Ablation of atrial fibrillation: Facts for the referring physician

ABSTRACT

Radiofrequency ablation has become a safe and effective treatment for atrial fibrillation. We believe that referral to an electrophysiologist for consideration of ablation may allow for better rhythm control and outcomes by altering the natural history of atrial fibrillation progression.

KEY POINTS

- Atrial fibrillation is increasing in prevalence with the aging of the US population and is associated with worsening quality of life and increased risk of stroke, heart failure, and death.

- Atrial fibrillation results in adverse atrial remodeling and fibrosis, eventually leading to persistence of the arrhythmia and making rhythm control difficult.

- Catheter ablation has evolved to be a safe procedure with technologic advancements, especially in experienced tertiary care centers.

- The primary aim of atrial fibrillation ablation is to reduce symptoms and improve quality of life. In theory, it could also decrease the risk of stroke, heart failure, and death, but these outcomes have not been systematically evaluated in a large randomized controlled trial.

PROCEDURAL CONSIDERATIONS

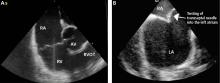

Atrial fibrillation ablation is most often performed by electrophysiologists using a minimally invasive endovascular approach. The patient can be under either moderate sedation or general anesthesia; we prefer general anesthesia for patient comfort, safety, and efficacy.

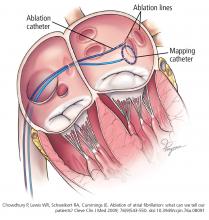

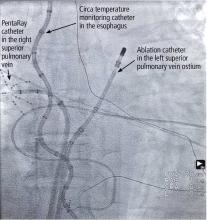

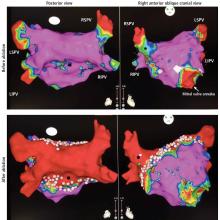

We use an electrogram-based technique to target and eliminate electrical potentials and ensure continuity of ablation sets, with additional guidance by 3-dimensional cardiac mapping systems and intracardiac echocardiography. We also use contact force-sensing catheters to ensure catheter-tissue contact during ablation and to avoid excessive contact, which may enhance the safety of the procedure.

Energy: Hot or cold

Two types of energy can be used for ablation:

Radiofrequency energy (low voltage, high frequency—30 kHz to 1.5 mHz) is delivered to the endocardial surface via a point-source catheter. The radiofrequency energy produces controlled, focal thermal ablation.

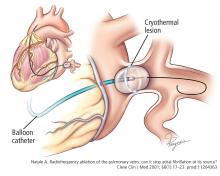

In a randomized trial,25 these ablation technologies were shown to be equivalent for preventing recurrences of atrial fibrillation. We use both in our practice. The choice depends primarily on the planned ablation set, given that balloon cryoablation can achieve antral isolation of the pulmonary veins but allows little or no substrate modification.

Improved ablation technology

Contact force-sensing catheters. Radiofrequency ablation catheters are now equipped with a pressure sensor at the tip that measures how hard the catheter is pressing on the heart wall.26,27 In our experience, this has improved the outcomes of ablation procedures, primarily in persistent atrial fibrillation.28

Complications of ablation

Although catheter ablation for atrial fibrillation is safe, it is still one of the most complex electrophysiologic procedures. Improvements in technology and techniques and accumulated experience over the past 15 years have made ablation safer, especially in tertiary care centers. But adverse outcomes are more frequent in low-volume centers.29

Minor procedural complications include pericarditis, complications at the site of vascular access, and anesthesia-related complications. While they do not affect the long-term outcome for the patient, they may increase hospital length of stay and cause temporary inconvenience.

Major complications include cardiac perforation and tamponade, periprocedural stroke, pulmonary vein stenosis, atrioesophageal fistula, phrenic nerve paralysis, major bleeding, myocardial infarction, and death. In a worldwide survey published in 2005, when atrial fibrillation ablation was still novel, the rate of major complications was 6%.30 By 2010, this had declined to 4.5%,31 and the rates of major complications may be significantly lower in more experienced centers.29 In our practice, in 2015, the rate of major complications was 1.3% (unpublished data).

Outcomes of catheter ablation

Clinical outcomes depend on many factors including the type of atrial fibrillation (paroxysmal vs nonparoxysmal), overall health of the atria (atrial size and scarring), patient age and comorbidities, and most importantly, the center’s and operator’s experience.

In randomized controlled trials comparing ablation and antiarrhythmic drug therapy, the efficacy of ablation in maintaining sinus rhythm has been in the range of 66% to 86% vs 16% to 22% for drug therapy,32,33 but these trials have been predominantly in middle-aged white men with paroxysmal atrial fibrillation. These trials also showed that catheter ablation reduced symptoms and improved quality of life. Ablation is less effective in persistent than in paroxysmal atrial fibrillation.34

In a long-term study from our group,14 660 (79.4%) of 831 patients who underwent ablation in 2005 were arrhythmia-free and not on antiarrhythmic drug therapy after a total of 1,019 ablations (an average of 1.2 ablations per patient) at a median of 55 months; 125 patients (15%, 41 with more than 1 ablation) continued to have atrial arrhythmia, controlled with drugs in 87 patients (69.6%). Only 38 patients (4.6%) continued to have drug-resistant atrial fibrillation and were treated with rate control with negative dromotropic agents.

Recent evidence

The largest randomized controlled trial of catheter ablation vs drug therapy for atrial fibrillation (Catheter Ablation Versus Antiarrhythmic Drug Therapy for Atrial Fibrillation [CABANA]) was completed recently, and the results were presented at a national meeting, although they have not yet been published in a peer-reviewed journal.35

A total of 2,204 patients with atrial fibrillation (42.4% paroxysmal, 47.3% persistent, and 10.3% long-standing persistent) were randomized to either ablation or drug therapy. Median follow-up was 4 years. The crossover rate was high—9.2% of those randomized to ablation did not undergo it, and 27.5% of those randomized to drug therapy underwent ablation.

The incidence of the primary end point (a composite of death, disabling stroke, serious bleeding, and cardiac arrest) was not significantly different between the 2 groups in the intention-to-treat analysis; however, given the high crossover rates, the as-treated and per-protocol analyses become important, and as-treated and per-protocol analyses revealed a significant benefit of ablation compared with drug therapy. The hazard ratio (HR) for the primary composite outcome was 0.67 (P = .006) on as-treated analysis and 0.73 (P = .05) on per-protocol analysis. The HR for all-cause mortality was 0.60 (P = .005) on as-treated analysis.