Perioperative management of diabetes: Translating evidence into practice

ABSTRACT

Glycemic control before, during, and after surgery reduces the risk of infectious complications; in critically ill surgical patients, intensive glycemic control may reduce mortality as well. The preoperative assessment is important in determining risk status and determining optimal management to avoid clinically significant hyper- or hypoglycemia. While patients with type 1 diabetes should receive insulin replacement at all times, regardless of nutritional status, those with type 2 diabetes may need to stop oral medications prior to surgery and might require insulin therapy to maintain blood glucose control. The glycemic target in the perioperative period needs to be clearly communicated so that proper insulin replacement, consisting of basal (long-acting), prandial (rapid-acting), and supplemental (rapid-acting) insulin can be implemented for optimal glycemic control. The postoperative transition to subcutaneous insulin, if needed, can begin 12 to 24 hours before discontinuing intravenous insulin, by reinitiation of basal insulin replacement. Basal/bolus insulin regimens are safer and more effective in hospitalized patients than supplemental-scale regular insulin.

KEY POINTS

- Surgery and anesthesia can induce hormonal and inflammatory stressors that increase the risk of complications in patients with diabetes.

- Elevated blood glucose levels are associated with worse outcomes in surgical patients, even among those not diagnosed with diabetes.

- The perioperative glycemic target in critically ill patients is 140 to 180 mg/dL. Evidence for a target in patients who are not critically ill is less robust, though fasting levels less than 140 mg/dL and random levels less than 180 mg/dL are appropriate.

- Postoperative nutrition-related insulin needs vary by nutrition type (parenteral or enteral), but ideally all regimens should incorporate a basal/bolus approach to insulin replacement.

POSTOPERATIVE GLYCEMIC MANAGEMENT

Start subcutaneous transition before stopping IV drip

Transitioning from IV to subcutaneous insulin is often complicated. Nonoral nutrition options (ie, parenteral nutrition or enteral supplementation) must be considered. As noted, insulin must be replaced according to physiologic needs, which requires that a long-acting basal insulin be used regardless of oral intake status, a rapid-acting insulin be given to cover prandial or nutritional needs, and supplemental rapid-acting insulin be used to correct hyperglycemia.

In the transition from IV insulin, basal insulin replacement can begin at any time. I recommend starting the transition from IV to subcutaneous insulin about 12 to 24 hours before discontinuing the insulin drip. In type 1 diabetes, this transition ensures basal insulin coverage and minimizes the risk of developing ketones and ketoacidosis. In type 2 diabetes, it can ensure a more stable transition and better glycemic control.

Determining the basal insulin dose

Switching to subcutaneous supplemental insulin

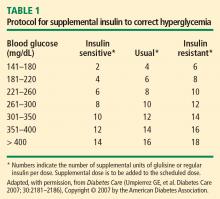

Instructions must be given for switching to subcutaneous supplemental doses of insulin. Glycemic targets, generally from less than 130 to 150 mg/dL, must be established, as must the frequency of fingerstick testing:

- If the patient is being fed enterally or parenterally, fingerstick testing is recommended every 4 to 6 hours if a rapid-acting insulin analog is used and every 6 hours if regular insulin is used.

- If the patient is eating, fingerstick testing should be performed before meals and at bedtime.

Covering nutritional requirements

Nutrition-related insulin needs depend on the type of caloric intake prescribed:

In patients receiving total parenteral nutrition (TPN), start 1 U of regular insulin (placed in the bag) for every 10 to 15 g of dextrose in the TPN mixture.

In patients receiving enteral nutrition, use regular insulin every 6 hours or a rapid-acting insulin analog every 4 hours. Start 1 U of insulin subcutaneously for every 10 to 15 g of delivered carbohydrates. For example, if a patient is receiving 10 g of carbohydrates per hour, a rapid-acting analog given at a dose of 4 U every 4 hours (1 U per 10 g of carbohydrates) should adequately cover enteral feedings. For any bolus feedings, give the injection as a full bolus 15 to 20 minutes in advance, based on the carbohydrate content of the feeding.

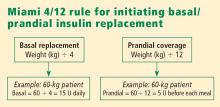

In patients who are eating, use regular insulin or a rapid-acting insulin analog before meals. Again, start 1 U of insulin subcutaneously for every 10 to 15 g of carbohydrates, or use the prandial portion of the Miami 4/12 rule (Figure 2). For example, in a 60-kg patient one would start with 5 U (60 ÷ 12) of a rapid-acting insulin before each meal.

Basal/bolus replacement outperforms supplemental-scale regular insulin

Use of a basal/bolus insulin regimen appears to be more beneficial than supplemental-scale regular insulin in hospitalized patients with type 2 diabetes, according to a recent randomized trial comparing the two approaches in 130 such patients with blood glucose levels greater than 140 mg/dL.17 In the group randomized to basal/bolus insulin, the starting total daily dose was 0.4 to 0.5 U/kg/day, with half the dose given as basal insulin (insulin glargine) once daily and half given as a rapid-acting insulin analog (glulisine) in fixed doses before every meal. A rapid-acting analog was used for supplemental insulin in the basal/bolus regimen. By study’s end, patients in the basal/bolus group were receiving a higher total daily insulin dose than those in the supplemental-scale group (mean of 42 U/day vs 13 U/day).

Mean daily blood glucose levels were 27 mg/dL lower, on average, in patients who received basal/bolus therapy compared with the supplemental-scale group, yet there was no difference between groups in the risk of hypoglycemia. More patients randomized to basal/bolus therapy achieved the glycemic goal of less than 140 mg/dL (66% vs 38%). Fourteen percent of patients assigned to supplemental-scale insulin had values persistently greater than 240 mg/dL and had to be switched to the basal/bolus regimen.17

SUMMARY

Perioperative glycemic control can reduce morbidity, particularly the incidence of infectious complications, in surgical patients, even in those without diagnosed diabetes. Optimal management of glycemia in the perioperative period involves applying principles of physiologic insulin replacement. Postoperatively, the transition from IV to subcutaneous insulin can be achieved through the use of basal insulin for coverage of fasting insulin needs, regardless of the patient’s feeding status, and the use of rapid-acting insulin to cover hyperglycemia and nutritional needs. Management of hospitalized patients exclusively with supplemental-scale regular insulin should be abandoned.