Evaluating suspected pulmonary hypertension: A structured approach

ABSTRACT

Pulmonary arterial hypertension (PAH) is a common consideration when patients have unexplained signs of cardiopulmonary disease. Guidelines have been issued regarding diagnosis and management of this condition. Since multiple conditions can mimic components of PAH, the clinician should think about the patient’s total clinical condition before diagnosing and categorizing it. Proper evaluation and etiologic definition are crucial to providing the appropriate therapy. This review offers a case-based guide to the evaluation of patients with suspected PAH.

KEY POINTS

- PAH has nonspecific symptoms, largely attributable to right ventricular dysfunction but seen in a host of other common cardiopulmonary ailments.

- In a patient suspected of having pulmonary hypertension, it is important to take a methodic diagnostic approach to identify underlying contributors and minimize unnecessary testing.

- Patients suspected of having PAH should be referred to a pulmonary hypertension center of excellence for evaluation and right heart catheterization.

- Once testing is complete, therapy and management should be guided both by data obtained during the initial evaluation and by factors with prognostic significance. This approach has changed PAH from a disease with a grim outlook to one in which appropriate evaluation and guidance can improve patient outcomes.

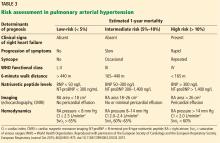

PROGNOSTIC RISK STRATIFICATION IN THE PATIENTS WITH PAH

Cardiac magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) has gained popularity as a noninvasive and reproducible alternative to echocardiography. Image fidelity and characterization of right ventricular function and right ventricular ejection fraction are all more accurate than with echocardiography, and serial MRI has proven valuable in its ability to guide patient prognosis.46

However, MRI is more expensive than echocardiography, and some patients cannot tolerate the procedure. In addition, for those who can tolerate it, MRI is not a suitable alternative to right heart catheterization, since it cannot accurately estimate pulmonary artery occlusion pressure or pulmonary arterial pressures.1 For these reasons, cardiac MRI use varies across pulmonary hypertension centers.

A goal of treatment is to reduce a patient’s risk. While no consensus has been achieved over which PAH-specific therapy to start with, evidence is robust that using more than 1 class of agent is beneficial, capitalizing on multiple therapeutic targets.17,47

In our patient, right heart catheterization revealed PAH with a mean pulmonary arterial pressure of 44 mm Hg, pulmonary artery occlusion pressure 6 mm Hg, and a cardiac index of 2.1 L/min/m2. Ancillary testing for alternative causes of PAH was unrevealing, as was vasoreactivity testing. Our patient could walk only 314 meters on her 6-minute walk test and had an initial NT-proBNP level of 750 ng/L.

Based on these and the findings during her evaluation, she would be classified as having intermediate-risk PAH with an estimated 1-year mortality risk of 5% to 10%.1 Appropriate therapy and follow-up would be guided by this determination. Specific therapy is beyond the scope of this article but we would start her on dual oral therapy with close follow-up to reassess her 1-year mortality risk. If there were no improvement over a short period of time, we would add further therapy.