Improving Resident Feedback on Diagnostic Reasoning after Handovers: The LOOP Project

Appropriate calibration of clinical reasoning is critical to becoming a competent physician. Lack of follow-up after transitions of care can present a barrier to calibration. This study aimed to implement structured feedback about clinical reasoning for residents performing overnight admissions, measure the frequency of diagnostic changes, and determine how feedback impacts learners’ self-efficacy. Trainees shared feedback via a structured form within their electronic health record’s secure messaging system. Forms were analyzed for diagnostic changes. Surveys evaluated comfort with sharing feedback, self-efficacy in identifying and mitigating cognitive biases’ negative effects, and perceived educational value of night admissions—all of which improved after implementation. Analysis of 544 forms revealed a 43.7% diagnostic change rate spanning the transition from night-shift to day-shift providers; of the changes made, 29% (12.7% of cases overall) were major changes. This study suggests that structured feedback on clinical reasoning for overnight admissions is a promising approach to improve residents’ diagnostic calibration, particularly given how often diagnostic changes occur.

© 2019 Society of Hospital Medicine

The intervention entailed residents delivering structured feedback to their colleagues regarding their patients’ diagnoses after transitions of care. The predominant setting was the inpatient hospital medicine day-shift team providing feedback to the night-shift team regarding overnight admissions. Feedback about patients (usually chosen by the day-shift team) was delivered through completion of a standard templated form (Figure) usually sent within 24 hours after hospital admission through secure messaging (ie, EPIC In-Basket message utilizing a Smartphrase of the LOOP feedback form). A 24-hour time period was chosen to allow for rapid cycling of feedback focusing on initial diagnostic assessment. Site leads and resident champions promoted the project through presentations, informal discussions, and prizes for high completion rates of forms and surveys (ie, coffee cards and pizza).

Feedback forms were collected by site leads. A categorization rubric was developed during a pilot phase. Diagnoses before and after the transition of care were categorized as no change, diagnostic refinement (ie, the initial diagnosis was modified to be more specific), disease evolution (ie, the patient’s physiology or disease course changed), or major diagnostic change (ie, the initial and subsequent diagnoses differed substantially). Site leads acted as single-coders and conference calls were held to discuss coding and build consensus regarding the taxonomy. Diagnoses were not labeled as “right” or “wrong”; instead, categorization focused on differences between diagnoses before and after transitions of care.

Residents were invited to complete surveys before and after the rotation during which they had the opportunity to give or receive feedback. A unique identifier was entered by each participant to allow pairing of pre- and postsurveys. The survey (Appendix 1) was developed and refined during the initial pilot phase at the University of Minnesota. Surveys were collected using RedCap and analyzed using SAS version 9.3 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, North Carolina). Differences between pre- and postsurveys were calculated using paired t-tests for continuous variables, and descriptive statistics were used for demographic and other items. Only surveys completed by individuals who completed both pre- and postsurveys were included in the analysis.

RESULTS

Overall, there were 716 current residents in the training programs that participated in this study; one site planned on participating but did not complete any forms. A total of 405 residents were eligible to participate during the study period. Overall, 221 (54.5%)

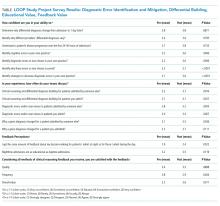

Survey results (Table) indicated significantly improved self-efficacy in identifying cognitive errors in residents’ own practice, identifying why those errors occurred, and identifying strategies to decrease future diagnostic errors. Participants noted increased frequency of discussions within teams regarding differential diagnoses, diagnostic errors, and why diagnoses changed over time. The feedback process was viewed positively by participants, who were also generally satisfied with the overall quality, frequency, and value of the feedback received. After the intervention, participants reported an increase in the amount of feedback received for night admissions and an overall increase in the perception that nighttime admissions were as “educational” as daytime admissions.

Of 544 collected forms, 238 (43.7%) showed some diagnostic change. These changes were further categorized into disease evolution (60 forms, 11.0%), diagnostic refinement (109 forms, 20.0%), and major diagnostic change (69 forms, 12.7%).