Myopathy for the general internist: Statins and much more

ABSTRACT

Patients with muscle diseases are often seen initially by general practitioners. This article reviews how to evaluate and manage such patients, including those taking a statin, how to interpret creatine kinase (CK) test results, and how to recognize common as well as potentially dangerous myopathies.

KEY POINTS

- Inclusion body myositis affects older men more than women and is characterized by slowly progressive, asymmetric, distal and proximal weakness and atrophy.

- Statin-associated muscle complaints are common, whereas necrotizing myopathy, characterized by a very high CK plus weakness, is rare but must be recognized.

- Elevated CK does not necessarily indicate myositis, especially in African Americans or after heavy exercise.

- Dermatomyositis is characterized by muscle weakness and raised red or purple Gottron papules over the knuckles, elbows, or knees.

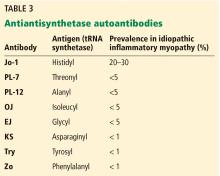

- Autoimmune interstitial lung disease may be caused by a variety of antibodies, the most common being anti-Jo-1 (directed against histidyl tRNA synthetase).

- The rarer non-Jo-1 antisynthetase autoantibodies may be associated with rapidly progressive interstitial lung disease, which is a challenge to recognize because associated rheumatologic symptoms may be minimal.

Autoantibody defines subgroup of necrotizing myopathy

Also in 2010, Christopher-Stine et al14 reported an antibody associated with necrotizing myopathy. Of 38 patients with the condition, 16 were found to have an abnormal “doublet” autoantibody recognizing 200- and 100-kDa proteins. All patients had weakness and a high CK level, and 63% had statin exposure before the weakness (this percentage increased to 83% in patients older than 50). All responded to immunosuppressive therapy, and many had a relapse when it was withdrawn.

Statins lower cholesterol by inhibiting 3-hydroxy-3-methylglutaryl-Co A reductase (HMGCR), and paradoxically, they also upregulate it. HMGCR has a molecular weight of 97 kDa. Mammen et al15 identified HMGCR as the 100-kDa target of the identified antibody and developed an enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay for it. Of 750 patients presenting to one center, only 45 (6%) had anti-HMGCR autoantibodies, but all 16 patients who had the abnormal doublet antibody tested positive for anti-HMGCR. Regenerating muscle cells express high levels of HMGCR, which may sustain the immune response after statins are discontinued.

Case 3 continued: Intravenous immunoglobulin brings improvement

In March 2010, when the 67-year-old patient presented to our myositis center, her CK level was 5,800 U/L, which increased as prednisone was tapered. She still felt weak. On examination, her muscle strength findings were deltoids 4+/5, neck flexors 4/5, and iliopsoas 3+/5. She was treated with methotrexate and azathioprine without benefit. She was next treated with intravenous immunoglobulin, and after 3 months, her strength normalized for the first time in years. Her CK level decreased but did not normalize. Testing showed that she was positive for anti-HMGCR autoantibody, as this test had become commercially available.

In 2015, Mammen and Tiniakou16 suggested using intravenous immunoglobulin as first-line therapy for statin-associated autoimmune necrotizing myopathy, based on experience at a single center with 3 patients who declined glucocorticoid treatment.

Necrotizing myopathy: Bottom line

Myositis overlap syndromes

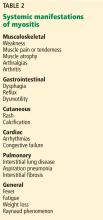

Heterogeneity is the rule in myositis, and it can present with a wide variety of signs and symptoms as outlined in Table 2.

CASE 4: FEVER, NEW ‘RHEUMATOID ARTHRITIS,’ AND LUNG DISEASE

A 52-year-old woman with knee osteoarthritis saw her primary care physician in November 2013 for dyspnea and low-grade fever. The next month, she presented with polyarthritis, muscle weakness, and Raynaud phenomenon.

In January 2014, she developed acrocyanosis of her fingers. Examination revealed hyperkeratotic, cracked areas of her fingers. Her oxygen saturation by pulse oximetry was low. She was admitted to the hospital. Her doctor suspected new onset of rheumatoid arthritis, but blood tests revealed a negative antinuclear antibody, so an autoimmune condition was deemed unlikely. Her CK was mildly elevated at 350 U/L.

Because of her dyspnea, an open-lung biopsy was performed. High-resolution computed tomography (CT) revealed infiltrates and ground-glass opacities, leading to the diagnosis of nonspecific interstitial pneumonia. A rheumatologist was consulted and recommended pulse methylprednisolone, followed by prednisone 60 mg/day and mycophenolate mofetil. Testing for Jo-1 antibodies was positive.

Antisynthetase syndrome

The antisynthetase syndrome is a clinically heterogeneous condition that can occur with any or all of the following:

- Fever

- Myositis

- Arthritis (often misdiagnosed as rheumatoid arthritis)

- Raynaud phenomenon

- Mechanic’s hands (hyperkeratotic roughness with fissures on the lateral aspects of the fingers and finger pads)

- Interstitial lung disease.

The skin rashes and myositis may be subtle, making the presentation “lung-dominant,” and nonrheumatologists should be aware of this syndrome. Although in our patient the condition developed in a classic manner, with all of the aforementioned features of the antisynthetase syndrome, some patients will manifest one or a few of the features.

Clinically, patients with the Jo-1 antisynthetase syndrome often present differently than those with non-Jo-1 antisynthetase autoantibodies. When we compared 122 patients with Jo-1 vs 80 patients with a non-Jo-1 antisynthetase autoantibody, patients with Jo-1 antibodies were more likely to have initially received a diagnosis of myositis (83%), while myositis was the original diagnosis in only 17% of those possessing non-Jo-1 antisynthetase autoantibodies. In fact, many patients (approximately 50%) were diagnosed as having undifferentiated connective tissue disease or an overlap syndrome, and 13% had scleroderma as their first diagnosis.17

We also found that the survival rate was higher in patients with Jo-1 syndrome compared with patients with non-Jo-1 antisynthetase syndromes. We attributed the difference in survival rates to a delayed diagnosis in the non-Jo-1 group, perhaps due to their “nonclassic” presentations of the antisynthetase syndrome, delaying appropriate treatment. Patients received a diagnosis of Jo-1 antibody syndrome after a mean of 0.4 year (range 0.2–0.8), while those with a non-Jo-1 antisynthetase autoantibody had a delay in diagnosis of 1.0 year (range 0.4–5.1) (P < .01).17

In nearly half the cases in this cohort, pulmonary fibrosis was the cause of death, with primary pulmonary hypertension being the second leading cause (11%).

Antisynthetase syndrome: Bottom line

Antisynthetase syndrome is an often fatal disease that does not always present in a typical fashion with symptoms of myositis, as lung disease may be the predominant feature. A negative antinuclear antibody test result does not imply antibody negativity, as the autoantigen in these diseases is not located in the nucleus. Prompt diagnosis and appropriate immunosuppressive therapy are critical to improving outcomes.