Emergency contraception: Separating fact from fiction

ABSTRACTRates of unintended pregnancy and abortion are high, yet many doctors do not feel comfortable discussing emergency contraception with patients, even in cases of sexual assault. Since the approval of ulipristal acetate (ella) for emergency contraception, there has been even more confusion and controversy. This article reviews various emergency contraceptive options, their efficacy, and special considerations for use, and will attempt to clarify myths surrounding this topic.

KEY POINTS

- Levonorgestrel-based emergency contraceptives such as Plan B One-Step, Next Choice, and generics are now available over the counter, which has the advantage of avoiding the delays and hassles of calling the doctor’s office and waiting for prescriptions. But patients still need our guidance on how and when to use emergency contraception.

- Even if patients now have easy access to over-the-counter emergency contraceptives, we physicians should take every opportunity to discuss effective contraceptive options with our patients.

- Ulipristal and copper intrauterine devices (ParaGard) are likely to be more effective than levonorgestrel and should be considered in women at highest risk of pregnancy, such as those who are obese.

- Prescribers should feel comfortable addressing tough questions about mechanisms of action, as controversies and myths about emergency contraception are regularly discussed in the media and on the Internet.

In the United States, nearly 50 million legal abortions were performed between 1973 and 2008.1 About half of pregnancies in American women are unintended, and 4 out of 10 unintended pregnancies are terminated by abortion.2 Of the women who had abortions, 54% had used a contraceptive method during the month they became pregnant.3

It is hoped that the expanded use of emergency contraception will translate into fewer abortions. However, in a 2006–2008 survey conducted by the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, only 9.7% of women ages 15 to 44 reported ever having used emergency contraception.4 (To put this figure in perspective, a similar number—about 10%—of women in this age group become pregnant in any given year, half of them unintentionally.4) Clearly, patients need to be better educated in the methods of contraception and emergency contraception.

Hospitals are not meeting the need. Pretending to be in need of emergency contraception, Harrison5 called the emergency departments of all 597 Catholic hospitals in the United States and 615 (17%) of the non-Catholic hospitals. About half of the staff she spoke to said they do not dispense emergency contraception, even in cases of sexual assault. This was the case for both Catholic and non-Catholic hospitals. Of the people she talked to who said they did not provide emergency contraception under any circumstance, only about half gave her a phone number for another facility to try, and most of these phone numbers were wrong, were for facilities that were not open on weekends, or were for facilities that did not offer emergency contraception either. This is in spite of legal precedent, which indicates that failure to provide complete post-rape counseling, including emergency contraception, constitutes inadequate care and gives a woman the standing to sue the hospital.6

Clearly, better provider education is also needed in the area of emergency contraception. The Association of Reproductive Health Professionals has a helpful Web site for providers and for patients. In addition to up-to-date information about contraceptive and emergency contraceptive choices, it provides advice on how to discuss emergency contraception with patients (www.arhp.org). We can test our own knowledge of this topic by reviewing the following questions.

WHICH PRODUCT IS MOST EFFECTIVE?

Q: True or false? Levonorgestrel monotherapy (Plan B One-Step, Next Choice) is the most effective oral emergency contraceptive.

A: False, although this statement was true before the US approval of ulipristal acetate (ella) in August 2010.

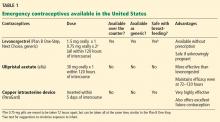

For many years levonorgestrel monotherapy has been the mainstay of emergency contraception, having replaced the combination estrogen-progestin (Yuzpe) regimen because of better tolerability and improved efficacy.7 Its main mechanism of action involves delaying ovulation. Levonorgestrel is given in two doses of 0.75 mg 12 hours apart, or as a single 1.5-mg dose (Table 1). Both formulations of levonorgestrel are available over the counter to women age 17 and older, or by prescription if they are under age 17.

However, a randomized controlled trial showed that women treated with ulipristal had about half the number of pregnancies than in those treated with levonorgestrel, with pregnancy rates of 0.9% vs 1.7%.8

HOW WIDE IS THE WINDOW OF OPPORTUNITY?

Q: True or false? Both ulipristal and levonorgestrel can be taken up to 120 hours (5 days) after unprotected intercourse. However, ulipristal maintains its effectiveness throughout this time, whereas levonorgestrel becomes less effective the longer a patient waits to take it.

A: True. Ulipristal is a second-generation selective progesterone receptor modulator. These drugs can function as agonists, antagonists, or mixed agonist-antagonists at the progesterone receptor, depending on the tissue affected. Ulipristal is given as a one-time, 30-mg dose within 120 hours of intercourse.

In a study of 1,696 women, 844 of whom received ulipristal acetate and 852 of whom received levonorgestrel, ulipristal was at least as effective as levonorgestrel when used within 72 hours of intercourse for emergency contraception, with 15 pregnancies in the ulipristal group and 22 pregnancies in the levonorgestrel group (odds ratio [OR] 0.68, 95% confidence interval [CI] 0.35–1.31]). However, ulipristal prevented significantly more pregnancies than levonorgestrel at 72 to 120 hours, with no pregnancies in the ulipristal group and three pregnancies in the levonorgestrel group.9

Because ulipristal has a long half-life (32 hours), it can delay ovulation beyond the life span of sperm, thereby extending the window of opportunity for emergency contraception. However, patients should be advised to avoid further unprotected intercourse after the use of emergency contraception. Because emergency contraception works mainly by delaying ovulation, it may increase the likelihood of pregnancy if the patient has unprotected intercourse again several days later.