Gender Distribution in Pediatric Hospital Medicine Leadership

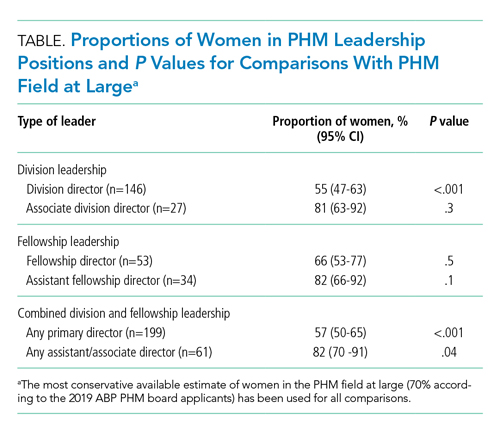

Pediatric Hospital Medicine (PHM), a field early in its development and with a robust pipeline of women, is in a unique position to lead the way in gender equity. We describe the proportion of women in divisional and fellowship leadership positions at university-based PHM programs (n = 142). When compared with the PHM field at large, women appear to be underrepresented as PHM division/program leaders (70% vs 55%; P < .001) but not as fellowship directors (70% vs 66%; P > .05). Women appear proportionally represented in associate/assistant leadership roles when compared with the distribution of the PHM field at large. Tracking these trends over time is essential to advancing the field.

© 2021 Society of Hospital Medicine

Fellowship Leadership

A total of 51 PHM fellowship programs had 53 directors (2 had codirectors), and 66% of the fellowship directors were women (95% CI, 53%-77%). A total of 31 programs had 34 assistant directors (3 programs had 2 assistants), and 82% of the assistant fellowship directors were women (95% CI, 66%-92%).

Comparison With the Field at Large

The inaugural ABP PHM board certification exam in 2019 had 1,627 applicants with 70% women (95% CI, 68%-73%) (Suzanne Woods, MD, email communication, December 4, 2019). The American Academy of Pediatrics Section on Hospital Medicine, the largest PHM-specific organization, has 2,299 practicing physician members with 71% women (95% CI, 69%-73%) (Niccole Alexander, email communication, November 25, 2019). Our random sample of 25% of university-based PHM programs contained 1,063 faculty members with 72% women (95% CI, 69%-75%).

The Table provides P values for comparisons of the proportion of women in each of the above-described leadership roles compared to the most conservative estimate of women in the field from the estimates given above (ie, 70%). Compared with the field at large, women appear to be underrepresented as division directors (70% vs 55%; P < .001) but not as fellowship directors (70% vs 66%; P = .5). There is a higher proportion of women in all associate/assistant director roles, compared with the population (82% vs 70%; P = .04).

DISCUSSION

We found a significant difference between the proportion of women as PHM division directors (55%) when compared with the proportion of women physicians in PHM (70%), which suggests that women are underrepresented in clinical leadership at university-based pediatric hospitalist programs. Similar findings are described in other specialties, including notably adult hospital medicine.4 Burden et al found that only 16% of hospital medicine program leaders were women despite an equal number of women and men in the field. PHM has a much larger proportion of women, compared with that of hospital medicine, and yet women are still underrepresented as program leaders.

We found no disparities between the proportion of women as PHM fellowship directors and the field at large. These results are similar to those of other studies, which showed a higher number of women in educational leadership roles and lower representation in roles with influence over policy and allocation of resources.13,14 Although the proportion of women in educational roles itself is not a concern, there is evidence that these positions may be undervalued by some institutions, which provide these positions with lower salaries and fewer opportunities for career advancement.13,14

Interestingly, women are well-represented in associate/assistant director roles at both the division and fellowship leader level when comparing the distribution in those roles with that of the PHM field at large. This finding suggests that the pipeline of women is robust and potentially may indicate positive change. Alternatively, this finding may reflect a previously described phenomenon of the “sticky floor” in which women are “stuck” in these supportive roles and do not necessarily advance to higher-impact positions.15 We found a statistically significant higher proportion of women in the combined group of all associate/assistant directors compared with the overall population, which raises the concern that supportive leadership roles may represent “women’s work.”16 Future studies are needed to track whether these women truly advance or whether women are overrepresented in supportive leadership positions at the expense of primary leadership positions.

Adequate representation of women alone is not sufficient to achieve gender equity in medicine. We need to understand why there is a lower representation of women in leadership positions. Some barriers have already been described, including gender bias in promotions,17 higher demands outside of work,18 and lower pay,3 though none are specific to PHM. A further qualitative exploration of PHM leadership would help describe any barriers women in PHM specifically may be facing in their career trajectory. In addition, more information is needed to explore the experience of women with intersectional identities in PHM, especially since they may experience increased bias and discrimination.19

Limitations of this study include the lack of a centralized list of PHM programs and data on PHM workforce. Our three estimates for the proportion of women in PHM were similar at 70%-71%; however, these are only proxies for the true gender distribution of PHM physicians, which is unknown. PHM leadership targets of close to 70% women would be reflective of the field at large; however, institutional variation may exist, and ideally leadership should be diverse and reflective of its faculty members. Our study only describes university-based PHM programs and, therefore, is not necessarily generalizable to nonuniversity programs. Further studies are needed to evaluate any potential differences based on program type. In our study, gender was used in binary terms; however, we acknowledge that gender exists on a spectrum.