Heart failure guidelines: What you need to know about the 2017 focused update

Release date: February 1, 2019

Expiration date: January 31, 2020

Estimated time of completion: 1 hour

Click here to start this CME/MOC activity.

ABSTRACT

The 2017 focused update of the 2013 ACC/AHA guideline on heart failure contains new and important recommendations on prevention, novel biomarker uses, heart failure with preserved ejection fraction (HFpEF), and comorbidities such as hypertension, iron deficiency, and sleep-disordered breathing. Potential implications for management of acute decompensated heart failure will also be explored.

KEY POINTS

- Despite advances in treatment, heart failure remains highly morbid, common, and costly. Prevention is key.

- Strategies to prevent progression to clinical heart failure in high-risk patients include new blood pressure targets (< 130/80 mm Hg) and B-type natriuretic peptide screening to prompt referral to a cardiovascular specialist.

- An aldosterone receptor antagonist might be considered to decrease hospitalizations in appropriately selected stage C HFpEF patients. Routine use of nitrates or phosphodiesterase-5 inhibitors in such patients is not recommended.

- Outpatient intravenous iron infusions are reasonable in persistently symptomatic New York Heart Association stage II to III heart failure with reduced ejection fraction (HFrEF) to improve functional capacity and quality of life.

- The new systolic blood pressure target is less than 130 mm Hg for stage A heart failure, stage C HFrEF, and stage C HFpEF.

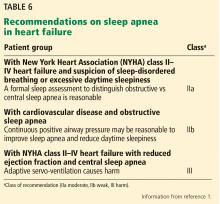

New or modified recommendations on sleep-disordered breathing

Given the common association with heart failure (60%)45 and the marked variation in response to treatment, including potential for harm with adaptive servo-ventilation and central sleep apnea, a class IIa recommendation is made stating that it is reasonable to obtain a formal sleep study in any patient with symptomatic (NYHA class II–IV) heart failure.1

Due to the potential for harm with adaptive servo-ventilation in patients with central sleep apnea and NYHA class II to IV HFrEF, a class III (harm) recommendation is made against its use.

,Largely based on the results of the Sleep Apnea Cardiovascular Endpoints (SAVE) trial,56 a class IIb, level of evidence B-R (moderate, based on randomized trials) recommendation is given, stating that the use of CPAP in those with OSA and known cardiovascular disease may be reasonable to improve sleep quality and reduce daytime sleepiness.

POTENTIAL APPLICATIONS IN ACUTE DECOMPENSATED HEART FAILURE

Although the 2017 update1 is directed mostly toward managing chronic heart failure, it is worth considering how it might apply to the management of ADHF.

SHOULD WE USE BIOMARFER TARGETS TO GUIDE THERAPY IN ADHF?

The 2017 update1 does offer direct recommendations regarding the use of biomarker levels during admissions for ADHF. Mainly, they emphasize that the admission biomarker levels provide valuable information regarding acute prognosis and risk stratification (class I recommendation), while natriuretic peptide levels just before discharge provide the same for the postdischarge timeframe (class IIa recommendation).

The update also explicitly cautions against using a natriuretic peptide level-guided treatment strategy, such as setting targets for predischarge absolute level or percent change in level of natriuretic peptides during admissions for ADHF. Although observational and retrospective studies have shown better outcomes when levels are reduced at discharge, treating for any specific inpatient target has never been tested in any large, prospective study; thus, doing so could result in unintended harm.

So what do we know?

McQuade et al systematic review

McQuade et al57 performed a systematic review of more than 40 ADHF trials, which showed that, indeed, patients who achieved a target absolute natriuretic peptide level (BNP ≤ 250 pg/mL) or percent reduction (≥ 30%) at time of discharge had significantly improved outcomes such as reduced postdischarge all-cause mortality and rehospitalization rates. However, these were mostly prospective cohort studies that did not use any type of natriuretic peptide level-guided treatment protocol, leaving it unclear whether such a strategy could positively influence outcomes.

For this reason, both McQuade et al57 and, in an accompanying editorial, Felker et al58 called for properly designed, randomized controlled trials to investigate such a strategy. Felker noted that only 2 such phase II trials in ADHF have been completed,59,60 with unconvincing results.

PRIMA II

The Multicenter, Randomized Clinical Trial to Study the Impact of In-hospital Guidance for Acute Decompensated Heart Failure Treatment by a Predefined NT-ProBNP Target on the Reduction of Readmission and Mortality Rates (PRIMA II)60 randomized patients to natriuretic peptide level-guided treatment or standard care during admission for ADHF.

Many participants (60%) reached the predetermined target of 30% reduction in natriuretic peptide levels at the time of clinical stabilization and randomization; 405 patients were randomized. Patients in the natriuretic peptide level-guided treatment group underwent a prespecified treatment algorithm, with repeat natriuretic peptide levels measured again after the protocol.

Natriuretic peptide-guided therapy failed to show any significant benefit in any clinical outcomes, including the primary composite end point of mortality or heart failure readmissions at 180 days (36% vs 38%, HR 0.99, 95% confidence interval 0.72–1.36). Consistent with the review by McQuade et al,57 achieving the 30% reduction in natriuretic peptide at discharge, in either arm, was associated with a better prognosis, with significantly lower mortality and readmission rates at 180 days (HR 0.39 for rehospitalization or death, 95% confidence interval 0.27–0.55).

As in the observational studies, those who achieved the target natriuretic peptide level at the time of discharge had a better prognosis than those who did not, but neither study showed an improvement in clinical outcomes using a natriuretic peptide level-targeting treatment strategy.

No larger randomized controlled trial results are available for guided therapy in ADHF. However, additional insight may be gained from a subsequent trial61 that evaluated biomarker-guided titration of guideline-directed medical therapy in outpatients with chronic HFrEF.

The GUIDE-IT trial

That trial, the Guiding Evidence Based Therapy Using Biomarker Intensified Treatment in Heart Failure (GUIDE-IT)61 trial, was a large multicenter attempt to determine whether a natriuretic peptide-guided treatment strategy was more effective than standard care in the management of 894 high-risk outpatients with chronic HFrEF. Earlier, promising results had been obtained in a meta-analysis62 of more than 11 similar trials in 2,000 outpatients, with a decreased mortality rate (HR 0.62) seen in the biomarker-guided arm. However, the results had not been definitive due to being underpowered.62

Unfortunately, the results of GUIDE-IT were disappointing, with no significant difference in either the combined primary end point of mortality or hospitalization for heart failure, or the secondary end points evident at 15 months, prompting early termination for futility.61 Among other factors, the study authors postulated that this may have partly resulted from a patient population with more severe heart failure and resultant azotemia, limiting the ability to titrate neurohormonal medications to the desired dosage.

The question of whether patients who cannot achieve such biomarker targets need more intensive therapy or whether their heart failure is too severe to respond adequately echoes the question often raised in discussions of inpatient biomarker-guided therapy.58 Thus, only limited insight is gained, and it remains unclear whether a natriuretic peptide-guided treatment strategy can improve outpatient or inpatient outcomes. Until this is clarified, clinical judgment and optimization of guideline-directed management and therapy should remain the bedrock of treatment.