Factors Associated with Differential Readmission Diagnoses Following Acute Exacerbations of Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease

BACKGROUND: Readmissions after exacerbations of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) are penalized under the Hospital Readmissions Reduction Program (HRRP). Understanding attributable diagnoses at readmission would improve readmission reduction strategies.

OBJECTIVES: Determine factors that portend 30-day readmissions attributable to COPD versus non-COPD diagnoses among patients discharged following COPD exacerbations.

DESIGN, SETTING, AND PARTICIPANTS: We analyzed COPD discharges in the Nationwide Readmissions Database from 2010 to 2016 using inclusion and readmission definitions in HRRP.

MAIN OUTCOMES AND MEASURES: We evaluated readmission odds for COPD versus non-COPD returns using a multilevel, multinomial logistic regression model. Patient-level covariates included age, sex, community characteristics, payer, discharge disposition, and Elixhauser Comorbidity Index. Hospital-level covariates included hospital ownership, teaching status, volume of annual discharges, and proportion of Medicaid patients.

RESULTS: Of 1,622,983 (a weighted effective sample of 3,743,164) eligible COPD hospitalizations, 17.25% were readmitted within 30 days (7.69% for COPD and 9.56% for other diagnoses). Sepsis, heart failure, and respiratory infections were the most common non-COPD return diagnoses. Patients readmitted for COPD were younger with fewer comorbidities than patients readmitted for non-COPD. COPD returns were more prevalent the first two days after discharge than non-COPD returns. Comorbidity was a stronger driver for non-COPD (odds ratio [OR] 1.19) than COPD (OR 1.04) readmissions.

CONCLUSION: Thirty-day readmissions following COPD exacerbations are common, and 55% of them are attributable to non-COPD diagnoses at the time of return. Higher burden of comorbidity is observed among non-COPD than COPD rehospitalizations. Readmission reduction efforts should focus intensively on factors beyond COPD disease management to reduce readmissions considerably by aggressively attempting to mitigate comorbid conditions.

© 2020 Society of Hospital Medicine

Sensitivity Analyses and Missing Data

We conducted sensitivity analyses to determine whether a lower age cutoff (≥18 years) affects modeling. We also tested the stability of our estimates across each individual year of the pooled analysis. To test the effect of time to differential readmission, we fit a Cox proportional hazards model within the readmitted patient subgroup with Huber-White standard errors clustered at the hospital level to estimate the differential hazard of readmission for COPD versus non-COPD diagnoses across the same variables of interest as a sensitivity analysis. We also tested using a liberal classification of readmission diagnoses by sorting into “respiratory” versus “nonrespiratory” returns, with DRGs 163 through 208 for “respiratory” versus all others, respectively. We tested the agreement between the HRRP ICD-based classification and DRG classification using Cohen’s kappa.

We designated a threshold of 10% missing data to necessitate imputation techniques, determined a priori for our main variables, none of which met this level. Complete case analyses were used for all models. Analyses were performed in Stata version 15.1 (StataCorp, College Station, Texas) with weighted estimates reported using patient-level survey weights for national representativeness.37 The study protocol was reviewed by the institutional review board at the University of California, Los Angeles, and deemed exempt from oversight due to the publicly available, deidentified nature of the data (IRB# 18-001208).

RESULTS

Out of 104,897,595 hospitalizations in the NRD, a final sample of 1,622,983 COPD discharges was identified for our analysis (sample weighted effective population 3,743,164). The overall readmission rate was 17.25%, with 7.69% of patients readmitted for COPD and 9.56% readmitted for other diagnoses. Those with COPD readmissions were significantly younger with a lower proportion of Medicare and a higher proportion of Medicaid as the primary payer compared with those readmitted for all other causes (Table 1). Compared with non-COPD-readmitted patients, COPD-readmitted patients were more frequently discharged home without services and had shorter lengths of stay. Noninvasive ventilation was more common among COPD readmissions while mechanical ventilation and tracheostomy placement were less frequent compared with non-COPD readmissions. Compared with non-COPD-readmitted patients, COPD-readmitted patients had significantly lower mean Elixhauser Comorbidity Index scores (17.8 vs 22.8), rates of congestive heart failure (28.3% vs 38.6%), and renal failure (11.8% vs 21.5%; Appendix Table 3).

