Myopathy for the general internist: Statins and much more

ABSTRACT

Patients with muscle diseases are often seen initially by general practitioners. This article reviews how to evaluate and manage such patients, including those taking a statin, how to interpret creatine kinase (CK) test results, and how to recognize common as well as potentially dangerous myopathies.

KEY POINTS

- Inclusion body myositis affects older men more than women and is characterized by slowly progressive, asymmetric, distal and proximal weakness and atrophy.

- Statin-associated muscle complaints are common, whereas necrotizing myopathy, characterized by a very high CK plus weakness, is rare but must be recognized.

- Elevated CK does not necessarily indicate myositis, especially in African Americans or after heavy exercise.

- Dermatomyositis is characterized by muscle weakness and raised red or purple Gottron papules over the knuckles, elbows, or knees.

- Autoimmune interstitial lung disease may be caused by a variety of antibodies, the most common being anti-Jo-1 (directed against histidyl tRNA synthetase).

- The rarer non-Jo-1 antisynthetase autoantibodies may be associated with rapidly progressive interstitial lung disease, which is a challenge to recognize because associated rheumatologic symptoms may be minimal.

CLASSIFYING MYOSITIS

Myositis (idiopathic inflammatory myopathy) is a heterogeneous group of autoimmune syndromes of unknown cause characterized by chronic muscle weakness and inflammation of striated muscle. These syndromes likely arise as a result of genetic predisposition and an environmental or infectious “hit.”

Myositis is rare, with an incidence of 5 to 10 cases per million per year and an estimated prevalence of 50 to 90 cases per million. It has 2 incidence peaks: 1 in childhood (age 5–15) and another in adult midlife (age 30–50). Women are affected 2 to 3 times more often than men, with black women most commonly affected.

Myositis is traditionally classified as follows:

- Adult polymyositis

- Adult dermatomyositis

- Juvenile myositis (dermatomyositis much more frequent than polymyositis)

- Malignancy-associated myositis (usually dermatomyositis)

- Myositis overlapping with another autoimmune disease

- Inclusion body myositis.

However, polymyositis is less common than we originally thought, and the term necrotizing myopathy is now used in many patients, as noted in the case studies below. Further, myositis overlap syndromes are being increasingly diagnosed, likely related to the emergence of autoantibodies and clinical “syndromes” associated with these autoantibody subsets (discussed in cases below).

Dermatomyositis

Dermatomyositis is characterized by muscle weakness and a rash that can be obvious or subtle. Classic skin lesions are Gottron papules, which are raised, flat-topped red or purplish lesions over the knuckles, elbows, or knees.

Lesions may be confused with those of psoriasis. There can also be a V-neck rash over the anterior chest or upper back (“shawl sign”) or a rash over the lateral thigh (“holster sign”). A facial rash may occur, but unlike lupus, dermatomyositis does not spare the nasolabial area. However, the V-neck rash can be similar to that seen in lupus.

Dermatomyositis may cause muscle pain, perhaps related to muscle ischemia, whereas polymyositis and necrotizing myopathy are often painless. However, pain is also associated with fibromyalgia, which may be seen in many autoimmune conditions. It is important not to overtreat rheumatologic diseases with immunosuppression to try to control pain if the pain is actually caused by fibromyalgia.

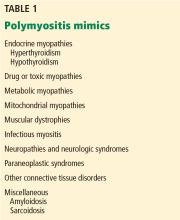

Polymyositis mimics

Hypothyroid myopathy can present as classic polymyositis. The serum CK may be elevated, and there may be myalgias, muscle hypertrophy with stiffness, weakness, cramps, and even features of a proximal myopathy, and rhabdomyolysis. The electromyogram can be normal or myopathic. Results of muscle biopsy are often normal but may show focal necrosis and mild inflammatory infiltrates, thus mimicking that seen with inflammatory myopathy.7

Drug-induced or toxic myopathies can also mimic polymyositis. Statins are among the most commonly prescribed drugs in the United States, with more than 35 million people taking them. Statins are generally well tolerated but have a broad spectrum of toxicity, ranging from myalgias to life-threatening rhabdomyolysis. Myalgias lead to about 5% to 10% of patients refusing to take a statin or stopping it on their own.

Myalgias affect up to 20% of statin users in clinical practice.8,9 A small cross-sectional study10 of 1,000 patients in a primary care setting found that the risk of muscle complaints in statin users was 1.5 times higher than in nonstatin users, similar to findings in other studies.

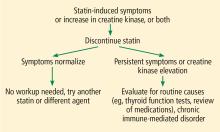

My strategy for managing a patient with possible statin-induced myopathy is illustrated in Figure 1.

CASE 3: WEAKNESS, VERY HIGH CK ON A STATIN

In March 2010, a 67-year-old woman presented with muscle weakness. She had a history of hypertension, hyperlipidemia, and, more than 10 years previously, uterine cancer. In 2004, she was given atorvastatin for dyslipidemia. Four years later, she developed lower-extremity weakness, which her doctor attributed to normal aging. A year after that, she found it difficult to walk up steps and lift her arms overhead. In June 2009, she stopped taking the atorvastatin on her own, but the weakness did not improve.

In September 2009, she returned to her doctor, who found her CK level was 6,473 U/L but believed it to be an error, so the test was repeated, with a result of 9,375 U/L. She had no rash or joint involvement.

She was admitted to the hospital and underwent muscle biopsy, which showed myonecrosis with no inflammation or vasculitis. She was treated with prednisone 60 mg/day, and her elevated CK level and weakness improved.

Immune-mediated necrotizing myopathy associated with statins

The hallmark of necrotizing myopathy is myonecrosis without significant inflammation.12 This pattern contrasts with that of polymyositis, which is characterized by lymphocytic inflammation.

Although statins became available in the United States in 1987, immune-mediated necrotizing myopathy associated with statins was first described only in 2010. In that report, Grable-Esposito et al13 described 25 patients from 2 neuromuscular centers seen between 2000 and 2008 who had elevated CK and proximal weakness during or after statin use, both of which persisted despite stopping the statin. Patients improved with immunosuppressive agents but had a relapse when steroids were stopped or tapered, a pattern typical in autoimmune disease.