The Need for Standardized Metrics to Drive Decision-making During the COVID-19 Pandemic

© 2021 Society of Hospital Medicine

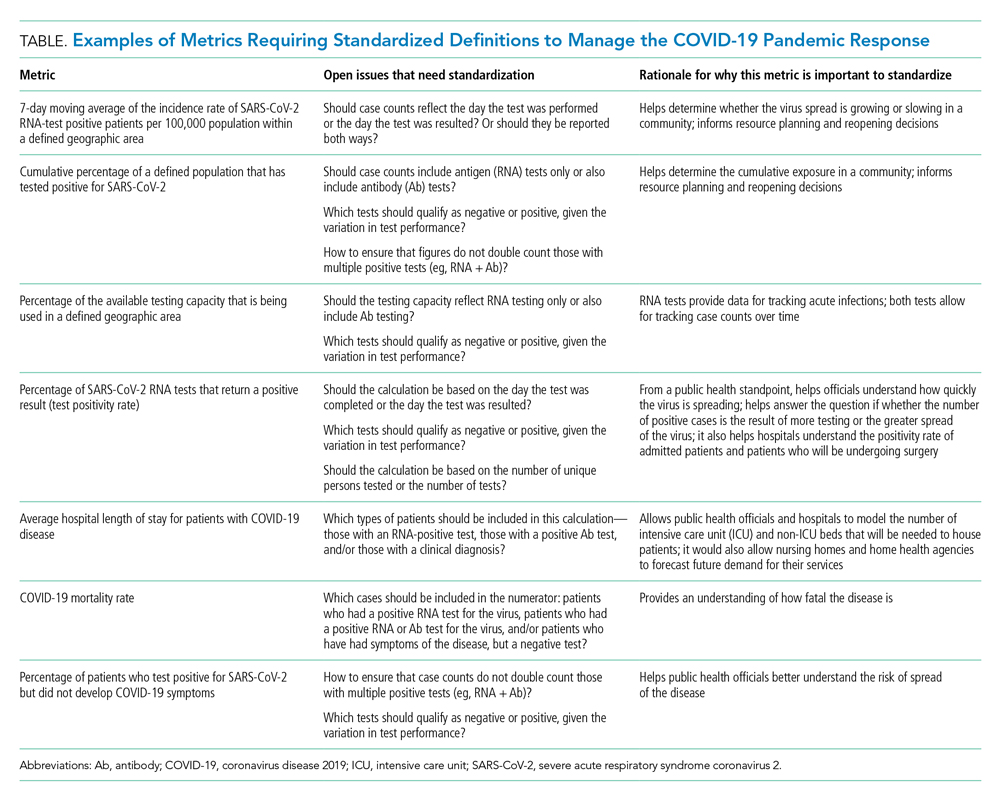

CURRENT METRICS THAT NEED STANDARDIZATION

The lack of clarity on, and politicization of, pandemic data demonstrate the need to take stock of what metrics require standardization to help public health officials and health system leaders manage the pandemic response moving forward. The Table provides examples of currently used metrics that would benefit from better standardization to inform decision-making across a broad range of settings, including public health, hospitals, physician clinics, and nursing homes. For example, a commonly referenced metric during the pandemic has been a moving average of the incidence rate of positive COVID-19 cases in a defined geographic area (eg, a state).10,11 This data point is helpful to healthcare delivery organizations for understanding the change in COVID-19 cases in their cities and states, which can inform planning on whether or not to continue elective surgeries or how many beds need to be kept in reserve status for a potential surge of hospitalizations. But there has not been a consensus around whether the reporting of COVID-19 positive tests should reflect the day the test was performed or the day the test results were available. The day the test results were available can be influenced by lengthy or uneven turnaround times for the results (eg, backlogs in labs) and can paint a false picture of trends with the virus.

As another example, knowing the percentage of the population that has tested positive for COVID-19 can help inform both resource planning and reopening decisions. But there has been variation in whether counts of positive COVID-19 tests should only include antigen tests, or antibody tests as well. This exact question played out when the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) made decisions that differed from those of many states about whether to include antibody tests in their publicly announced COVID-19 testing numbers,12 perhaps undermining public confidence in the reported data.

MOVING FORWARD WITH STANDARDIZING DEFINITIONS

To capture currently unstandardized metrics with broad applicability, the United States should form a consensus task force to identify and define metrics and, over time, refine them based on current science and public health priorities. The task force would require a mix of individuals with various skill sets, such as expertise in infectious diseases and epidemiology, healthcare operations, statistics, performance measurement, and public health. The US Department of Health and Human Services is likely the appropriate sponsor, with representation from the National Institutes of Health, the CDC, and the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, in partnership with national provider and public health group representatives.

Once standardized definitions for metrics have been agreed upon, the metric definitions will need to be made readily available to the public and healthcare organizations. Standardization will permit collection of electronic health records for quick calculation and review, with an output of dashboards for reporting. It would also prevent every public health and healthcare delivery organization from having to define its own metrics, freeing them up to focus on planning. Several metrics already have standard definitions, and those metrics have proven useful for decision-making. For example, there is agreement that the turnaround time for a SARS-CoV-2 test is measured by the difference in time between when the test was performed and when the test results were available. This standard definition allows for performance comparisons across different laboratories within the same service area and comparisons across different regions of the country. Once the metrics are standardized, public health leaders and healthcare organizations can use variation in performance and outcomes to identify leading indicators for planning.