had breast reduction, excisional biopsy, or prior breast conservation surgery (lumpectomy and radiation) are screened in a routine manner with mammography.23 Patients who have had prior surgical procedures often have architectural distortion at the surgical site, which is generally stable over time. Any prior surgical procedure can predispose the patient to the development of fat necrosis, which is a benign entity but can mimic cancer in its early phases through the development of calcifications and, occasionally, a new palpable lump. We most commonly confront this issue in the period 2 to 4 years after the operation.24 Occasionally the findings are such that a biopsy is needed to determine whether fat necrosis is the cause. In this population, magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) can also be used as an adjunctive tool, and can sometimes clarify the presence of fat necrosis and other postoperative findings, such as seroma, hematoma, or inflammation. In other instances, only a biopsy can determine what a particular finding represents.