An unusual cause of bruising

Release date: August 1, 2019

Expiration date: July 31, 2020

Estimated time of completion: 1 hour

Click here to start this CME/MOC activity.

CASE CONTINUED: TREATMENT, LYMPHOCYTOSIS

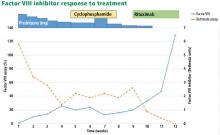

The patient was started on 60 mg daily of prednisone, resulting in a decrease in her aPTT, increase in factor VIII level, and lower Bethesda titer. On a return visit, her absolute lymphocyte count was 7.04 × 109/L (reference range 1.0–4.0). She reported no fevers, chills, or recent infections.

EVALUATING LYMPHOCYTOSIS

Lymphocytosis is defined in most laboratories as an absolute lymphocyte count greater than 4.0 × 109/L for adults. Normally, T cells (CD3+) make up 60% to 80% of lymphocytes, B cells (CD20+) 10% to 20%, and natural killer (NK) cells (CD3–, CD56+) 5% to 10%. Lymphocytosis is usually caused by infection, but it can have other causes, including malignancy.

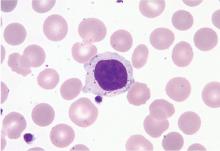

Peripheral blood smear. If there is no clear cause of lymphocytosis, a peripheral blood smear can be used to assess lymphocyte morphology, providing clues to the underlying etiology. For example, atypical lymphocytes are often seen in infectious mononucleosis, while “smudge” lymphocytes are characteristic of chronic lymphocytic leukemia. If a peripheral smear shows abnormal morphology, further workup should include establishing whether the lymphocytes are polyclonal or clonal.8

,CASE CONTINUED: LARGE GRANULAR LYMPHOCYTES

4. What is the next step to evaluate the patient’s lymphocytosis?

- Bone marrow biopsy

- Karyotype analysis

- Flow cytometry

- Fluorescence in situ hybridization

Flow cytometry with V-beta analysis is the best first test to determine the cause of lymphocytosis after review of the peripheral smear. For persistent lymphocytosis, flow cytometry should be done even if a peripheral smear shows normal lymphocyte morphology.

Most T cells possess receptors composed of alpha and beta chains, each encoded by variable (V), diversity (D), joining (J), and constant (C) gene segments. The V, D, and J segments undergo rearrangement during T-cell development in the thymus based on antigen exposure, producing a diverse T-cell receptor population.

In a polyclonal population of lymphocytes, the T-cell receptors have a variety of gene segment arrangements, indicating normal T-cell development. But in a clonal population of lymphocytes, the T-cell receptors have a single identical gene segment arrangement, indicating they all originated from a single clone.9 Lymphocytosis in response to an infection is typically polyclonal, while malignant lymphocytosis is clonal.

Monoclonal antibodies against many of the variable regions of the beta chain (V-beta) of T-cell receptors have been developed, enabling flow cytometry to establish clonality.

T-cell receptor gene rearrangement studies can also be performed using polymerase chain reaction and Southern blot techniques.9

Karyotype analysis is usually not performed for the finding of LGLs, because most leukemias (eg, T-cell and NK-cell leukemias) have cells with a normal karyotype.

Bone marrow biopsy is invasive and usually not required to evaluate LGLs. It can be especially risky for a patient with a bleeding disorder such as a factor VIII inhibitor.10

Case continued: Flow cytometry confirms clonality

Subsequent flow cytometry found that more than 50% of the patient’s lymphocytes were LGLs that co-expressed CD3+, CD8+, CD56+, and CD57+, with aberrantly decreased CD7 expression. T-cell V-beta analysis demonstrated an expansion of the V-beta 17 family, and T-cell receptor gene analysis with polymerase chain reaction confirmed the presence of a clonal rearrangement.

LGL LEUKEMIA: CLASSIFICATION AND MANAGEMENT

LGLs normally account for 10% to 15% of peripheral mononuclear cells.11 LGL leukemia is caused by a clonal population of cytotoxic T cells or NK cells and involves an increased number of LGLs (usually > 2 × 109/L).10

LGL leukemia is divided into 3 categories according to the most recent World Health Organization classification10,12:

T-cell LGL leukemia (about 85% of cases) is considered indolent but can cause significant cytopenias and is often associated with autoimmune disease.13 Cells usually express a CD3+, CD8+, CD16+, and CD57+ phenotype. Survival is about 70% at 10 years.

Chronic NK-cell lymphocytosis (about 10%) also tends to have an indolent course with cytopenia and an autoimmune association, and with a similar prognosis to T-cell LGL leukemia. Cells express a CD3–, CD16+, and CD56+ phenotype.

Aggressive NK-cell LGL leukemia (about 5%) is associated with Epstein-Barr virus infection and occurs in younger patients. It is characterized by severe cytopenias, “B symptoms” (ie, fever, night sweats, weight loss), and has a very poor prognosis. Like chronic NK-cell lymphocytosis, cells express a CD3–, CD16+, and CD56+ phenotype. Fas (CD95) and Fas-ligand (CD178) are strongly expressed.10,13

Most cases of LGL leukemia can be diagnosed on the basis of classic morphology on peripheral blood smear and evidence of clonality on flow cytometry or gene rearrangement studies. T-cell receptor gene studies cannot be used to establish clonality in the NK subtypes, as NK cells do not express T-cell receptors.11

Case continued: Diagnosis, continued course

In our patient, T-cell LGL leukemia was diagnosed on the basis of the peripheral smear, flow cytometry results, and positive T-cell receptor gene studies for clonal rearrangement in the T-cell receptor beta region.

While her corticosteroid therapy was being tapered, her factor III inhibitor level increased, and she had a small episode of bleeding, prompting the start of cyclophosphamide 50 mg daily with lower doses of prednisone.