An unusual cause of bruising

Release date: August 1, 2019

Expiration date: July 31, 2020

Estimated time of completion: 1 hour

Click here to start this CME/MOC activity.

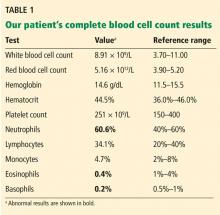

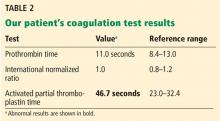

A 61-year-old woman presented to our hematology clinic for evaluation of multiple episodes of bruising. The first episode occurred 8 months earlier, when she developed a large bruise after water skiing. Two months before coming to us, she went to her local emergency room because of new bruising and was found to have a prolonged activated partial thromboplastin time (aPTT) of 60 seconds (reference range 23.3–34.9), but she underwent no further testing at that time.

At presentation to our clinic, she reported having no fevers, night sweats, unintentional weight loss, swollen lymph nodes, joint pain, rashes, mouth sores, nosebleeds, or blood in the urine or stool. Her history was notable only for hypothyroidism, which was diagnosed in the previous year. Her medications included levothyroxine, vitamin D3, and vitamin C. She had been taking a baby aspirin daily for the past 10 years but had stopped 1 month earlier because of the bruising.

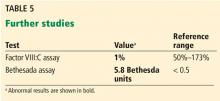

Ten years earlier she had been evaluated for a possible transient ischemic attack; laboratory results at that time included a normal aPTT of 25.1 seconds and a normal factor VIII level of 153% (reference range 50%–173%).

EVALUATION FOR AN ISOLATED PROLONGED aPTT

1. What is the appropriate next test to evaluate this patient’s prolonged aPTT?

- Lupus anticoagulant panel

- Coagulation factor levels

- Mixing studies

- Bethesda assay

Mixing studies

Once a prolonged aPTT is confirmed, the appropriate next step is a mixing study. This involves mixing the patient’s plasma with pooled normal plasma in a 1-to-1 ratio, then repeating the aPTT test immediately, and again after 1 hour of incubation at 37°C. If the patient does not have enough of one of the coagulation factors, the aPTT immediately returns to the normal range when plasma is mixed with the pooled plasma because the pooled plasma contains the factor that is lacking. If this happens, then factor assays should be performed to identify the deficient factor.1

Various antibodies that inhibit coagulation factors can also affect the aPTT. There are 2 general types: immediate-acting and delayed.

With an immediate-acting inhibitor, the aPTT does not correct into the normal range with initial mixing. Immediate-acting inhibitors are often seen together with lupus anticoagulants, which are nonspecific phospholipid antibodies. If an immediate-acting inhibitor is detected, further testing should focus on evaluation for lupus anticoagulant, including phospholipid-dependency studies.

With a delayed inhibitor, the aPTT initially comes down, but subsequently goes back up after incubation. Acquired factor VIII inhibitor is a classic delayed-type inhibitor and is also the most common factor inhibitor.1 If a delayed-acting inhibitor is found, specific intrinsic factor levels should be measured (factors VIII, IX, XI, and XII),2 and testing should also be done for lupus anticoagulant, as these inhibitors may occur together.