Ablation of atrial fibrillation: Facts for the referring physician

ABSTRACT

Radiofrequency ablation has become a safe and effective treatment for atrial fibrillation. We believe that referral to an electrophysiologist for consideration of ablation may allow for better rhythm control and outcomes by altering the natural history of atrial fibrillation progression.

KEY POINTS

- Atrial fibrillation is increasing in prevalence with the aging of the US population and is associated with worsening quality of life and increased risk of stroke, heart failure, and death.

- Atrial fibrillation results in adverse atrial remodeling and fibrosis, eventually leading to persistence of the arrhythmia and making rhythm control difficult.

- Catheter ablation has evolved to be a safe procedure with technologic advancements, especially in experienced tertiary care centers.

- The primary aim of atrial fibrillation ablation is to reduce symptoms and improve quality of life. In theory, it could also decrease the risk of stroke, heart failure, and death, but these outcomes have not been systematically evaluated in a large randomized controlled trial.

CATHETER ABLATION OF ATRIAL FIBRILLATION

The goal of ablation is to prevent atrial fibrillation by eliminating the trigger that initiates it, altering the arrhythmogenic substrate, or both.

Pulmonary vein isolation

The most common ablation strategy is to electrically isolate the pulmonary veins by creating circumferential lesions around their antra. This creates a nonconducting rim of scar tissue, electrically disconnecting the pulmonary veins from the atrium.

Ablation outside of the pulmonary veins

Because recurrence rates are high in patients with persistent atrial fibrillation who undergo pulmonary vein ablation alone, the search continues for adjunctive strategies to improve outcomes. Although these strategies have a sound rationale based on experimental data and anecdotal evidence in humans, they have not yet been convincingly shown to be helpful in large clinical studies. Nonetheless, it is possible that more extensive substrate ablation—atrial “debulking”—could improve outcomes by reducing the amount of tissue that can fibrillate.

Linear ablation. Creating lines of ablation (as in the maze procedure) isolates different segments of the left atrium. Often, these lines are created along the roof of the left atrium between the right and left upper pulmonary veins and from the mitral valve to the left inferior pulmonary vein. The benefit of linear ablation has not been proven, and gaps in such lines may introduce atrial flutter.

Triggers not in the pulmonary veins. Common sites of nonpulmonary vein triggers include the posterior wall of the left atrium, the superior vena cava, the coronary sinus, and along the ligament of Marshall. Provocative maneuvers such as isoproterenol infusion can help find those triggers, which can then be ablated. A limitation is that there is no protocol proven to reproducibly elicit triggers.

Complex fractionated atrial electrograms are areas in the atrium with highly fractionated, low voltage potentials. They may be critical sites of substrate for atrial fibrillation, and many electrophysiologists target them in patients with persistent atrial fibrillation. But despite initial enthusiasm, doing so has not resulted in better outcomes in persistent atrial fibrillation.

Rotors. Animal studies have shown that atrial fibrillation can be triggered or maintained by localized sources of organized reentrant circuits (rotors) or focal impulses. Recent studies have shown that these electrical rotors and focal sources could potentially be mapped and ablated in humans. But positive results in initial reports have not been reproduced, and this remains an area of controversy.

Our practice. We isolate the pulmonary veins with antral ablations, ablate the posterior wall, and extend the ablation toward the septum and inferior to the right pulmonary veins, with good long-term outcomes.14 The rationale behind ablating the posterior wall is that it shares embryologic origins with the pulmonary veins and may be a common source of triggers in atrial fibrillation.

We do not routinely create empiric ablation lines in the left or right atrium unless the patient has atrial flutter. Empiric ablation lines have not been convincingly shown to provide additional benefit compared with our extensive ablation approach, which involves the posterior wall. Empiric ablation of the appendage or coronary sinus is typically reserved for repeat ablation in patients with recurrent persistent atrial fibrillation.

RATIONALE FOR TREATING ATRIAL FIBRILLATION WITH ABLATION

To control symptoms

At this time, the primary aim of atrial fibrillation ablation is to reduce symptoms and improve quality of life. In theory, ablation could also decrease the risk of stroke, heart failure, and death. However, these outcomes have not been systematically evaluated in any large randomized controlled trial.

To control rhythm and improve survival

Randomized controlled trials of rhythm vs rate control of atrial fibrillation16–18 have failed to demonstrate that restoring sinus rhythm is associated with better survival. All of these trials used antiarrhythmic drugs for rhythm control. However, nonrandomized studies19,20 showed that maintaining sinus rhythm is associated with a significant reduction in mortality rates, whereas the use of antiarrhythmic drugs increased mortality risk.

This suggests that the beneficial effect of restoring sinus rhythm may be offset by adverse effects of antiarrhythmic drugs, and if rhythm control could be achieved by a method other than antiarrhythmic drug therapy, it may be superior to rate control. On the other hand, these data may be affected by residual confounding. This topic deserves further research, but maintaining sinus rhythm is typically preferred whenever possible.

Discontinuing anticoagulation is not a goal at this time

Retrospective studies have reported a low risk of stroke in patients who discontinue anticoagulation several months after undergoing atrial fibrillation ablation.21–23 However, atrial fibrillation can recur, and risk of stroke increases with age.

Therefore, guidelines24 still recommend continuing anticoagulation after ablation. Generally, we do not offer ablation with a goal of discontinuing anticoagulation. That said, stopping anticoagulation may be considered after long-term suppression of paroxysmal atrial fibrillation on a case-by-case basis in patients deemed to be at low risk. Left atrial appendage closure devices may eventually allow concomitant atrial fibrillation ablation and closure of the appendage, so that anticoagulation could then be stopped. This remains a topic of investigation.

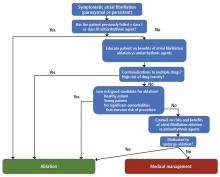

Who should be considered for ablation?

There are no absolute age or comorbidity contraindications to ablation. Everyone who has atrial fibrillation deserves, in our opinion, a referral to the electrophysiology clinic.