Readmission rates were significantly higher for non-COPD causes than for COPD causes across all hospital types by ownership, teaching status, or size (Table 2). Parallel patterns were observed for non-COPD and COPD readmissions across hospital types, with two key exceptions. Across categories of hospital ownership, for-profit hospitals had the highest rates for non-COPD readmissions, with no differences in hospital control for COPD rehospitalizations. While rates did not vary for non-COPD readmissions by within-hospital Medicaid prevalence, COPD readmission rates significantly increased as Medicaid-paid patient-days increased within hospitals.

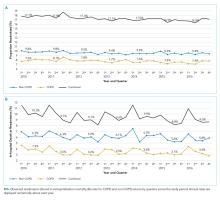

The median time to non-COPD readmission was 13 days, whereas COPD readmission was 14 days. More COPD readmissions occurred in the first 2.4 days after discharge, after which the proportion of non-COPD cases readmitted consistently increased. Observed readmission rates for COPD and other diagnoses trended down over the study period (Figure 1A), as did mortality rates during readmission stays (Figure 1B). Sepsis, heart failure, and respiratory infections were seven of the top 10 ranked DRGs for the non-COPD rehospitalizations (Appendix Table 4). In trend analyses (Appendix Tables 5-8), sepsis and DRGs with major comorbidities increased in proportion each year across the study period, possibly reflecting changes in coding practices.38

In our adjusted multinomial logistic regression model (Table 3), where the outcomes were not readmitted (reference category) versus readmitted for non-COPD diagnosis or for qualifying COPD diagnosis, the effect size of comorbidity, operationalized by change in the Elixhauser Comorbidity Index, was larger for non-COPD than non-COPD readmissions (odds ratio [OR] 1.19 vs 1.04 per one-half standard deviation of Elixhauser Index, an approximately 7.5 unit change in score). Increases in age were associated with higher non-COPD readmissions (OR 1.06 per 10 years) while actually protective against COPD readmissions (OR 0.89 per 10 years). Compared with Medicare patients, Medicaid patients had higher odds of COPD readmission (OR 1.10 vs 1.03) while the converse was observed in the privately insured (OR 0.65 vs 0.76). Transfers to postacute care facilities, referenced against discharges home, had a larger association with readmissions for non-COPD causes (OR 1.35 vs 1.00), whereas home-health had nearly equal adjusted readmission odds for each outcome (1.31 vs 1.30). Length of stay was associated with 1% greater odds per day for readmission for non-COPD causes than COPD returns. Regarding in-hospital events, odds of COPD readmission were higher for noninvasive ventilation (OR 1.37 vs 0.89) and mechanical ventilation (OR 0.87 vs 0.79, Appendix Table 9), which should be interpreted in the context that analyses were restricted to those discharged alive from their index admission, possibly biasing the true effect estimates due to competing risk of index in-hospital mortality.

In sensitivity analyses, we found no significant differences between our Cox proportional hazards model (Appendix Table 10) and our multinomial model. When we liberalized readmission outcome definitions to respiratory versus nonrespiratory DRGs, we observed 86% agreement between the HRRP and DRG classification systems (κ = 0.73, P < .001). Among the discordant observations, 13% of non-COPD readmissions under HRRP criteria were reclassified as respiratory by DRG and 1% of COPD readmissions under HRRP reclassified as nonrespiratory. When our multinomial model (Appendix Table 11) was re-fit using the DRG-based outcome, only slight changes in effect size occurred. For the Elixhauser Index, the OR for COPD by HRRP was slightly lower than that for respiratory DRGs (1.04 vs 1.05), parallel with the difference between non-COPD by HRRP and nonrespiratory DRG classification (1.19 vs 1.21, respectively). This result underscores the greater influence of comorbidity on non-COPD than COPD readmissions. Only one sign change was observed in those who underwent tracheostomy (OR 0.91 for “nonrespiratory” DRG vs 1.07 for “non-COPD” by HRRP), likely reflecting the shift of some non-COPD diagnoses into the respiratory categorization based on tracheostomy having its own DRG. We also evaluated the multinomial model without the Elixhauser Index (only covariates) and found minor adjustments to the effect sizes of the covariates, particularly for discharge disposition. However, no sign changes were observed for any of the odds ratios (Appendix Table 12). Readmission odds by the Elixhauser score for each condition were stable across years (Appendix Figure 2 & Appendix Table 13). Finally, including 18-39-year-old patients in the cohort did not substantially change our estimates (Appendix Table 14).