Sexual dysfunction in women: Can we talk about it?

ABSTRACT

Sexual dysfunction in women is common and often goes unreported and untreated. Its management is part of patient-centered primary care. Primary care providers are uniquely positioned to identify and assess sexual health concerns of their patients, provide reassurance regarding normal sexual function, and treat sexual dysfunction or refer as appropriate.

KEY POINTS

- Sexual dysfunction in women is complex and often multifactorial and has a significant impact on quality of life.

- Primary care providers can assess the problem, provide education on sexual health and normal sexual functioning, and manage biological factors affecting sexual function, including genitourinary syndrome of menopause in postmenopausal women and antidepressant-induced sexual dysfunction.

- Treatment may require a multidisciplinary team, including a psychologist or sex therapist to manage the psychological, sociocultural, and relational factors affecting a woman’s sexual health, and a physical therapist to manage pelvic floor disorders.

CATEGORIES OF SEXUAL DYSFUNCTION IN WOMEN

The World Health Organization defines sexual health as “a state of physical, emotional, mental, and social well-being in relation to sexuality” and “not merely the absence of disease, dysfunction, or infirmity.”13

The Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fifth Edition (DSM-5),14 published in 2013, defines three categories of sexual dysfunction in women:

- Female sexual interest and arousal disorder

- Female sexual orgasmic disorder

- Genitopelvic pain/penetration disorder.

To meet the diagnosis of any of these, symptoms must:

- Persist for at least 6 months

- Occur in 75% to 100% of sexual encounters

- Be accompanied by personal distress

- Not be related to another psychological or medical condition, medication or substance use, or relationship distress.

Sexual problems may be lifelong or acquired after a period of normal functioning, and may be situational (present only in certain situations) or generalized (present in all situations).

Female sexual interest and arousal disorder used to be 2 separate categories in earlier editions of the DSM. Proponents of merging the 2 categories in DSM-5 cited several reasons, including difficulty in clearly distinguishing desire from other motivations for sexual activity, the relatively low reporting of fantasy in women, the complexity of distinguishing spontaneous from responsive desire, and the common co-occurrence of decreased desire and arousal difficulties.15

Other experts, however, have recommended keeping the old, separate categories of hypoactive sexual desire disorder and arousal disorder.16 The recommendation to preserve the diagnostic category of hypoactive sexual desire disorder is based on robust observational and registry data, as well as the results of randomized controlled trials that used the old criteria for hypoactive sexual desire disorder to assess responses to pharmacologic treatment of this condition.17–19 In addition, this classification as a separate and distinct diagnosis is consistent with the nomenclature used in the International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems, 10th Revision and was endorsed by the International Consultation on Sexual Medicine in 2015.16

HOW TO ASK ABOUT SEXUAL HEALTH

Assessment of sexual health concerns should be a part of a routine health examination, particularly after childbirth and other major medical, surgical, psychological, and life events. Women are unlikely to bring up sexual health concerns with their healthcare providers, but instead hope that their providers will bring up the topic.20

Barriers to the discussion include lack of provider education and training, patient and provider discomfort, perceived lack of time during an office visit, and lack of approved treatments.21,22 Additionally, older women are less likely than men to discuss sexual health with their providers.23 Other potential barriers to communication include negative societal attitudes about sexuality in women and in older individuals.24,25 To overcome these barriers:

Legitimize sexual health as an important health concern and normalize its discussion as part of a routine clinical health assessment. Prefacing a query about sexual health with a normalizing and universalizing statement can help: eg, “Many women going through menopause have concerns about their sexual health. Do you have any sexual problems or concerns?” Table 1 contains examples of questions to use for initial screening for sexual dysfunction.22,26

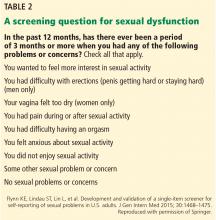

Flynn et al27 proposed a validated single-question checklist to screen for sexual dysfunction that is an efficient way to identify specific sexual concerns, guide selection of interventions, and facilitate patient-provider communication (Table 2).

Don’t judge and don’t make assumptions about sexuality and sexual practices.

Assure confidentiality.

Use simple, direct language that is appropriate for the patient’s age, ethnicity, culture, and level of health literacy.3

Take a thorough history (sexual and reproductive, medical-surgical, and psychosocial).