Transient neurologic syndromes: A diagnostic approach

ABSTRACT

Clinicians are often confronted with patients who have transient neurologic symptoms lasting seconds to hours. In many of these patients, their symptoms have gone away or returned to baseline by the time of evaluation, making the diagnosis even more challenging. Elements such as correlation of symptoms with vascular territory, prodromes, triggers, motor symptoms, confusion, and sleep behavior can guide the diagnostic workup.

KEY POINTS

- Transient ischemic attack, migraine aura, and partial seizures are common and often can be differentiated by their distinctive symptoms.

- Episodes of confusion in a patient with diabetes raise the possibility of hypoglycemic encephalopathy; other possibilities include hyperventilation syndrome and transient global amnesia.

- Daytime sleepiness in a young patient may be due to narcolepsy or parasomnias.

Transient global amnesia

Transient global amnesia usually strikes older patients (50 to 70 years old) in the setting of an acute physical or emotional stressor. There is also a correlation between transient global amnesia and migraine, with studies showing migraineurs are at higher risk than the general population.41 Despite common clinical concerns, there is no relationship between transient global amnesia and stroke.42

Transient global amnesia is defined by acute transient anterograde amnesia (coding of new memories). To try to reorient themselves, patients will repeatedly ask questions such as “What day is it?” or “Why are we here?” Retrograde memories, especially long-standing ones, are usually well preserved. The patient’s cognition is otherwise intact, and there are no other focal neurologic symptoms. The event usually lasts 2 to 24 hours and resolves without sequelae.43,44 Afterward, patients remember the event only poorly, which supports the notion that they cannot code new memories.

Confusional episodes: Discussion

Evaluating confusional episodes can be time-consuming and vexing. The subjective nature of the symptoms and the vast differential diagnosis can be overwhelming. Subtle clinical details can help formulate an appropriate evaluation.

Hypoglycemia can produce bizarre neurologic symptoms. Most cases of hypoglycemia produce an exaggerated sympathetic response, though this is blunted in people with longstanding diabetes. In addition, there should be a temporal association with meals, insulin doses, or both.

Transient global amnesia usually occurs with acute stressors and produces a confusional state. These episodes rarely recur, and the patient cannot provide much history regarding the episode secondary to the anterograde amnesia.

Table 2 summarizes the clinical findings associated with hypoglycemic encephalopathy, hyperventilation syndrome, and transient global amnesia.

Back to our patient

In our patient, the likely diagnosis is hyperventilation syndrome, even though we don’t know if her respiratory rate is increased during attacks. Some patients lack awareness of their breathing or are too distracted by the vague symptoms to have insight into the true cause. The cramps and contractions in the hands are a specific feature of the disease and can be accompanied by confusion.

SLEEP DISORDERS

A 17-year-old boy with a history of depression and anxiety presents to his pediatrician because he has had difficulty staying awake in school over the past year. His sleepiness has gradually worsened over the last few months and has taken a toll on his grades, leading to discord in his family. Over the past month he has had some difficulty holding his head up during arguments with friends. He does not lose consciousness during these events but is described as “unresponsive.” He describes vivid dreams when going to sleep that have startled him awake at times. His family history is positive for somnambulism on his father’s side.

Does this patient have a sleep disorder, and if so, which one?

Narcolepsy

Narcolepsy is defined by excessive daytime sleepiness, cataplexy, hypnagogic hallucination, and sleep paralysis. It is more common in men but its prevalence varies widely by geographic region, supporting an underlying interplay between genetics and environment.45

Sleep attacks or excessive daytime sleepiness are the cardinal features of narcolepsy. The dissociation between the sleep-wake cycle is evident with rapid transition into rapid-eye-movement (REM) sleep during these sleep attacks. This results in a “refreshing nap” that commonly involves vivid dreams. These episodes occur about 3 to 5 times per day, varying in duration from a few minutes to hours.46

Cataplexy is very specific feature of narcolepsy. Triggered by strong emotion, the body loses skeletal muscle tone except for the diaphragm and ocular muscles. The patient does not lose consciousness and remains aware of his or her environment. Of note, the loss of tone does not need to be dramatic. The hypotonia can manifest as jaw-dropping or head-nodding. The paralysis is related to prolonged REM atonia and impaired transition from sleep to wakefulness.47 Hypnagogic hallucination and sleep paralysis can occur, together with vivid visual hallucinations.

Parasomnias: Somnambulism and night terrors

Most non-REM parasomnias occur in childhood and diminish in adulthood. Two of the most common disorders are sleepwalking (somnambulism) and night terrors. Both are characterized by arousal from slow-wave sleep and are commonly associated with sedating medication, sleep deprivation, or psychopathology.

In somnambulism, patients exhibit complex motor behavior without interaction with their environment. Most have little recollection of the event.48 Sleep terrors produce a more intense reaction. The patient erupts out of sleep with profound terror, confusion, and autonomic changes. Interestingly, the patient can normally fall right back into sleep after the event.49–51

Back to our patient

Excessive daytime sleepiness and generalized fatigue are commonly encountered in outpatients. They can be frustrating because in many cases, no clear etiology can be discovered.52

This patient has several risk factors for parasomnias. His history of anxiety and depression in the setting of recent stressors sets the stage for night terrors. In addition, like many patients with parasomnias, he has a family history of sleep disorders. His vivid dreams make night terrors possible, but without the stark sympathetic activation it is a less likely diagnosis. It also does not account for the other symptoms he describes.

Our patient’s excessive daytime sleepiness interfering with daily activities, cataplexy, and hypnagogic hallucinations support the diagnosis of narcolepsy. This case highlights the variable weakness experienced during a cataplexy attack. It can range from a simple head droop to complete paralysis. Subtle findings require specific probing by the clinician. Patients with narcolepsy typically present in their late teens to early adulthood, but the cataplexy attacks may develop later in the disease course.

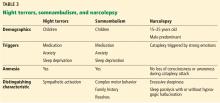

Table 3 summarizes the clinical findings associated with night terrors, somnambulism, and narcolepsy.