The experts debate: Perioperative beta-blockade for noncardiac surgery—proven safe or not?

ABSTRACT

Guidelines on perioperative management of patients undergoing noncardiac surgery recommend the use of prophylactic perioperative beta-blockers in high-risk patients who are not already taking them, and their continuance in patients on chronic beta-blockade prior to surgery. These recommendations were challenged recently by results of the Perioperative Ischemic Evaluation (POISE), a large randomized trial of extended-release metoprolol succinate started immediately before noncardiac surgery in patients at high risk for atherosclerotic disease. While metoprolol significantly reduced myocardial infarctions relative to placebo in POISE, it also was associated with significant excesses of both stroke and mortality. The merits and limitations of POISE and its applicability in light of other trials of perioperative beta-blockade are debated here by two experts in the field—Dr. Don Poldermans and Dr. P.J. Devereaux (co-principal investigator of POISE).

Safety of perioperative beta-blocker use has not been adequately demonstrated

By P.J. Devereaux, MD, PhD

I contend that perioperative beta-blockade is a practice not grounded in evidence-based medicine, and its overall safety has increasingly come into question as more data from large, high-quality trials have emerged. I will begin with a historical overview of perioperative beta-blocker use, review the results of the POISE trial (for which I was the co-principal investigator), explore the major questions raised by this trial, and conclude with some take-away messages.

THE HISTORY OF PERIOPERATIVE BETA-BLOCKADE

In the 1970s, physicians were encouraged to hold beta-blockers prior to surgery out of concern that these medications may inhibit the required cardiovascular response when patients developed hypotension, and could thereby lead to serious adverse consequences.

In the 1980s, new research associated tachycardia with perioperative cardiovascular events, leading to proposals to implement perioperative beta-blocker use.

In the 1990s, two randomized trials with a total sample size of 312 patients1,3 suggested that perioperative beta-blockers had a large treatment effect in preventing major cardiovascular events and death. These small trials had several methodological limitations:

- One trial3 was unblinded in a setting in which the vast majority of MIs are clinically silent.

- One trial3 was stopped early—after randomizing only 112 patients—for unexpected large treatment effects.

- One of the studies1 failed to follow intention-to-treat principle.

Nevertheless, guidelines developed at the time by the American College of Cardiology and the American Heart Association (ACC/AHA) recommended the use of perioperative beta-blockers on the basis of the physiological rationale and these two small clinical trials. That recommendation was retained in the latest (2007) update of the ACC/AHA perioperative guidelines.20

In 2006, two clinical trials with a total sample size of 1,417 were completed,4,15 surpassing the total size of previous trials by more than fourfold. These two more recent trials did not suffer from the methodological limitations of earlier trials. These trials showed no benefit of perioperative beta-blocker use; in fact, there was a trend toward worse outcomes in the beta-blocker recipients.4,15 Despite these new data, guidelines committees continued to recommend perioperative beta-blockade.20

THE POISE TRIAL

Study design

This was the context into which the POISE results were released in 2008. POISE was a randomized, controlled, blinded trial of patients 45 years or older scheduled for noncardiac surgery who had, or were at high risk of, atherosclerotic disease.14 The intervention consisted of metoprolol succinate (metoprolol controlled release [CR]) or placebo started 2 to 4 hours preoperatively (if heart rate was ≥ 50 beats per minute and systolic blood pressure [SBP] was ≥ 100 mm Hg) and continued for 30 days. The target dosage of metoprolol was 200 mg once daily. No patients received the recommended maximum dosage of 400 mg over 24 hours. The main outcome measure was a 30-day composite of cardiovascular death, nonfatal MI, or nonfatal cardiac arrest.

We randomized 9,298 patients in a 1:1 ratio to metoprolol or placebo. We encountered data fraud at a number of centers that prompted exclusion of data from 474 patients allocated to metoprolol and 473 allocated to placebo. Therefore, the total number of patients available for the intention-to-treat analysis was 8,351, from 190 centers in 23 countries.

Results

The risk of the primary composite outcome was reduced by 16% (relative reduction) in recipients of metoprolol CR compared with placebo recipients (P = .0399). Significantly fewer nonfatal MIs occurred in the metoprolol CR group than in the placebo group (152 [3.6%] vs 215 [5.1%]; P = .0008), leaving little doubt that perioperative beta-blockade prevents MI.

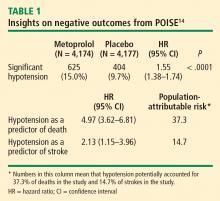

In contrast, total mortality was increased in the beta-blocker group, with 129 deaths among those assigned to metoprolol CR and 97 among those assigned to placebo (P = .0317), and the incidence of stroke was also significantly greater in the metoprolol CR group (1.0% vs. 0.5%; P = .0053).

Consistency with findings from other trials

The POISE data are consistent with those from a 2008 meta-analysis of high-quality randomized controlled trials in noncardiac surgery patients, which showed a significantly greater risk of death among patients assigned to a beta-blocker than among controls who were not (160 deaths [2.8%] vs 127 deaths [2.3%]; odds ratio [OR] = 1.27 [95% CI, 1.01–1.61]).21 This meta-analysis also found a significantly greater risk of nonfatal stroke in beta-blocker recipients compared with controls (38 [0.7%] vs 17 [0.3%]; OR = 2.16 [95% CI, 1.27–3.68]).

I also contend that the DECREASE IV trial supports the POISE findings in that although few strokes were encountered in DECREASE IV, the trend was in the direction of harm in the beta-blocker group, which had 4 strokes among 533 patients versus 3 strokes among 533 patients not receiving the beta-blocker.17

Predictive role of hypotension

The link between hypotension and death in POISE is consistent with findings from the largest beta-blocker trial undertaken, COMMIT (Clopidogrel and Metoprolol in Myocardial Infarction Trial), in which 45,852 patients with acute MI were randomized to metoprolol or placebo.22 In COMMIT, metoprolol had no effect on 30-day all-cause mortality but significantly reduced the risk of arrhythmic death, a benefit that was countered by a significantly increased risk of death from shock with a beta-blocker in acute MI. Clinically significant hypotension is much more common in the perioperative setting than in acute MI, which may explain the excess number of deaths observed with metoprolol in POISE as opposed to metoprolol’s neutral effect on mortality in COMMIT.