Heart failure guidelines: What you need to know about the 2017 focused update

Release date: February 1, 2019

Expiration date: January 31, 2020

Estimated time of completion: 1 hour

Click here to start this CME/MOC activity.

ABSTRACT

The 2017 focused update of the 2013 ACC/AHA guideline on heart failure contains new and important recommendations on prevention, novel biomarker uses, heart failure with preserved ejection fraction (HFpEF), and comorbidities such as hypertension, iron deficiency, and sleep-disordered breathing. Potential implications for management of acute decompensated heart failure will also be explored.

KEY POINTS

- Despite advances in treatment, heart failure remains highly morbid, common, and costly. Prevention is key.

- Strategies to prevent progression to clinical heart failure in high-risk patients include new blood pressure targets (< 130/80 mm Hg) and B-type natriuretic peptide screening to prompt referral to a cardiovascular specialist.

- An aldosterone receptor antagonist might be considered to decrease hospitalizations in appropriately selected stage C HFpEF patients. Routine use of nitrates or phosphodiesterase-5 inhibitors in such patients is not recommended.

- Outpatient intravenous iron infusions are reasonable in persistently symptomatic New York Heart Association stage II to III heart failure with reduced ejection fraction (HFrEF) to improve functional capacity and quality of life.

- The new systolic blood pressure target is less than 130 mm Hg for stage A heart failure, stage C HFrEF, and stage C HFpEF.

The PRIME-HF trial

The Predischarge Initiation of Ivabradine in the Management of Heart Failure (PRIME-HF) trial69 is a randomized, open-label, multicenter trial comparing standard care vs the initiation of ivabradine before discharge, but after clinical stabilization, during admissions for ADHF in patients with chronic HFrEF (left ventricular ejection fraction ≤ 35%). At subsequent outpatient visits, the dosage can be modified in the ivabradine group, or ivabradine can be initiated at the provider’s discretion in the usual-care group.

PRIME-HF is attempting to determine whether initiating ivabradine before discharge will result in more patients taking ivabradine at 180 days, its primary end point, as well as in changes in secondary end points including heart rate and patient-centered outcomes. The study is active, with reporting expected in 2019.

As these trials all come to completion, it will not be long before we have further guidance regarding the inpatient initiation of these new and exciting therapeutic agents.

,SHOULD INTRAVENOUS IRON BE GIVEN DURING ADHF ADMISSIONS?

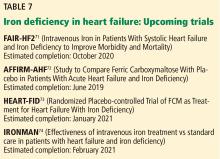

Given the high prevalence of iron deficiency in symptomatic HFrEF, its independent association with mortality, improvements in quality of life and functional capacity suggested by repleting with intravenous iron (in FAIR-HF and CONFIRM-HF), the seeming inefficacy of oral iron in IRONOUT, and the logistical challenges of intravenous administration during standard clinic visits, could giving intravenous iron soon be incorporated into admissions for ADHF?

Caution has been advised for several reasons. As discussed above, larger randomized controlled trials powered to detect more definitive clinical end points such as death and the rate of hospitalization are still needed before a stronger recommendation can be made for intravenous iron in HFrEF. Also, without such data, it seems unwise to add the considerable economic burden of routinely assessing for iron deficiency and providing intravenous iron during ADHF admissions to the already staggering costs of heart failure.

The effects seen on morbidity and mortality that become evident in these trials over the next 5 years will help determine future guidelines and whether intravenous iron is routinely administered in bridge clinics, during inpatient admissions for ADHF, or not at all in patients with HFrEF and iron deficiency.

INTERNISTS ARE KEY

Heart failure remains one of the most common, morbid, complex, and costly diseases in the United States, and its prevalence is expected only to increase.4,5 The 2017 update1 of the 2013 guideline2 for the management of heart failure provides recommendations aimed not only at management of heart failure, but also at its comorbidities and, for the first time ever, at its prevention.

Internists provide care for the majority of heart failure patients, as well as for their comorbidities, and are most often the first to come into contact with patients at high risk of developing heart failure. Thus, a thorough understanding of these guidelines and how to apply them to the management of acute decompensated heart failure is of critical importance.