Utility of ICD Codes for Stress Cardiomyopathy in Hospital Administrative Databases: What Do They Signify?

Prior studies of stress cardiomyopathy (SCM) have used International Classification of Diseases (ICD) codes to identify patients in administrative databases without evaluating the validity of these codes. Between 2010 and 2016, we identified 592 patients discharged with a first known principal or secondary ICD code for SCM in our medical system. On chart review, 580 charts had a diagnosis of SCM (positive predictive value 98%; 95% CI: 96.4-98.8), although 38 (6.4%) did not have active clinical manifestations of SCM during the hospitalization. Moreover, only 66.8% underwent cardiac catheterization and 91.5% underwent echocardiography. These findings suggest that, although all but a few hospitalized patients with an ICD code for SCM had a diagnosis of SCM, some of these were chronic cases, and numerous patients with a new diagnosis of SCM did not undergo a complete diagnostic workup. Researchers should be mindful of these limitations in future studies involving administrative databases.

© 2020 Society of Hospital Medicine

RESULTS

During 2010-2016, a total of 592 patients with a first known ICD code in our EHR for SCM were hospitalized, comprising 242 (41.0%) with a principal diagnosis code. Upon chart review, we were unable to confirm a clinical diagnosis of SCM among 12 (2.0%) patients. In addition, 38 (6.4%) were chronic cases of SCM, without evidence of active disease at the time of hospitalization. In general, chronic cases typically carried an SCM diagnosis from a hospitalization at a non-Baystate hospital (outside our EHR), or from an outpatient setting. Occasionally, we also found cases where the diagnosis of SCM was mentioned but testing was not pursued, and the patient had no symptoms that were attributed to SCM. Overall use of echocardiogram and cardiac angiography was 91.5% and 66.8%, respectively, and was lower in chronic than in new cases of SCM.

Compared with patients with a secondary diagnosis code, patients with a principal diagnosis of SCM underwent more cardiac angiography and echocardiography (Table 1). When comparing the difference between those with principal and secondary ICD codes, we found that 237 (98%) vs 305 (87%) were new cases of SCM, respectively, and all 12 patients without any clinical diagnosis of SCM had been given a secondary ICD code. Between 2010 and 2016, we noted a significant increase in the number of cases of SCM (Cochrane–Armitage, P < .0001).

The overall PPV (95% CI) of either principal or secondary ICD codes for any form or presentation of SCM was 98.0% (96.4-98.8) with no difference in PPV between the coding systems (ICD-9, 66% of cases, PPV 98% [96.0-99.0] vs ICD-10, PPV 98% [94.9-99.2; P = .98]). Because all patients without a diagnosis of SCM were given secondary ICD codes, this changed the PPV (95% CI) for principal and secondary SCM to 100% (98.4-100.0) and 96.6% (94.1-98.0), respectively. When chronic cases were included as noncases, the PPV (95% CI) to detect a new case of SCM decreased to 97.9% (95.2-99.1) and 87.1% (83.0-90.2) for principal and secondary SCM, respectively (Table 1).

DISCUSSION

In this study, we found a strong relationship between the receipt of an ICD code for SCM and the clinical documentation of a diagnosis of SCM, with an overall PPV of 98%. The PPV was higher when the sample was limited to those assigned a principal ICD code for SCM, but it was lower when considering that some ICD codes represented chronic SCM from prior hospitalizations, despite our attempts to exclude these cases administratively prior to chart review. Furthermore, cardiac catheterization and echocardiography were used inconsistently and were less frequent among secondary compared with a principal diagnosis of SCM. Thus, although a principal ICD diagnosis code for SCM appears to accurately reflect a diagnosis of SCM, a secondary code for SCM appears less reliable. These findings suggest that future epidemiological studies can rely on principal diagnosis codes for use in research studies, but that they should use caution when including patients with secondary codes for SCM.

Our study makes an important contribution to the literature because it quantitates the reliability of ICD codes to identify patients with SCM. This finding is important because multiple studies have used this code to study trends in the incidence of this disease,1-8 and futures studies will almost certainly continue to do so. Our results also showed similar demographics and trends in the incidence of SCM compared with those of prior studies1-3,11 but additionally revealed that these codes also have some important limitations.

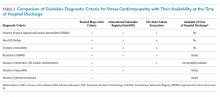

A key factor to remember is that neither a clinical diagnosis nor an ICD code at the time of hospital discharge is based upon formal diagnostic criteria for SCM. Importantly, all currently proposed diagnostic criteria require resolution of typical regional wall motion abnormalities before finalizing a research-grade diagnosis of SCM (Table 2).12,13 However, because the median time to recovery of ejection fraction in SCM is between three and four weeks after hospital discharge (with some recovery extending much longer),6 it is almost impossible to make a research-grade diagnosis of SCM after a three- to four-day hospitalization. Moreover, 33% of our patients did not undergo cardiac catheterization, 8.5% did not undergo echocardiography, and it is our experience that testing for pheochromocytoma and myocarditis is rarely done. Thus, we emphasize that ICD codes for SCM assigned at the time of hospital discharge represent a clinical diagnosis of SCM and not research-grade criteria for this disease. This is a significant limitation of prior epidemiologic studies that consider only the short time frame of hospitalization.

A limitation of our study is that we did not attempt to measure sensitivity, specificity, or the negative predictive value of these codes. This is because measurement of these diagnostic features would require sampling some of our hospital’s 53,000 annual hospital admissions to find cases where SCM was present but not recognized. This did not seem practical, particularly because it might also require directly overreading imaging studies. Moreover, we believe that for the purposes of future epidemiology research, the PPV is the most important feature of these codes because a high PPV indicates that when a principal ICD code is present, it almost always represents a new case of SCM. Other limitations include this being a single-center study; the rates of echocardiograms, cardiac angiography, clinical diagnosis, and coding may differ at other institutions.

In conclusion, we found a high PPV of ICD codes for SCM, particularly among patients with a principal discharge diagnosis of SCM. However, we also found that approximately 8% of cases were either wrongly coded or were chronic cases. Moreover, because of the need to document resolution of wall motion abnormalities, essentially no patients met the research-grade diagnostic criteria at the time of hospital discharge. Although this increases our confidence in the results of past studies, it also provides some caution to researchers who may use these codes in the future.