Transient neurologic syndromes: A diagnostic approach

ABSTRACT

Clinicians are often confronted with patients who have transient neurologic symptoms lasting seconds to hours. In many of these patients, their symptoms have gone away or returned to baseline by the time of evaluation, making the diagnosis even more challenging. Elements such as correlation of symptoms with vascular territory, prodromes, triggers, motor symptoms, confusion, and sleep behavior can guide the diagnostic workup.

KEY POINTS

- Transient ischemic attack, migraine aura, and partial seizures are common and often can be differentiated by their distinctive symptoms.

- Episodes of confusion in a patient with diabetes raise the possibility of hypoglycemic encephalopathy; other possibilities include hyperventilation syndrome and transient global amnesia.

- Daytime sleepiness in a young patient may be due to narcolepsy or parasomnias.

Partial seizure

Partial seizure produces a diverse range of stereotypical symptoms due to focal abnormal neuronal activation. The aberrant electrical firing generates positive symptoms involving the motor, sensory, or visual pathway. A history of trauma, neurosurgical intervention, central nervous system infection, stroke, or other seizure foci can suggest this diagnosis. Other prodromal clues include abdominal discomfort, sense of detachment, déjà vu, or jamais vu.26

During a seizure, there may be a progression of positive symptoms similar to what happens in migraine aura, because both represent cortical spread and depression.

Involvement of the motor pathway may produce tonic (stiffening) or clonic (twitching) movement. Other common motor abnormalities include automatisms such as lip smacking, chewing, and hand gestures (picking, fidgeting, fumbling).27

Epileptic discharges in the sensory cortex commonly cause paresthesias or distortion of a sensory input. Visual symptoms may be more complex. In occipital epilepsy, circular phenomena with a colored pattern are common, which contrasts with the photopsia (flashes of light) or fortification (a bright zigzag of lines resembling a fort) seen in migraines.28

Autonomic or somatosensory symptoms can also occur.

Todd paralysis, also called transient postictal paralysis, occurs in only 13% of seizures but can linger for 0.5 to 36 hours.29,30 This weakness is most pronounced within the affected region after a partial seizure.

In general, focal seizures are often stereotyped with positive neurologic features, usually last a few minutes, and resolve fully. These episodes may cause an arrest in activity but not usually loss of consciousness unless the epileptic discharge secondarily generalizes into the adjacent hemisphere.

A common differential diagnosis encountered during an epilepsy workup is psychogenic nonepileptic seizures. Nonepileptic seizures consist of transient, abnormal movements, sensation, or cognition but lack ictal electroencephalographic changes. This is a specifically challenging patient population, with high healthcare utilization and high risk for iatrogenic harm. In addition, on average, diagnosis can take years to establish and usually requires referral to a tertiary care facility.31,32

The big 3: Back to our patient

Our patient’s vascular risk factors, transient symptoms, and language involvement support the diagnosis of TIA. A feature that points away from the diagnosis of TIA is the gradual onset of positive neurologic symptoms. This pattern is not consistent with neuronal ischemia.

Also, our patient had a repetitive, stereotypical pattern of symptoms, which supports including partial seizures in the differential diagnosis. On the other hand, her lack of risk factors for seizure (a history of febrile seizures, developmental delay, trauma, or infection) would make this diagnosis less likely. Also pointing away from the diagnosis of seizures are her lack of typical prodromal symptoms, the length of the events, and the postevent headache.

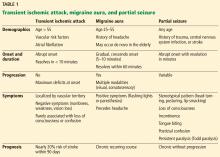

Table 1 summarizes the clinical findings associated with TIA, migraine, and partial seizure.

EPISODES OF CONFUSION

A 35-year-old woman with a history of depression, anxiety, and poorly controlled type 1 diabetes presents to the clinic after several weeks of episodes of confusion, usually accompanied by paresthesias in both hands, dizziness, and palpitations. In each episode, soon after the symptoms began, she had painful cramps in her hand. The symptoms fully resolved within 10 minutes without sequelae.

Questioned further, the patient describes the confusion as a “mental haze” but denies frank disorientation. She has not kept a log of her blood sugar levels but has not noticed a temporal relationship with regard to her meals or insulin injections.

What are the possible causes of these episodes?

Hypoglycemic encephalopathy

Hypoglycemia is common in most people with diabetes, who have been reported to suffer from 62 to 320 severe hypoglycemic episodes in their lifetime.33,34 The neurologic consequences can be devastating in these severe cases.

During mild to moderate drops in the glucose level, generalized symptoms stem from sympathetic activation. These include generalized anxiety, tremor, palpitations, and sweating. Focal symptoms such as unilateral weakness have also been reported.35,36

Unfortunately, people with long-standing diabetes have a blunted response to epinephrine that reduces their sensitivity to hypoglycemia, placing them at high risk of permanent neurologic damage. This can lead to seizures and coma, as the hypoglycemia has a greater effect on cortical and subcortical structures (highly metabolic areas) than on the brainstem. Thus, respiratory and cardiovascular function is maintained but cerebral function is abnormal. If this state is prolonged, brain death can occur.37,38

Hyperventilation syndrome

Hyperventilation syndrome is not well characterized. Most think of it as synonymous with an underlying psychopathology, but there is evidence to suggest it can occur without underlying anxiety.

There is no clear mechanism, but it is hypothesized that diminished carbon dioxide levels lead to cerebral vasoconstriction. This may lead to reduced cerebral blood flow, causing dizziness, lightheadedness, or vertigo.39 Appendicular symptoms including paresthesias, carpopedal spasm, or tetany have been core features since the syndrome was first described in the early 1900s.40

Though the disorder has rather nonspecific features, it can be easily reproduced in the clinical setting by asking the patient to breathe deeply and rapidly. This can help confirm the underlying diagnosis and also reassure the patient that the underlying pathology is not life-threatening and that he or she has some control over the disease.