Malignant Pleural Effusion: Evaluation and Diagnosis

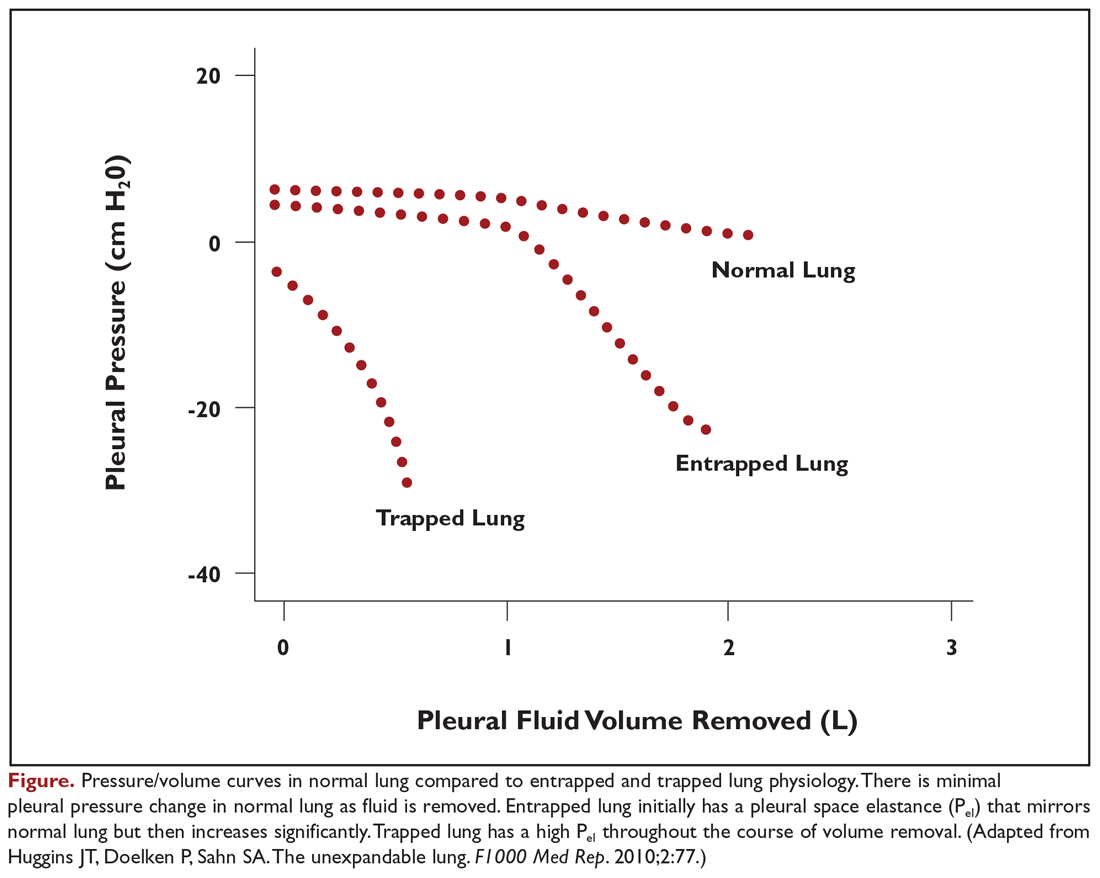

A patient’s degree of symptom palliation and physiologic improvement in response to large-volume fluid removal is important to assess as these are important clinical factors that will influence management decision-making. Upwards of 50% of patients will not have significant palliation because they may be symptom-limited by other comorbid conditions, generalized deconditioning, or incomplete lung re-expansion. Presence of impaired lung compliance during fluid removal is also important to recognize. A trapped lung refers to a lung that cannot expand completely after removal of pleural fluid. Trapped lung may result from pleural-based malignancies or metastases, loculations and adhesions, or bronchial obstruction. Trapped lung is associated with high elastance (Pel) affecting pleural pressure-volume relationships (Figure 1). While clinically often considered together, some authors differentiate the category of incomplete lung expansion into 2 subgroups. In this context, the term trapped lung is used specifically to describe a mature, fibrous membrane that prevents lung re-expansion and is caused by a prior inflammatory pleural condition.21 Entrapped lung describes incomplete lung expansion resulting from an active disease process, such as malignancy, ongoing infection, or rheumatologic pleurisy. Differences in pleural manometry can be seen in the 2 subgroups. Pleural manometry can be helpful to monitor for the generation of high negative intrapleural pressures during fluid removal, with negative pressures in excess of –19 cm H2O being suggestive of trapped lung physiology.22 However routine use of pleural manometry has not been shown to avoid the development of procedure-related chest discomfort that develops when the lung is unable to expand in response to the removal of fluid.23

Pleural Fluid Analysis and Pleural Biopsy

While most MPEs are protein-rich exudates, approximately 2% to 5% may be transudates.24,25 MPEs often appear hemorrhagic, so a ratio of pleural fluid to blood serum hematocrit greater than 0.5 is used to distinguish a true hemothorax from bloody-appearing pleural fluid.26 The cell count may be lymphocyte-predominant, but other cell types, such as eosinophils, do not exclude malignancy.27 Fluid may have a low glucose concentration and pH as well.

