Cardiac risk stratification for noncardiac surgery

ABSTRACT

The American College of Cardiology and American Heart Association updated their joint guidelines on perioperative cardiovascular evaluation and care for noncardiac surgery in 2007. The guidelines recommend preoperative cardiac testing only when the results may influence patient management. They specify four high-risk conditions for which evaluation and preoperative treatment are needed: unstable coronary syndromes, decompensated heart failure, significant cardiac arrhythmias, and severe valvular disease. Patient-specific factors and the risk of the surgery itself are considerations in the need for an evaluation and the treatment strategy before noncardiac surgery. In most instances, coronary revascularization before noncardiac surgery has not been shown to reduce morbidity and mortality, except in patients with left main disease. The timing of surgery following percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) depends on whether a stent was used, the type of stent, and the antiplatelet regimen.

KEY POINTS

- In addition to patient-specific factors, preoperative cardiac assessment should account for the risk of cardiac morbidity related to the procedure itself. Vascular surgery confers the highest risk, with reported rates of cardiac morbidity often greater than 5%.

- Continuation of chronic beta-blocker therapy is prudent during the perioperative period.

- Coronary revascularization prior to noncardiac surgery is generally indicated only in unstable patients and in patients with left main disease.

- Nonurgent noncardiac surgery should be delayed for at least 30 days after PCI using a bare-metal stent and for at least 365 days after PCI using a drug-eluting stent.

- Discontinuing antiplatelet therapy in patients with coronary stents may induce a hypercoagulable state within approximately 7 to 10 days.

HEART RATE CONTROL

Chronic beta-blockade can obviate need for cardiac testing

The DECREASE (Dutch Echocardiographic Cardiac Risk Evaluation Applying Strees Echo) II trial assessed the value of cardiac testing before major vascular surgery in intermediate-risk patients (ie, with one or two cardiac risk factors) receiving chronic beta-blocker therapy begun 7 to 30 days prior to surgery.7 Among the study’s 770 intermediate-risk patients, the primary outcome—cardiac death or MI at 30 days—was no different between those randomized to receive stress testing or no stress testing. The investigators concluded that cardiac testing can safely be omitted in intermediate-risk patients if beta-blockers are used with the aim of tight heart rate control.

Continue ongoing beta-blocker therapy, start in select high-risk patients

The ACC/AHA 2007 perioperative guidelines recommend continuing beta-blocker therapy in patients who are already receiving these agents (Class I, Level C). For patients not already taking beta-blockers, their initiation is recommended in those undergoing vascular surgery who have ischemia on preoperative testing (Class I, Level B). The guidelines designate beta-blockers as “probably” recommended (Class IIa, Level B) for several other patient subgroups with high cardiac risk, mainly in the setting of vascular surgery.1

Notably, the guidelines were written before publication of the Perioperative Ischemic Evaluation (POISE),8 which questioned the risk/benefit profile of perioperative beta-blockade in patients with or at high risk of atherosclerotic disease (see the Poldermans–Devereaux debate on page S84 of this supplement), and therefore may require revision (an update is scheduled for release in November 2009).

LIMITED ROLE FOR CORONARY REVASCULARIZATION

Until recently, no randomized trials had assessed the benefit of prophylactic coronary revascularization to reduce the perioperative risk of noncardiac surgery. The first large such trial was the Coronary Artery Revascularization Prophylaxis (CARP) study, which randomized 510 patients scheduled for major elective vascular surgery to undergo or not undergo coronary artery revascularization before the procedure.9 The study found that revascularization failed to affect any outcome measure, including mortality or the development of MI, out to 6 years of follow-up. Notably, the CARP population consisted mostly of patients with single-, double-, or mild triple-vessel coronary artery disease, so the study was limited in that it did not include patients with strong indications for coronary artery bypass graft surgery (CABG).7

A reanalysis of the CARP results by the type of revascularization procedure—CABG or percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI)—revealed that patients undergoing CABG had lower rates of death, MI, and additional revascularization procedures compared with those undergoing PCI, despite the presumably more extensive disease of the CABG recipients.10

Benefit apparently limited to left main disease

Further analysis of patients in the CARP trial who underwent coronary angiography found that one subgroup—patients with left main disease—did experience an improvement in survival with preoperative coronary revascularization.11

In a subsequent randomized pilot study, Poldermans et al found no advantage to preoperative coronary revascularization among patients with extensive ischemia who underwent major vascular surgery.12 While this study was not adequately sized to definitively address the value of preoperative revascularization in these high-risk patients, its results are consistent with those of the CARP trial.

