A Plea to Reconsider the Diagnosis

© 2019 Society of Hospital Medicine

The main objective information added here is that the patient now has his second episode of likely aseptic meningitis with neutrophilic predominance, although it is possible that antibiotic therapy may have led to a false-negative CSF culture. However, this possible partial treatment was not a consideration in the first episode of meningitis. Having two similar episodes increases the likelihood that the patient has an underlying inflammatory/immune disorder, likely genetic (now termed “inborn errors of immunity”), or that there is a common exposure not yet revealed in the history (eg, drug-induced meningitis). Primary immunodeficiency is less likely than an autoinflammatory disease, considering the patient’s course of recovery with the first episode.

Further evaluation of the CSF did not reveal a pathogen. Bacterial CSF culture was sterile, and PCRs for HSV and enterovirus were negative.

The differential diagnosis is narrowing to include causes of recurrent, aseptic, neutrophilic meningitis. The incongruous head circumference and weight could be due to a relatively large head, a relatively low weight, or both. To interpret these data properly, one also needs to know the patient’s length, the trajectory of his growth parameters over time, and the parents’ heights and head circumferences. One possible scenario, considering the rest of the history, is that the patient has a chronic inflammatory condition of the central nervous system (CNS), leading to hydrocephalus and macrocephaly. It is possible that systemic inflammation could also lead to poor weight gain.

When considering chronic causes of aseptic meningitis associated with neutrophil predominance in the CSF, autoinflammatory disorders (cryopyrin-associated periodic syndrome, Muckle–Wells syndrome, neonatal-onset multisystem inflammatory disease [NOMID], and chronic infantile neurological cutaneous articular syndrome [CINCA]) should be considered. The patient lacks the typical deforming arthropathy of the most severe NOMID/CINCA phenotype. If the brain imaging does not reveal another etiology, then genetic testing of the patient is indicated.

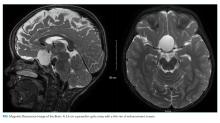

Because of the history of recurrent meningitis with marked neutrophilic pleocytosis, yet no evidence of infection given normal glucose, only mildly elevated protein, and no culture growth, an MRI of the brain was obtained. MRI revealed a sharply circumscribed, homogeneous, nonenhancing 2.6 cm diameter cystic suprasellar mass with a thin rim of capsular enhancement (Figure). The appearance was most consistent with an epidermoid cyst, a dermoid, Rathke’s cleft cyst (RCC), or, less likely, a craniopharyngioma. The recurrent aseptic meningitis was attributed to chemical meningitis secondary to episodic discharging of the tumor. There was no hydrocephalus on imaging, and the enlarged head circumference was attributed to large parental head circumference.

Antibiotics were discontinued and supportive care continued. A CSF cholesterol level of 4 mg/dL was found (normal range 0.6 ± 0.2 mg/dL) on the CSF from admission. Fevers and symptoms ultimately improved with 72 hours of admission. He was discharged with neurosurgical follow-up, and within a year, he developed a third episode of aseptic meningitis. He eventually underwent a craniotomy with near-total resection of the cyst. Histopathological analysis indicated the presence of an underlying RCC, despite initial clinical and radiographic suspicion of an epidermoid cyst. He recovered well with follow-up imaging demonstrating stable resolution of the RCC and no further incidents of aseptic meningitis in the 12 months since the surgery.