Thoracentesis with pleural fluid cytology evaluation is the most common method of diagnosis. The diagnostic sensitivity of fluid cytology ranges from 62% to 90%, with variability resulting from the extent of disease and etiology of the primary malignancy.1 If the initial pleural fluid analysis is not diagnostic, repeat thoracentesis can improve the diagnostic yield, but subsequent sampling has diminishing utility. In one series, diagnosis of malignancy was made by fluid cytology analysis in 65% of patients from the initial thoracentesis, 27% from a second procedure, but only 5% from a third procedure.28 At least 50 to 60 mL of pleural fluid should be obtained for pleural fluid cytology, but analysis of significantly larger volumes may not appreciably improve diagnostic yield.29,30

In addition to diagnostic yield, adequate sample cellularity to test for genetic driver mutations has become increasingly important given the rapid development of targeted therapies that are now available. The relative paucity of malignant cells in pleural fluid compared to other types of biopsies can make MPEs difficult to analyze for molecular markers. Newer generation assays have increased sensitivity, with one series reporting that pleural fluid was sufficient in 71.4% of cases to analyze for a panel comprised of EGFR, KRAS, BRAF, ALK, and ROS1 mutations.31 Similarly, fluid analysis from patients with MPEs demonstrated that 71.3% had at least 100 tumor cells, which permitted evaluation for PD-L1, with a concordance of 0.78 when compared to matched parenchymal lung biopsies from the same patient.32

In contrast, pleural biopsy methods may be useful to increase the diagnostic yield when pleural fluid analysis is insufficient. Closed needle biopsy may marginally improve diagnostic yields for malignancy over pleural fluid analysis alone. Diagnostic sensitivity may improve with the use of point-of-care ultrasonography to guide needle placement.33,34 The true value of closed needle biopsy is seen in situations in which there is a high pretest probability to diagnose an alternative disseminated pleural process, such as in tuberculosis, where the diagnostic yield increases substantially with closed needle biopsy of the pleura.33 Otherwise, the diagnosis of lung cancer and mesothelioma is superior with visually guided pleural biopsies, such as medical thoracoscopy or video-assisted thoracoscopic surgery (VATS), with diagnostic yields over 90%.33,35 Testing for genetic driver mutations in pleural biopsies is also substantially improved, with sample adequacy of 90% to 95% for most molecular markers.36,37 Despite the advantages, pleural biopsies are generally reserved for cases when pleural fluid analysis is insufficient or when performed in conjunction with palliative therapeutic interventions due to the increased invasive nature of the procedure.