Finding the Value in Personal Protective Equipment for Hospitalized Patients During a Pandemic and Beyond

© 2020 Society of Hospital Medicine

Due to the pandemic spread of the severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2), the cause of COVID-19 infection, there is significant disruption to the global supply of PPE.2 Order volumes of PPE have increased, prices have surged, and distributors are experiencing challenges meeting order demands.3 With decreased overseas exports, suppliers have placed hospitals on PPE allocations, and many hospitals’ orders for PPE have been only partially filled.3,4 Unless hospitals have established stockpiles, most only have supplies for 3-7 days of routine use, leaving them vulnerable to exhausting PPE supplies. At the onset of the pandemic, 86% of United States hospitals reported concerns about their PPE supply.4

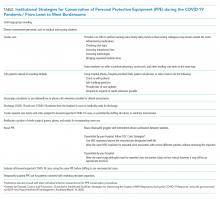

The potential for PPE shortages has led both the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) and the World Health Organization to call for the rational and appropriate use of PPE in order to conserve supplies.2,3 By the time COVID-19 was declared a pandemic, 54% of hospitals had imposed PPE conservation protocols,4 with more expected to follow in the weeks and months to come. Innovative protocols have been conceptualized and used to conserve PPE in hospitals (Table).

Yet these conservation protocols often fail to identify missed opportunities to improve the value of PPE that already exist in hospital care. By defining the value of inpatient PPE, hospitals can identify opportunities for value improvement. Changes implemented now will maximize PPE value and preserve supply during this pandemic and beyond.

THE VALUE OF PPE

In order to conserve PPE supply, hospitals might consider limiting PPE to cases in which clear evidence exists to support its use. However, evidence for PPE use can be challenging to interpret because the impact of preventing nosocomial infections (an outcome that did not occur) is inherently problematic to measure. This makes assessing the value of PPE in preventing nosocomial transmission in specific situations difficult.

The basis of using PPE is its effectiveness in controlling outbreaks.1 A meta-analysis of 6 case-control studies from the SARS outbreak of 2003, which disproportionately infected healthcare workers, suggested that handwashing and PPE were effective in preventing disease transmission. Handwashing alone reduced transmission by 55%, wearing gloves by 57%, and wearing facemasks by 68%; the cumulative effect of handwashing, masks, gloves, and gowns reduced transmission by 91%.5 A cohort study of healthcare workers exposed to H1N1 influenza A in 2009 found that use of a facemask or an N95 respirator was associated with negative viral serology suggesting noninfected status.6 With respiratory syncytial virus (RSV) outbreaks, a narrative synthesis of 4 studies examining transmission also suggested gowns, facemasks, and eye protection are effective, with eye protection perhaps more effective than gowns and masks.7 Yet these studies’ conclusions are limited by study design differences and small sample sizes.

The evidence supporting PPE use for routine hospital conditions is more challenging to interpret. One pediatric study of seasonal respiratory viruses showed that adding droplet precautions to an existing policy of contact precautions alone decreased nosocomial infections for most viruses evaluated.8 Yet this study, like many of PPE use, is limited by sample size and possible misclassification of exposure and outcome biases. Because PPE is always utilized in conjunction with other preventive measures, isolating the impact of PPE is challenging, let alone isolating the individual effects of PPE components. In the absence of strong empirical evidence, hospitals must rely on the inherent rationale of PPE use for patient and healthcare worker safety in assessing its value.

In order to protect patients from disease transmission during a pandemic, hospitals might also reconsider whether to use PPE in cases in which evidence is absent, such as routine prevention for colonized but noninfected patients. However, evidence of the possible patient harms of PPE are emerging. Healthcare providers spend less time with isolated patients9,10 and document fewer vital signs.11 Patients in PPE may experience delays in admission12 and discharge,13 and have higher rates of falls, pressure ulcers, and medication errors.14,15 They may also experience higher rates of anxiety and depression.16 Yet no evidence suggests PPE use for noninfected patients prevents transmission to patients or to healthcare workers. Using PPE when it is not indicated deemphasizes the value of other preventative precautions (eg, handwashing), unnecessarily depletes PPE supply, and may create patient harm without added benefit. High-value PPE, both during a pandemic and beyond, is defined by a system designed so that healthcare workers use PPE when they need it, and do not use PPE when not indicated.