In a retrospective cohort study of patients who underwent noncardiac surgery, Posner and colleagues found that rates of adverse cardiac outcomes among patients who had recent PCI (≤ 90 days before surgery) were similar to rates among matched controls with nonrevascularized coronary disease.13 Patients who had had remote PCI (> 90 days before surgery) had a lower risk of poor outcomes than did matched controls with nonrevascularized disease, but had a higher risk than did controls without coronary disease.13

PATIENTS WITH CORONARY STENTS: STENT TYPE AND TIME SINCE PLACEMENT ARE KEY

The lack of benefit from prophylactic PCI prior to noncardiac surgery also applies to PCI procedures that involve coronary stent placement. For instance, a propensity-score analysis found no benefit from prophylactic PCI (using stents in the vast majority of cases) in patients with coronary artery disease in terms of adverse coronary events or death following aortic surgery.14

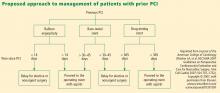

In patients who have undergone prior PCI, noncardiac surgery poses special challenges, especially in relation to stents. Restenosis is a particular concern with the use of bare-metal stents, and development of stent thrombosis is a particular risk with the use of drug-eluting stents.15 The use of drug-eluting stents requires intensive antiplatelet therapy for at least 1 year following stent implantation to prevent stent thrombosis.16

Time interval to surgery after bare-metal stent placement

The effect of prior PCI with bare-metal stents on outcomes following noncardiac surgery was examined in a recent large retrospective study by Nuttall et al.17 The incidence of major cardiac events was found to be lowest when noncardiac surgery was performed more than 90 days after PCI with bare-metal stents. Using patients who had a greater than 90-day interval before surgery as the reference group, propensity analysis showed that performing surgery within 30 days of PCI was associated with an odds ratio of 3.6 for major cardiac events. The odds ratio was reduced to 1.6 when surgery was performed 31 to 90 days after PCI. These findings suggest that 30 days may be an ideal minimum time interval, from a risk/benefit standpoint, between PCI with bare-metal stents and noncardiac surgery.

Time interval to surgery after drug-eluting stent placement

A recent retrospective study by Rabbitts et al examined patients who had noncardiac surgery after prior PCI with drug-eluting stents, focusing on the relationship between the timing of the procedures and major cardiac events during hospitalization for the surgery.18 Although the frequency of major cardiac events was not statistically significantly associated with the time between stent placement and surgery, the frequency was lowest—3.3%—when surgery followed drug-eluting stent placement by more than 365 days (versus rates of 5.7% to 6.4% for various intervals of less than 365 days).

ACC/AHA recommendations

Timing of antiplatelet interruption

Results from a prospectively maintained Dutch registry19 are consistent with the findings reviewed above: patients who underwent noncardiac surgery less than 30 days after bare-metal stent implantation or less than 6 months after drug-eluting stent implantation (early surgery group) had a significantly elevated rate of major cardiac events compared with patients in whom the interval between stenting and noncardiac surgery was longer (late surgery group). Notably, this report also found that the rate of major cardiac events within the early surgery group was significantly higher in patients whose antiplatelet therapy was discontinued during the preoperative period than in those whose antiplatelet therapy was not stopped.19

A hypercoagulable state develops within 7 to 10 days after interruption of antiplatelet therapy, at which time the patient is vulnerable to thrombosis. In general, surgery should not proceed during this time without antiplatelet coverage.

From my perspective, giving ketorolac or aspirin the morning of surgery may be beneficial for patients whose antiplatelet therapy has been stopped 7 to 10 days previously, although no data from randomized trials exist to support this practice. Theoretically, it is reasonable to stop antiplatelet therapy 4 to 5 days before surgery in patients with an increased risk of bleeding without exposing them to the hypercoagulability that would set in if therapy were stopped earlier.