Language Barriers, Equity, and COVID-19: The Impact of a Novel Spanish Language Care Group

© 2020 Society of Hospital Medicine

Our knowledge of how natural catastrophes affect vulnerable populations should have helped us anticipate how coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) would strike the United States. This disaster has followed the well-heeled path of its predecessors, predictably bending to the influence of social determinants of health,1 structural inequality, and limited access to healthcare. Communities of color were hit early, hit hard,2 and yet again, became our nation’s canary in the coal mine. Hospitals across the country have had a front seat to this novel coronavirus’ disproportionate effect across the diverse communities we serve. Several of the cities and neighborhoods adjacent to our hospital are home to the area’s highest density of limited English proficient (LEP), immigrant, Spanish-speaking individuals.3,4 Our neighbors in these areas are more likely to have lower socioeconomic status, live in crowded housing, work in service industries deemed to be essential, and depend on shared and mass transit to get to work.5,6 As became clear, many in these communities could not work from home, get groceries delivered, or adequately social distance; these were pandemic luxuries afforded to other, more affluent areas.7

THE COVID-19 SURGE

In the weeks between March 25, 2020, and April 13, 2020, the Massachusetts General Hospital in Boston entered a COVID-19 surge now familiar to hospitals across the world. Like our peer institutions, we made broad and creative structural changes to inpatient services to meet the surge and we followed the numbers with anticipation. Over that 2-week period, we indeed saw the COVID-19–positive inpatient population swell as we had feared. However, with each page from the Emergency Department a disturbing trend was borne out:

ADMIT: 53-year-old Spanish-speaker with tachypnea.

ADMIT: 57-year-old factory worker, Spanish-speaking, sick for 10 days, intubated in the ED.

ADMIT: 58-year-old bodega employee, Spanish-speaking, febrile and breathless.

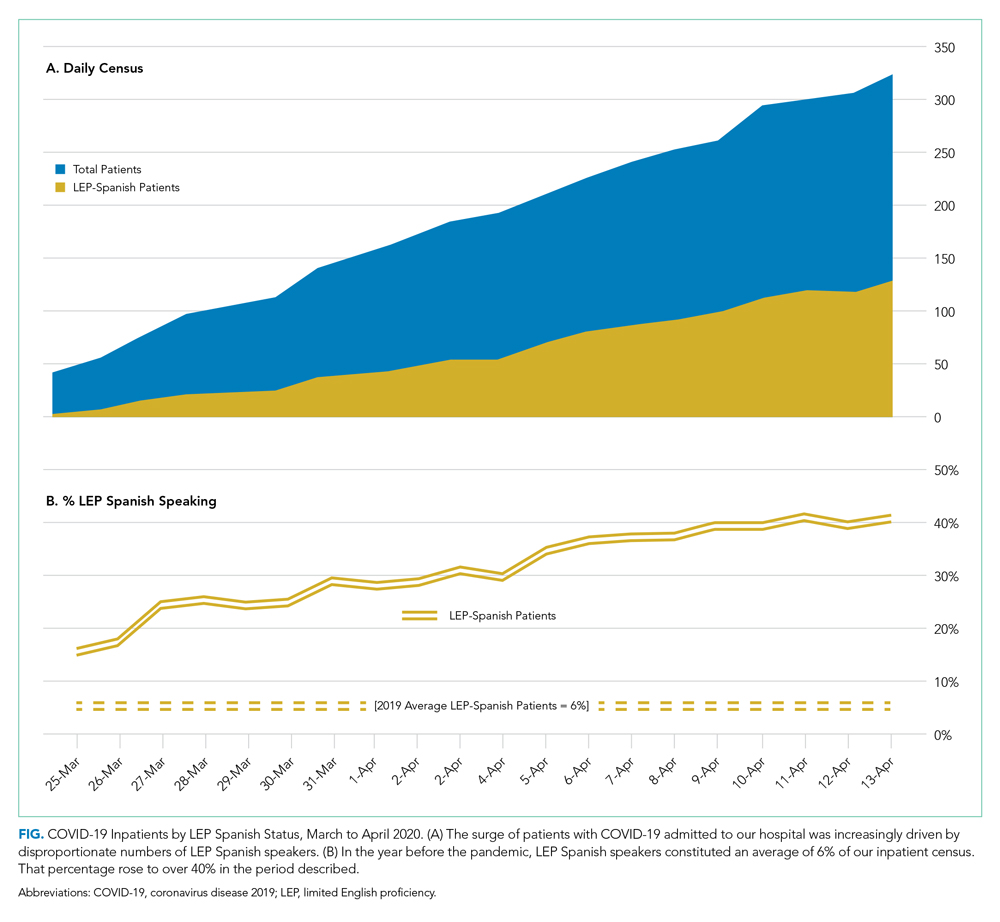

It buzzed across the medical floors and intensive care units: “What is going on in our Spanish speaking neighborhoods?” In fact, our shared anecdotal view was soon confirmed by admission statistics. Over the interval that our total COVID-19 census alarmingly rose sevenfold, the LEP Spanish-speaking census traced a striking curve, increasing nearly 20 times, to constitute over 40% of all COVID-19 patients (Figure). These communities were bearing a disproportionate share of the local burden of the pandemic.

There is consensus in the health care community about the impact of LEP on quality of care, and how, if unaddressed, significant disparities emerge.8 In fact, there is a broadly accepted professional,9 ethical,10 and legal11,12 imperative for hospitals to address the language needs of LEP patients using interpreter services. However, clinicians often feel forced to rely on their own limited language skills to bridge the communication divide, especially in time-limited, critical situations.13 And regrettably, the highly problematic strategy of relying upon family members to aid with communication is still commonly used. The ideal approach, however, is to invest in developing care models that recognize language as an asset and leverage the skills of multilingual clinicians who care for patients in their own language, in a culturally and linguistically competent way.14 It is not surprising that, when clinicians and patients communicate in the same language, there is demonstrably improved adherence to treatment plans,15 increased patient insight into health conditions,16 and improved delivery of health education.17