Treatment Options for Stable Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease: Current Recommendations and Unmet Needs

Pharmacologic treatment recommendations

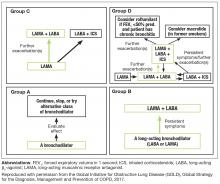

Recent updates of the GOLD recommendations acknowledge the discordance between lung function and symptoms in patients with COPD. The 2017 recommendations use symptoms and exacerbation risk to define the ABCD categories that guide therapy selection. However, the GOLD authors still acknowledge the importance of spirometry in diagnosis, prognostic evaluation, and treatment with nonpharmacologic interventions in patients with COPD.3

- GOLD A patients: initial treatment with a short- or long-acting bronchodilator

- GOLD B patients: initial treatment with a single long-acting muscarinic receptor antagonist (LAMA) or long-acting β2-agonist (LABA). If symptoms (such as dyspnea) are severe at initiation of therapy, or persistent with use of 1 long-acting bronchodilator, LAMA/LABA combination is recommended

- GOLD C patients: initial treatment with a LAMA (LAMA is the preferred treatment due to superior exacerbation prevention versus LABA), with preferred escalation to LAMA/LABA if further exacerbations occur. Escalation to ICS/LABA combination may be considered (although is not preferred due to possible risk of pneumonia21)

- GOLD D patients: initial treatment with LAMA/LABA; initial treatment with ICS/LABA may be preferred in patients with a history and/or findings suggestive of asthma–COPD overlap or high blood eosinophil counts (but consider the risk of pneumonia). Escalation to ICS/LAMA/LABA triple therapy may be considered if symptoms persist or further exacerbations occur.

GOLD grades provide a valuable guide for initiating therapy and continuing assessment and care. Initial therapy may provide sufficient disease control in some patients, but disease progression and persistent symptoms despite therapy often require treatment escalation. Assessing and escalating therapy should be based on changes in functional status and symptom burden, which can be identified by asking appropriate questions, or performing tests to evaluate functional capacity, such as the 6-minute walk test.3 The modified Medical Research Council (mMRC) dyspnea scale is also a good example of a quick tool for baseline assessment of the patient’s functional status. This assessment must be coupled with appropriate follow-up. During follow-up visits, it is important to ask patients about their typical daily activities, and assess how these compare to what has been reported previously. Follow-up visits can also be an opportunity to check that a patient is using their inhaler device correctly.

Regular assessment of patients’ health status is important for optimal disease management.22 The COPD Assessment Test (CAT) is a short, simple, COPD patient-completed questionnaire, designed to inform the clinician about the severity and impact of a patient’s disease. Changes in patients’ functional abilities and symptoms over time can be monitored with regular use of the CAT at COPD visits.23 Although the CAT test facilitates prediction of COPD exacerbations,24 it is not intended to identify comorbidities; for example, the mental health comorbidities of COPD (including anxiety, sleep disturbances, and depression) are often unreported by patients and so can be difficult for clinicians to detect.25 Awareness of possible comorbid conditions, and appropriate screening for conditions such as depression (PHQ-2), anxiety (GAD-7), or osteoporosis (BMD) is recommended.26 Further details of PHQ-2 and GAD-7 are provided in the second article (Anxiety and Depression in Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease: Recognition and Management) of this supplement.

Physicians need to make decisions about whether (and how) treatment should be escalated using parameters in addition to frequency of exacerbations, such as a lack of improvement or worsening of symptoms or functional status.3 For example, the addition of a second bronchodilator is recommended for a GOLD B patient with continued breathlessness on a single bronchodilator, and escalating from 1 to 2 long-acting bronchodilators is recommended for GOLD C patients with persistent exacerbations despite monotherapy with a LABA or LAMA. LAMA/LABA combinations that are currently approved for the treatment of COPD by the US Food and Drug Administration are umeclidinium/vilanterol, tiotropium/olodaterol, glycopyrrolate/formoterol, and glycopyrrolate/indacaterol.27-30

For patients with high symptom burden (mMRC ≥2, CAT ≥10) experiencing frequent exacerbations, defined as 2 or more exacerbations per year, or 1 or more exacerbations per year that lead to a hospitalization (ie, GOLD D patients), LAMA/LABA is recommended as first-choice treatment. A recent study showed LAMA/LABA to be superior to ICS/LABA for preventing exacerbations; while it should be noted that the majority of exacerbations in this study were mild, LAMA/LABA was also found to be significantly more effective at reducing exacerbations classed as moderate or severe than ICS/LABA.31 However, these findings may not be broadly generalizable, owing to limitations associated with the study’s exclusion criteria and the high discontinuation rate reported during the study’s run-in phase, which may have introduced a selection bias.31

ICS/LABA may be considered for treating persistent exacerbations in some GOLD C patients, and may be first choice in GOLD D patients with asthma-like features, or possibly high blood eosinophil counts.3 Patients who remain symptomatic on LAMA/LABA may also be considered for triple therapy (ICS/LAMA/LABA), as per the GOLD recommendations.3 Care must be taken to use ICS appropriately, as ICS treatment may increase a patient’s risk of developing pneumonia, although risk profiles for pneumonia vary depending on the ICS treatment selected.32 Increased risk of other adverse effects associated with ICS treatment should also be considered, including oral candidiasis (odds ratio [OR], 2.65; 95% confidence interval [CI], 2.03–3.46 [note, oral candidiasis can be avoided by mouth-rinsing33]), hoarse voice (OR, 1.95; 95% CI, 1.41–2.70), and skin bruising (OR, 1.63; 95% CI, 1.31–2.03) compared with placebo in patients with COPD.21 Nonetheless, use of ICS is not associated with a mortality risk,34 and a 2017 study by Crim et al reported that the risk of pneumonia was not increased with ICS compared with placebo in patients with moderate airflow limitation who had/were at high risk of cardiovascular disease.35 Physicians should therefore consider both the potential risks and benefits of ICS before prescribing them to patients with COPD.

While careful consideration of ICS is warranted, ICS/LABA combinations are often prescribed inappropriately in many patients with COPD in clinical practice, including those at low exacerbation risk.15 Treatment de-escalation by stopping ICS may be appropriate in patients receiving ICS/LAMA/LABA who suffer from fewer than 2 exacerbations per year (ie, receiving ICS inappropriately),36 or in those who continue to experience persistent exacerbations despite ICS.3 The use of systemic steroids in stable COPD is not recommended.37

At any stage of disease, patients may benefit from a referral by primary care to a pulmonologist for further evaluation.38 Reasons include uncertain diagnosis, severe COPD, assessment for oxygen therapy, trouble finding or referring to pulmonary rehabilitation, and COPD in patients younger than 40 years of age (who may be suffering from α1-antitrypsin deficiency).38 Referring patients with significant emphysema or other co-existing lung diseases also allows evaluation for surgical interventions such as lung transplantation, lung volume reduction surgery (LVRS), or other therapies.

Patients with COPD may gain particular benefit from comanagement by primary care physicians and pulmonologists.39 For example, primary care physicians may require guidance from pulmonologists regarding the management of patients with severe disease whose therapy requirements are becoming more complex. Similarly, pulmonologists may not be comfortable managing the comorbidities often encountered in COPD (eg, anxiety and depression), so would require support from the primary care physician to provide the patients with effective, holistic management.