Role of the incretin pathway in the pathogenesis of type 2 diabetes mellitus

ABSTRACT

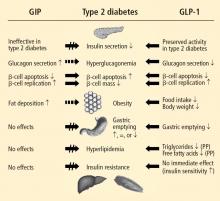

Nutrient intake stimulates the secretion of the gastrointestinal incretin hormones, glucagon-like peptide–1 (GLP-1) and glucose-dependent insulinotropic polypeptide (GIP), which exert glucose-dependent insulinotropic effects and assist pancreatic insulin and glucagon in maintaining glucose homeostasis. GLP-1 also suppresses glucose-dependent glucagon secretion, slows gastric emptying, increases satiety, and reduces food intake. An impaired incretin system, characterized by decreased responsiveness to GIP and markedly reduced GLP-1 concentration, occurs in individuals with type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM). The administration of GLP-1 improves glycemic control, but GLP-1 is rapidly degraded by the enzyme dipeptidyl peptidase–4 (DPP-4). Exenatide, a DPP-4–resistant exendin-4 GLP-1 receptor agonist, exhibits the glucoregulatory actions of GLP-1 and reduces body weight in patients with T2DM. It may possess cardiometabolic actions with the potential to improve the cardiovascular risk profile of patients with T2DM. DPP-4 inhibitors such as sitagliptin and saxagliptin increase endogenous GLP-1 concentration and demonstrate incretin-associated glucoregulatory actions in patients with T2DM. DPP-4 inhibitors are weight neutral. A growing understanding of the roles of incretin hormones in T2DM may further clarify the application of incretin-based treatment strategies.

KEY POINTS

- The incretin effect may be responsible for up to 70% of insulin secretion following oral glucose ingestion; reduction of the incretin effect contributes to T2DM pathophysiology.

- It is unknown whether incretin defects are a cause or consequence of T2DM.

- Incretin therapies effectively lower glucose with concomitant favorable effects on body weight. GLP-1 receptor agonists reduce weight, while DPP-4 inhibitors are weight neutral.

It has long been understood that the pathophysiology of type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM) is based on the triad of progressive decline in insulin-producing pancreatic beta cells, an increase in insulin resistance, and increased hepatic glucose production.1,2 It is now evident that other factors, including defective actions of the gastrointestinal (GI) incretin hormones glucagon-like peptide–1 (GLP-1) and glucose-dependent insulinotropic polypeptide (GIP), also play significant roles.2–5 The uncontrolled hyperglycemia resulting from such defects may lead to microvascular complications, including retinopathy, neuropathy, microangiopathy, and nephropathy, and macrovascular complications, such as coronary artery disease and peripheral vascular disease.

This review explores the growing understanding of the role of the incretins in normal insulin secretion, as well as in the pathogenesis of T2DM, and examines the pathophysiologic basis for the benefits and therapeutic application of incretin-based therapies in T2DM.1,2

THE GI SYSTEM AND GLUCOSE HOMEOSTASIS IN THE HEALTHY STATE

The GI system plays an integral role in glucose homeostasis.6 The observation that orally administered glucose provides a stronger insulinotropic stimulus than an intravenous glucose challenge provided insight into the regulation of plasma glucose by the GI system of healthy individuals.7 The incretin effect, as this is termed, may be responsible for 50% to 70% of the total insulin secreted following oral glucose intake.8

Two GI peptide hormones (the incretins)—GLP-1 and GIP—were found to exert major glucoregulatory actions.3,9,10 Within minutes of nutrient ingestion, GLP-1 is secreted from intestinal L cells in the distal ileum and colon, while GIP is released by intestinal K cells in the duodenum and jejunum.3 GLP-1 and GIP trigger their insulinotropic actions by binding beta-cell receptors.3 GLP-1 receptors are expressed on pancreatic glucagon-containing alpha and delta cells as well as on beta cells, whereas GIP receptors are expressed primarily on beta cells.3,8 GLP-1 receptors are also expressed in the central nervous system (CNS), peripheral nervous system, lung, heart, and GI tract, while GIP receptors are expressed in adipose tissue and the CNS.3 GLP-1 inhibits glucose-dependent glucagon secretion from alpha cells.3 In healthy individuals, fasting glucose is managed by tonic insulin/glucagon secretion, but excursions of postprandial glucose (PPG) are controlled by insulin and the incretin hormones.11

