Navigating the anticoagulant landscape in 2017

ABSTRACT

Several questions remain regarding anticoagulant management: What is the best strategy for managing acute venous thromboembolism? How should patients on a direct oral anticoagulant or on warfarin be managed when they need elective surgery? When is heparin bridging necessary?

KEY POINTS

- Venous thromboembolism has a myriad of clinical presentations, warranting a holistic management approach that incorporates multiple antithrombotic management strategies.

- A direct oral anticoagulant is an acceptable treatment option in patients with submassive venous thromboembolism, whereas catheter-directed thrombolysis should be considered in patients with iliofemoral deep vein thrombosis, and low-molecular-weight heparin in patients with cancer-associated thrombosis.

- Perioperative management of direct oral anticoagulants should be based on the pharmacokinetic properties of the drug, the patient’s renal function, and the risk of bleeding posed by the surgery or procedure.

- Perioperative heparin bridging can be avoided in most patients who have atrial fibrillation or venous thromboembolism, but should be considered in most patients with a mechanical heart valve.

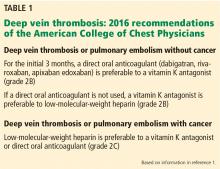

Role of direct oral anticoagulants

The availability of direct oral anticoagulants has generated interest in defining their therapeutic role in patients with venous thromboembolism.

In a meta-analysis5 of major trials comparing direct oral anticoagulants and vitamin K antagonists such as warfarin, no significant difference was found for the risk of recurrent venous thromboembolism or venous thromboembolism-related deaths. However, fewer patients experienced major bleeding with direct oral anticoagulants (relative risk 0.61, P = .002). Although significant, the absolute risk reduction was small; the incidence of major bleeding was 1.1% with direct oral anticoagulants vs 1.8% with vitamin K antagonists.

The main advantage of direct oral anticoagulants is greater convenience for the patient.

WHICH PATIENTS ON WARFARIN NEED BRIDGING PREOPERATIVELY?

Many patients still take warfarin, particularly those with atrial fibrillation, a mechanical heart valve, or venous thromboembolism. In many countries, warfarin remains the dominant anticoagulant for stroke prevention. Whether these patients need heparin during the period of perioperative warfarin interruption is a frequently encountered scenario that, until recently, was controversial. Recent studies have helped to inform the need for heparin bridging in many of these patients.

Case 2: An elderly woman on warfarin facing cancer surgery

A 75-year-old woman weighing 65 kg is scheduled for elective colon resection for incidentally found colon cancer. She is taking warfarin for atrial fibrillation. She also has hypertension and diabetes and had a transient ischemic attack 10 years ago.

One doctor told her she needs to be assessed for heparin bridging, but another told her she does not need bridging.

The default management should be not to bridge patients who have atrial fibrillation, but to consider bridging in selected patients, such as those with recent stroke or transient ischemic attack or a prior thromboembolic event during warfarin interruption. However, decisions about bridging should not be made on the basis of the CHADS2 score alone. For the patient described here, I would recommend not bridging.

Complex factors contribute to stroke risk

Stroke risk for patients with atrial fibrillation can be quickly estimated with the CHADS2 score, based on:

- Congestive heart failure (1 point)

- Hypertension (1 point)

- Age at least 75 (1 point)

- Diabetes (1 point)

- Stroke or transient ischemic attack (2 points).

Our patient has a score of 5, corresponding to an annual adjusted stroke risk of 12.5%. Whether her transient ischemic attack of 10 years ago is comparable in significance to a recent stroke is debatable and highlights a weakness of clinical prediction rules. Moreover, such prediction scores were developed to estimate the long-term risk of stroke if anticoagulants are not given, and they have not been assessed in a perioperative setting where there is short-term interruption of anticoagulants. Also, the perioperative milieu is associated with additional factors not captured in these clinical prediction rules that may affect the risk of stroke.

Thus, the risk of perioperative stroke likely involves the interplay of multiple factors, including the type of surgery the patient is undergoing. Some factors may be mitigated:

- Rebound hypercoagulability after stopping an oral anticoagulant can be prevented by intraoperative blood pressure and volume control

- Elevated biochemical factors (eg, D-dimer, B-type natriuretic peptide, troponin) may be lowered with perioperative aspirin therapy

- Lipid and genetic factors may be mitigated with perioperative statin use.

Can heparin bridging also mitigate the risk?

Bridging in patients with atrial fibrillation

Most patients who are taking warfarin are doing so because of atrial fibrillation, so most evidence about perioperative bridging was developed in such patients.

The BRIDGE trial (Bridging Anticoagulation in Patients Who Require Temporary Interruption of Warfarin Therapy for an Elective Invasive Procedure or Surgery)6 was the first randomized controlled trial to compare a bridging and no-bridging strategy for patients with atrial fibrillation who required warfarin interruption for elective surgery. Nearly 2,000 patients were given either low-molecular-weight heparin or placebo starting 3 days before until 24 hours before a procedure, and then for 5 to 10 days afterwards. For all patients, warfarin was stopped 5 days before the procedure and was resumed within 24 hours afterwards.

A no-bridging strategy was noninferior to bridging: the risk of perioperative arterial thromboembolism was 0.4% without bridging vs 0.3% with bridging (P = .01 for noninferiority). In addition, a no-bridging strategy conferred a lower risk of major bleeding than bridging: 1.3% vs 3.2% (relative risk 0.41, P = .005 for superiority).

Although the difference in absolute bleeding risk was small, bleeding rates were lower than those seen outside of clinical trials, as the bridging protocol used in BRIDGE was designed to minimize the risk of bleeding. Also, although only 5% of patients had a CHADS2 score of 5 or 6, such patients are infrequent in clinical practice, and BRIDGE did include a considerable proportion (17%) of patients with a prior stroke or transient ischemic attack who would be considered at high risk.

Other evidence about heparin bridging is derived from observational studies, more than 10 of which have been conducted. In general, they have found that not bridging is associated with low rates of arterial thromboembolism (< 0.5%) and that bridging is associated with high rates of major bleeding (4%–7%).7–12

Bridging in patients with a mechanical heart valve

Warfarin is the only anticoagulant option for patients who have a mechanical heart valve. No randomized controlled trials have evaluated the benefits of perioperative bridging vs no bridging in this setting.

Observational (cohort) studies suggest that the risk of perioperative arterial thromboembolism is similar with or without bridging anticoagulation, although most patients studied were bridged and those not bridged were considered at low risk (eg, with a bileaflet aortic valve and no additional risk factors).13 However, without stronger evidence from randomized controlled trials, bridging should be the default management for patients with a mechanical heart valve. In our practice, we bridge most patients who have a mechanical heart valve unless they are considered to be at low risk, such as those who have a bileaflet aortic valve.