A minimally invasive treatment for early GI cancers

ABSTRACT

Endoscopic submucosal dissection (ESD) allows curative resection of early malignant gastrointestinal (GI) lesions, potentially avoiding open surgery. Unfortunately, awareness of this technique is low, and many patients undergo surgery without consideration of ESD. This article reviews the indications for ESD and its advantages and limitations, and guides internists in their approach to patients with early GI cancer.

KEY POINTS

- ESD is a minimally invasive endoscopic technique with curative potential for patients with superficial GI neoplasia.

- ESD preserves the integrity of the organ while achieving curative resection of large neoplasms.

- ESD is indicated rather than surgery in patients with early GI lesions with a negligible risk of lymph node metastasis.

- Complications of the procedure include bleeding, perforation, and stenosis. Most of these respond to endoscopic treatment.

- Successful ESD requires supportive teamwork among internists, gastroenterologists, pathologists, and surgeons.

COLORECTAL CANCER

Indications for ESD for colorectal cancer in the East

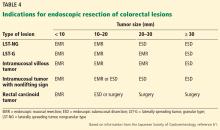

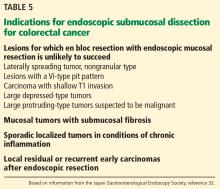

Colon cancer is one of the leading causes of cancer-related deaths worldwide.58 Since ESD has been found to be effective and safe in treating gastric cancer, it has also been used to remove large colorectal tumors.59 However, ESD is not universally accepted in the treatment of colorectal neoplasms due to its greater technical difficulty, longer procedural time, and higher risk of perforating the thinner colonic wall compared with EMR.21,60

Outcomes for colorectal cancer

Tumor size of 50 mm or larger is a risk factor for complications, while a high procedure volume at the center is a protective factor.60

Endoscopic treatment of colorectal cancer: The Western perspective

EMR is the gold standard for removal of superficial colorectal lesions. However, ESD can be considered if there is suspicion of superficial submucosal invasion, especially for lesions larger than 20 mm that cannot be resected en bloc by EMR.32 ESD can also be used for fibrotic lesions not amenable to complete EMR removal, or as a salvage procedure after recurrence after EMR.67 Proper selection of cases is critical.1

Patients who have a superficial colonic lesion should be evaluated by means of high-definition endoscopy and chromoendoscopy to assess the mucosal pattern and establish feasibility of endoscopic resection. If submucosal invasion is suspected, staging with endoscopic ultrasonography or magnetic resonance imaging should be considered.5

FOLLOW-UP AFTER ESD

Endoscopic surveillance after the procedure is recommended, given the persistent risk of metachronous cancer after curative ESD due to its organ-sparing quality.68 Surveillance endoscopy aims to achieve early detection and subsequent endoscopic resection of metachronous lesions.

Histopathologic evaluation assessing the presence of malignant cells in the margins of a resected sample is mandatory for determining the next step in treatment. If margins are negative, follow-up endoscopy can be done every 6 to 12 months. If margins are positive, the approach includes surgery, reattempting ESD or endoscopic surveillance in 3 or 6 months.3,32 Although the surveillance strategy varies according to individual risk of metachronous cancer, it should be continued indefinitely.68

COMPLICATIONS OF ESD

The most common procedure-related complications of ESD are bleeding, perforation, and stricture. Most intraprocedural adverse events can be managed endoscopically.69

Bleeding

Most bleeding occurs during the procedure or early after it and can be controlled with electrocautery.49,69 No episodes of massive bleeding, defined as causing clinical symptoms and requiring transfusion or surgery, have been reported.20,43,55

In gastric ESD, delayed bleeding rates have ranged from 0 to 15.6%.69 Bleeding may be prevented with endoscopic coagulation of visible vessels after dissection has been completed and by proton pump inhibitor therapy.70,71 Excessive coagulation should be avoided to lower the risk of perforation.33

In colorectal ESD the bleeding rate has been reported to be 2.2%; applying coagulation to an area where a blood vessel is suspected before cutting (precoagulation) may prevent subsequent bleeding.21

Perforation

For gastric ESD, perforation rates range from 1.2% to 5.2%.69 Esophageal perforation rates can be up to 4%.49 In colorectal ESD, perforation rates have been reported to be 1.6% to 6.6%.60,72

Although most of the cases were successfully managed with conservative treatment, some required emergency surgery.60,73

Strictures

In a case series of 532 patients undergoing gastric ESD, stricture was reported in 5 patients, all of whom presented with obstructive symptoms.74 Risk factors for post-ESD gastric stenosis are a mucosal defect with a circumferential extent of more than three-fourths or a longitudinal extent of more than 5 cm.75

Strictures are common after esophageal ESD, with rates ranging from 2% to 26%. The risk is higher when longer segments are removed or circumferential resection is performed. As previously mentioned, this complication may be reduced with ingestion or injection of steroids after the procedure.53,54

Surprisingly, ESD of large colorectal lesions involving more than three-fourths of the circumference of the rectum is rarely complicated by stenosis.76