Additionally, in animal studies, GLP-1 has been shown to induce the transcriptional activation of the insulin gene and insulin biosynthesis, thus increasing beta-cell proliferation and decreasing beta-cell apoptosis.12 GLP-1 stimulates a CNS-mediated pathway of insulin secretion, slows gastric emptying, increases CNS-mediated satiety leading to reduced food intake, indirectly increases insulin sensitivity and nutrient uptake in skeletal muscle and adipose tissue, and exerts neuroprotective effects.8

Both GLP-1 and GIP are rapidly degraded by the serine protease dipeptidyl peptidase–4 (DPP-4), which is widely expressed in bound and free forms.14 A recent study in healthy adults showed that GLP-1 concentration declined even during maximal DPP-4 inhibition, suggesting that there may be pathways of GLP-1 elimination other than DPP-4 enzymatic degradation.15

INCRETINS AND THE PATHOGENESIS OF T2DM

Studies have shown that incretin pathways play a role in the progression of T2DM.3,16 The significant reduction in the incretin effect seen in patients with T2DM has been attributed to several factors, including impaired secretion of GLP-1, accelerated metabolism of GLP-1 and GIP, and defective responsiveness to both hormones.16 Many patients with T2DM also have accelerated gastric emptying that may contribute to deterioration of their glycemic control.17

While GIP concentration is normal or modestly increased in patients with T2DM,16,18 the insulinotropic actions of GIP are significantly diminished.19 Thus, patients with T2DM have an impaired responsiveness to GIP with a possible link to GIP-receptor downregulation or desensitization.20

Are secretory defects a cause or result of T2DM?

In contrast to GIP, the secretion of GLP-1 has been shown to be deficient in patients with T2DM.18 As with GIP, it is unknown to what degree this defect is a cause or consequence of T2DM. In a study of identical twins, defective GLP-1 secretion was observed only in the one sibling with T2DM, suggesting that GLP-1 secretory deficits may be secondary to the development of T2DM.21 Despite the diminished secretion of GLP-1 in patients with T2DM, the insulinotropic actions of GLP-1 are preserved.19 It has also been shown that the effects of GLP-1 on gastric emptying and glucagon secretion are maintained in patients with T2DM.19,22,23

Whether this incretin dysregulation is responsible for or is the end result of hyperglycemia remains a subject of continued investigation. A recent study confirmed that the incretin effect is reduced in patients with T2DM, but advanced the concept that it may be a consequence of the diabetic state.16,24 Notably, impaired actions of GLP-1 and GIP and diminished concentrations of GLP-1 may be partially restored by improved glycemic control.24

Recent preclinical and clinical studies continue to clarify the roles of incretin hormones in T2DM. The findings from a study of obese diabetic mice suggest that the effect of GLP-1 therapy on the long-term remission of diabetes may be caused by improvements in beta-cell function and insulin sensitivity, as well as by a reduction in gluconeogenesis in the liver.25

Incretin effect and glucose tolerance, body mass index

Another study was conducted to evaluate quantitatively the separate impacts of obesity and hyperglycemia on the incretin effect in patients with T2DM, patients with impaired glucose tolerance, and patients with normal glucose tolerance.26 There was a significant (P ≤ .05) reduction in the incretin effect in terms of total insulin secretion, beta-cell glucose sensitivity, and the GLP-1 response to oral glucose in patients with T2DM compared with individuals whose glucose tolerance was normal or impaired. Each manifestation of the incretin effect was inversely related to both glucose tolerance and body mass index in an independent, additive manner (P ≤ .05); thus, glucose tolerance and obesity attenuate the incretin effect on beta-cell function and GLP-1 response independently of each other.

Exogenous GLP-1 has been shown to restore the regulation of blood glucose to near-normal concentrations in patients with T2DM.27 Several studies of patients with T2DM have shown that synthetic GLP-1 administration induces insulin secretion,19,27 slows gastric emptying (which is accelerated in patients with T2DM), and decreases inappropriately elevated glucagon secretion.19,23,28 Acute GLP-1 infusion studies showed that GLP-1 improved fasting plasma glucose (FPG) and PPG concentrations23,27; long-term studies showed that this hormone exerts euglycemic effects, leading to improvements in glycosylated hemoglobin (HbA1c), and induces weight loss.29