The prevalence and natural history of hepatitis B in the 21st century

ABSTRACT

The prevalence of chronic hepatitis B virus (HBV) infection varies by geographic region. Most of North America is a low-prevalence (< 2%) area. Certain high-prevalence pockets exist, especially areas with a high proportion of Asian immigrants and Alaskan and northern Canadian native populations, where rates of chronic HBV are as high as 5% to 15%. In most low-prevalence areas, HBV infection is acquired mainly during adolescence and midadulthood, whereas perinatal transmission is the main route in high-prevalence (≥ 8%) areas. Up to 40% of patients with chronic HBV infection develop liver complications. Age at acquisition affects the likelihood of chronicity and the development of liver complications. The risk of each is greatest with perinatal transmission; the disease is usually self-limiting when exposure to HBV occurs during adolescence or young adulthood. Viral load predicts progression to cirrhosis and hepatocellular carcinoma; therefore, reducing viral load is the major goal of treatment.

KEY POINTS

- The prevalence of chronic HBV infection in the United States is expected to increase as Asian immigrants constitute a larger proportion of the US population.

- The chance of chronic infection is 90% or greater with perinatal transmission; conversely, the risk of chronic disease is less than 10% with adult-acquired infection.

- In addition to viral load, predictors of disease progression include age at onset, male sex, and comorbidities.

NATURAL HISTORY OF CHRONIC HBV INFECTION

Chronic HBV usually causes microinflammatory changes that evoke a fibrotic response in the liver, and many infected individuals will eventually develop cirrhosis and are at risk for the development of HCC. Inactive HBsAg carriers often bypass the development of cirrhosis but remain at risk for HCC if their viral load is very high. This is particularly true when infection is acquired in infancy.

The age at acquisition of HBV has a large impact on the likelihood of the disease becoming chronic. The chance of chronic infection is 90% or greater among neonates who become infected with HBV through perinatal transmission. Exposure during adolescence or young adulthood is associated with a 95% or greater likelihood that the disease will be self-limiting.

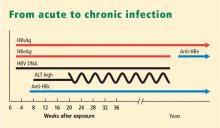

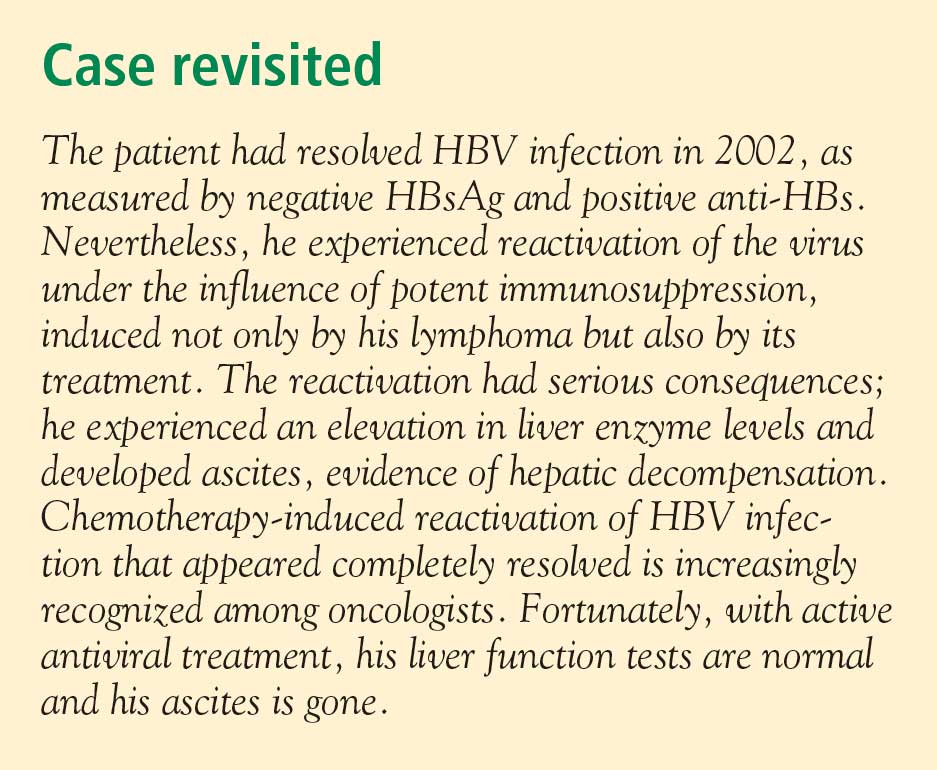

The typical North American patient with HBV acquires the infection as an adolescent or young adult and is not at risk of HCC unless cirrhosis develops. In most patients who acquire the disease in adolescence or adulthood, the infection resolves after weeks or a few months and they are not at risk of either cirrhosis or HCC. However, an individual such as the one described in the accompanying case, who becomes immunocompromised, is at risk of reactivation of HBV infection (see “Case revisited”).

HBV MODES OF TRANSMISSION

In low-prevalence areas, such as most of North America, most cases of HBV infection are acquired during adolescence to midadulthood, a period during which behaviors that increase the risk of HBV infection (ie, intravenous drug abuse or unprotected sexual activity) are most likely.9,10 Sex workers and homosexuals are at particular risk of sexual transmission of HBV. Intravenous drug abusers and health workers are at risk of parenteral transmission.

In high-prevalence areas, HBV is mostly transmitted during the perinatal period from mother to infant, conferring a high likelihood of chronicity.9,10 Mothers who are HBsAg positive, particularly those who are also HBeAg positive, are much more likely than others to transmit HBV to their offspring.

FACTORS THAT INFLUENCE THE COURSE OF HBV INFECTION

Viral load has emerged as the most significant factor implicated in the development of cirrhosis or HCC. Iloeje et al11 found that viral load predicted progression to cirrhosis among a cohort of nearly 4,000 Taiwanese. Other factors that can influence the course of HBV infection include age at onset, male sex, and comorbidities (ie, alcohol use, human immunodeficiency virus infection, hepatitis C virus infection). Core promoter and precore mutants may affect the likelihood of developing HCC. A genetic signature that predisposes liver cells to proliferate, termed field effects, may also lead to the development of HCC. The influence of smoking and diabetes on the development of HCC in HBV-infected individuals is not well documented.

Reduction or elimination of measurable virus is the current holy grail of treatment; available antiviral therapies are potent tools that lower viral load with the hope of reducing the likelihood of either cirrhosis or HCC.

HBV genotypes may be implicated in the progression of liver disease or the risk of development of HCC. HBV genotypes differ by region and may correlate with ethnicity and disease progression. In a study of 694 US patients with chronic HBV, Chu et al12 found that genotypes A and C were associated with a higher prevalence of HBsAg positivity than other genotypes. Genotypes B and C were the most common among Asian American patients, while genotype A was the most common among Caucasian and African American patients. The authors suggested that HBV genotypes may explain the heterogeneity in the manifestation of the disease.