The experts debate: Perioperative beta-blockade for noncardiac surgery—proven safe or not?

ABSTRACT

Guidelines on perioperative management of patients undergoing noncardiac surgery recommend the use of prophylactic perioperative beta-blockers in high-risk patients who are not already taking them, and their continuance in patients on chronic beta-blockade prior to surgery. These recommendations were challenged recently by results of the Perioperative Ischemic Evaluation (POISE), a large randomized trial of extended-release metoprolol succinate started immediately before noncardiac surgery in patients at high risk for atherosclerotic disease. While metoprolol significantly reduced myocardial infarctions relative to placebo in POISE, it also was associated with significant excesses of both stroke and mortality. The merits and limitations of POISE and its applicability in light of other trials of perioperative beta-blockade are debated here by two experts in the field—Dr. Don Poldermans and Dr. P.J. Devereaux (co-principal investigator of POISE).

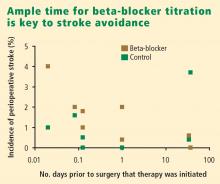

What about timing of beta-blocker initiation?

The POISE findings may also be explained in part by the timing of beta-blocker initiation. Whereas bisoprolol was carefully titrated for 30 days before surgery in DECREASE, metoprolol was initiated just before surgery in POISE, and the maximum recommended dose may have been prescribed during the first 24 hours, although subsequent dosing was 200 mg daily, which is 50% of the maximum daily therapeutic dose. This extremely narrow time window for titration may be important, since the beneficial effects of beta-blockade on coronary plaque stability are likely to take weeks to develop.

Reassurance from a large case-control study

My colleagues and I conducted a case-control study from among more than 75,000 patients who underwent noncardiac, nonvascular surgery at our institution, Erasmus Medical Center, from 1991 to 2001.18 The cases were the 989 patients who died in the hospital postoperatively; the controls were 1,879 survivors matched with the cases for age, sex, the year the surgery was performed, and the type of surgery. The incidence of perioperative stroke was 0.5%, which is comparable to the rate found in the literature. Risk factors predictive of stroke were the presence of diabetes, cerebrovascular disease, peripheral arterial disease, atrial fibrillation, coronary artery disease, and hypertension. Notably, no relationship was found between chronic beta-blocker use and stroke.

WHAT ABOUT PATIENTS AT INTERMEDIATE RISK?

Because the effect of perioperative beta-blockade has traditionally been ill defined in surgical patients at intermediate risk of cardiovascular events, the DECREASE study group recently completed a study (DECREASE IV) to assess perioperative bisoprolol in terms of cardiac morbidity and mortality in intermediate-risk patients undergoing elective noncardiovascular surgery.17 Enrollees had a score of 1 to 2 on the Revised Cardiac Risk Index of Lee et al,19 which corresponds to an estimated risk of between 1% and 6% for a perioperative cardiovascular event.17

DECREASE IV also aimed to assess the effect of perioperative fluvastatin, so a 2 x 2 factorial design was used in which the study’s 1,066 patients were randomized to receive bisoprolol, fluvastatin, combination treatment, or combination placebo control. Bisoprolol was initiated up to 30 days prior to surgery, and the 2.5-mg daily starting dosage was titrated according to the patient’s heart rate to achieve a target rate of 50 to 70 beats per minute. Fluvastatin was also started up to 30 days prior to surgery. Patients who received bisoprolol (with or without fluvastatin) had a significant reduction in the 30-day incidence of cardiac death and nonfatal MI compared with those who did not receive bisoprolol (2.1% vs 6.0%; HR = 0.34 [95% CI, 0.17–0.67]; P = .002). Fluvastatin was associated with a favorable trend on this end point, but statistical significance was not achieved (P = .17).17

There was no difference among treatment groups in the incidence of stroke (4 strokes in the 533 patients who received bisoprolol vs 3 strokes in the 533 patients who did not),17 which further suggests that the increased stroke rate seen with beta-blockade in POISE may have been due to dosage, timing of initiation, or both.

CONCLUSIONS

Dose-related hypotension may explain POISE findings

Our understanding of postoperative stroke is incomplete, but it appears that dosing of a beta-blocker can be a contributor, especially with respect to the potential side effect of hypotension during surgery. Keep in mind that the average age of patients in POISE was approximately 70 years and that patients were naïve to beta-blockers. Some may have had asymptomatic left ventricular dysfunction, and we know that starting a beta-blocker at a high dose in such patients may lead to hypotension. At my institution we routinely perform echocardiographic screening of all patients scheduled for surgery, and we have found that more than half of the patients with heart failure have it uncovered only through this screening.

It is not the medicine alone that can cause perioperative hypotension; other factors may induce hypotension, requiring beta-blocker titration and careful monitoring of hemodynamics during surgery.

Advice: Start early and titrate dose; continue chronic beta-blockade

My advice is as follows:

- If a patient is on chronic beta-blocker therapy, do not stop it perioperatively. We have seen devastating outcomes in the Netherlands when patients had their beta-blockers stopped immediately before surgery. Consider adjusting the dose, but do not stop it entirely. If a beta-blocker is on board and the patient develops hypotension or bradycardia during surgery, treat the symptoms and check for sepsis.

- In a patient not on a beta-blocker, consider adding one if the patient is at intermediate or high risk of a cardiac event, but start at a low dosage (ie, 2.5 mg/day for bisoprolol and 25 mg/day for metoprolol). Treatment ideally should be started 30 days preoperatively; in the Netherlands, we have the chance to start well in advance of surgery so we can titrate the dose according to hemodynamics.

- If a beta-blocker is not started because of insufficient time for titration, do not add one to treat tachycardia that develops during surgery, since tachycardia may represent a response to normal defense mechanisms.