Navigating the anticoagulant landscape in 2017

ABSTRACT

Several questions remain regarding anticoagulant management: What is the best strategy for managing acute venous thromboembolism? How should patients on a direct oral anticoagulant or on warfarin be managed when they need elective surgery? When is heparin bridging necessary?

KEY POINTS

- Venous thromboembolism has a myriad of clinical presentations, warranting a holistic management approach that incorporates multiple antithrombotic management strategies.

- A direct oral anticoagulant is an acceptable treatment option in patients with submassive venous thromboembolism, whereas catheter-directed thrombolysis should be considered in patients with iliofemoral deep vein thrombosis, and low-molecular-weight heparin in patients with cancer-associated thrombosis.

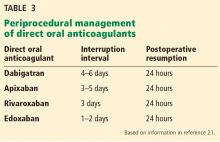

- Perioperative management of direct oral anticoagulants should be based on the pharmacokinetic properties of the drug, the patient’s renal function, and the risk of bleeding posed by the surgery or procedure.

- Perioperative heparin bridging can be avoided in most patients who have atrial fibrillation or venous thromboembolism, but should be considered in most patients with a mechanical heart valve.

Bridging in patients with prior venous thromboembolism

Even less evidence is available for periprocedural management of patients who have a history of venous thromboembolism. No randomized controlled trials exist evaluating bridging vs no bridging. In 1 cohort study in which more than 90% of patients had had thromboembolism more than 3 months before the procedure, the rate of recurrent venous thromboembolism without bridging was less than 0.5%.14

It is reasonable to bridge patients who need anticoagulant interruption within 3 months of diagnosis of a deep vein thrombosis or pulmonary embolism, and to consider using a temporary inferior vena cava filter for patients who have had a clot who need treatment interruption during the initial 3 to 4 weeks after diagnosis.

Practice guidelines: Perioperative anticoagulation

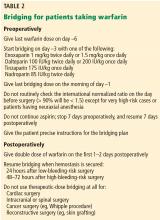

Guidance for preoperative and postoperative bridging for patients taking warfarin is summarized in Table 2.

CARDIAC PROCEDURES

For patients facing a procedure to implant an implantable cardioverter-defibrillator (ICD) or pacemaker, a procedure-specific concern is the avoidance of pocket hematoma.

Patients on warfarin: Do not bridge

The BRUISE CONTROL-1 trial (Bridge or Continue Coumadin for Device Surgery Randomized Controlled Trial)19 randomized patients undergoing pacemaker or ICD implantation to either continued anticoagulation therapy and not bridging (ie, continued warfarin so long as the international normalized ratio was < 3) vs conventional bridging treatment (ie, stopping warfarin and bridging with low-molecular-weight heparin). A clinically significant device-pocket hematoma occurred in 3.5% of the continued-warfarin group vs 16.0% in the heparin-bridging group (P < .001). Thromboembolic complications were rare, and rates did not differ between the 2 groups.

Results of the BRUISE CONTROL-1 trial serve as a caution to at least not be too aggressive with bridging. The study design involved resuming heparin 24 hours after surgery, which is perhaps more aggressive than standard practice. In our practice, we wait at least 24 hours to reinstate heparin after minor surgery, and 48 to 72 hours after surgery with higher bleeding risk.

These results are perhaps not surprising if one considers how carefully surgeons try to control bleeding during surgery for patients taking anticoagulants. For patients who are not on an anticoagulant, small bleeding may be less of a concern during a procedure. When high doses of heparin are introduced soon after surgery, small concerns during surgery may become big problems afterward.

Based on these results, it is reasonable to undertake device implantation without interruption of a vitamin K antagonist such as warfarin.

Patients on direct oral anticoagulants: The jury is still out

The similar BRUISE CONTROL-2 trial is currently under way, comparing interruption vs continuation of dabigatran for patients undergoing cardiac device surgery.

In Europe, surgeons are less concerned than those in the United States about operating while a patient is on anticoagulant therapy. But the safety of this practice is not backed by strong evidence.

Direct oral anticoagulants: Consider pharmacokinetics

Direct oral anticoagulants are potent and fast-acting, with a peak effect 1 to 3 hours after intake. This rapid anticoagulant action is similar to that of bridging with low-molecular-weight heparin, and caution is needed when administering direct oral anticoagulants, especially after major surgery or surgery with a high bleeding risk.

Frost et al20 compared the pharmacokinetics of apixaban (with twice-daily dosing) and rivaroxaban (once-daily dosing) and found that peak anticoagulant activity is faster and higher with rivaroxaban. This is important, because many patients will take their anticoagulant first thing in the morning. Consequently, if patients require any kind of procedure (including dental), they should skip the morning dose of the direct oral anticoagulant to avoid having the procedure done during the peak anticoagulant effect, and they should either not take that day’s dose or defer the dose until the evening after the procedure.

MANAGING SURGERY FOR PATIENTS ON A DIRECT ORAL ANTICOAGULANT

Case 3: An elderly woman on apixaban facing surgery

Let us imagine that our previous patient takes apixaban instead of warfarin. She is 75 years old, has atrial fibrillation, and is about to undergo elective colon resection for cancer. One doctor advises her to simply stop apixaban for 2 days, while another says she should go off apixaban for 5 days and will need bridging. Which plan is best?

In the perioperative setting, our goal is to interrupt patients’ anticoagulant therapy for the shortest time that results in no residual anticoagulant effect at the time of the procedure.

They further recommend that if the risk of venous thromboembolism is high, low-molecular-weight heparin bridging should be done while stopping the direct oral anticoagulant, with the heparin discontinued 24 hours before the procedure. This recommendation seems counterintuitive, as it is advising replacing a short-acting anticoagulant with low-molecular-weight heparin, another short-acting anticoagulant.

The guidelines committee was unable to provide strength and grading of their recommendations, as too few well-designed studies are available to support them. The doctor in case 3 who advised stopping apixaban for 5 days and bridging is following the guidelines, but without much evidence to support this strategy.