Things We Do for No Reason™: Routine Thyroid-Stimulating Hormone Testing in the Hospital

© 2020 Society of Hospital Medicine

HARMS ASSOCIATED WITH ROUTINE TSH TESTING

NTIS may cause TSH, T4, and even FT4 to increase or decrease, even in discordant patterns, such as in the case above. This makes interpretation difficult for the hospitalist, who may wonder

WHEN TO CONSIDER TSH TESTING

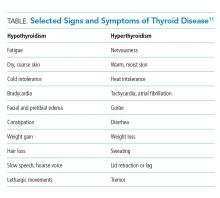

Given the limitations of TSH testing in hospitalized patients due to NTIS, the AACE/ATA recommend TSH measurement in hospitalized patients only in cases of high clinical suspicion for thyroid dysfunction (Grade A, Best Level Evidence 2).19 The specificity of TSH testing in the hospital setting is too low to justify screening for mild or subclinical disease.8 Instead, directed thyroid function testing should be performed for hospitalized patients with sufficient signs and symptoms to raise the pretest probability of a clinically relevant result (Table). According to Attia et al., the total number of signs and symptoms (rather than one particular sign or symptom) may be the most reliable indicator. In two outpatient studies (no inpatient data available), the presence of one to two signs or symptoms of thyroid disease yielded an LR+ of 0.11-0.2, three to four signs or symptoms yielded an LR+ of 0.74-1.14, and five or more signs or symptoms yielded an LR+ of 6.75-18.6.11 For example, if a general medical patient (prevalence of undiagnosed hypothyroidism estimated to be 0.6%) has constipation and fatigue (LR+ 0.2), then the pretest probability would be approximately 0.1%. If the TSH level results between 6.7 and 20 mIU/L (LR+ 0.74), the posttest probability of thyroid disease would remain only 0.1%. Alternatively, a general medical patient with five symptoms consistent with hypothyroidism (LR+ 18.6) would have a pretest probability of 10%. If the TSH level results >20 mIU/L (LR+ 11.1), then the posttest probability of hypothyroidism would be 55%.11

For patients on stable doses of thyroid hormone replacement, although it may seem logical to check a TSH level upon admission to the hospital, guidelines recommend monitoring levels routinely in the outpatient setting, at most once every 12 months. More frequent monitoring should be undertaken only if clinical symptoms suggest that a dose change may be needed,19 and routine hospital testing should be avoided because of the potential for misleading results.

However, in some specific clinical scenarios, it may be reasonable to test for thyroid disease. Guidelines suggest TSH testing in the evaluation of certain conditions such as atrial fibrillation20 and syndrome of inappropriate antidiuretic hormone (SIADH).21 In addition, in the evaluation of unexplained sinus tachycardia, it is reasonable to test for hyperthyroidism after more common causes (pain, anxiety, infection, anemia, drug ingestion, and beta-blocker withdrawal) have been excluded.22 In the evaluation of delirium, TSH may be an appropriate “second tier” test after more likely contributors have been excluded.23